Interactive: How corporate giving changed among the world’s top brands

A car stops at an empty house on a Detroit street. Three passengers get out and approach the house, snapping pictures of different details that need renovation. They return to the car and then repeat the process at the next house. The passengers aren’t snooping neighbors. They’re Detroit residents who are knee deep in a data gathering initiative called The Motor City Mapping Project, led by Loveland Technologies.

A car stops at an empty house on a Detroit street. Three passengers get out and approach the house, snapping pictures of different details that need renovation. They return to the car and then repeat the process at the next house. The passengers aren’t snooping neighbors. They’re Detroit residents who are knee deep in a data gathering initiative called The Motor City Mapping Project, led by Loveland Technologies.

Loveland Technologies is a software company solving urban development problems using interactive mapping and crowdsourcing. With these technologies Loveland is focusing on solving the issue of blight in a new way. “Applying a startup mentality to solving Detroit’s challenges means taking the best of the rapid-fire ‘innovate-test-iterate’ cycle and bridging it with a vision for creating long-term change,” says Jerry Paffendorf, the company’s CEO and co-founder. This vision would be difficult to execute, though, without support from a new kind of corporate philanthropy partnership. “JPMorgan Chase provides that kind of bridge: patient capital for innovative solutions to deep problems.”

The concept of private companies donating data and analytical skills emerged on the global scene at the 2011 World Economic Forum in Davos, where attendees concluded that corporations with troves of data should know more about the benefits of sharing that data for public good. Since then, the United Nations Global Pulse initiative has promoted the model as a way to both spark innovation and address public interest issues across the globe. Insights from corporate-funded studies or the donation of proprietary data can be used to address challenges from disease outbreaks to economic stressors to fallout from natural disasters. The UN, for example, has accumulated data studies on macroeconomic issues in Cambodia, Ugandan community radio, and social attitudes toward biofuels.

As evidenced by Motor City Mapping, data can make a profound difference at the hyper-local level too, particularly in finding solutions to issues like urban blight and unemployment. In Detroit, JPMorgan Chase donated data and analytics resources that are contributing to economic rebuilding efforts, closing the skills gap, and informing urban planning. It’s part of a broader effort by JPMorgan Chase to take a data-driven approach and use the firm’s talent and resources to make a lasting impact on the communities it works with.

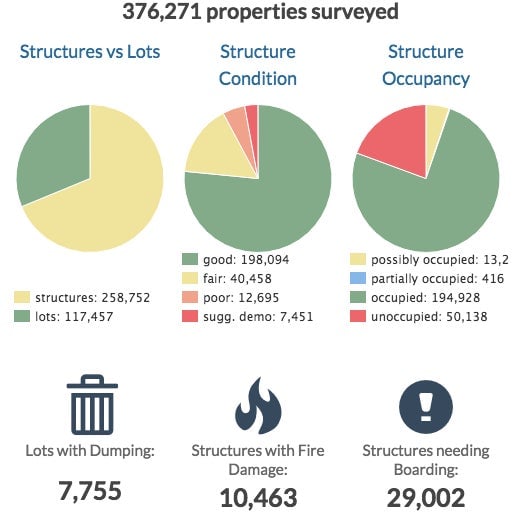

As a funder and partner to Motor City Mapping, JPMorgan Chase is helping ensure that the work of the photo-snapping volunteers—who have surveyed 380,000 parcels to date—has the maximum effect. The information has now been digitized, thanks to support from the company and Data Driven Detroit. The result is a fascinating interactive map of the city that shows the number of structures versus vacant lots, the condition of those structures (whether they’ve been affected by fire or illegal dumping), and their occupancy status. The map is visible on a house-by-house level—users can search an address and see a photo of what it looks like—and individual residents can contribute their own photos to keep the map updated. Data from the project provided the backbone for a report produced by the Detroit Blight Removal Task Force, an organization that has a goal of removing every blighted vacant structure in the city.

As the world recognizes the full power of data, it’s emerged as a key aspect of a new corporate responsibility model that combines various capabilities to do the most good. Instead of handing over a check and calling it a day, corporate responsibility has evolved to be more strategic and multi-faceted in its approach.

JPMorgan Chase is at the forefront of this new holistic approach, pioneering a model that offers a mix of money, employee expertise, and data with the belief that the same things that contribute to business success should also shape the way companies think about solving problems in civil society.

A recent two-part report (pdf) published by the company in partnership with the Corporation for a Skilled Workforce presents data from the US Census and job postings to identify specific opportunities in Detroit’s job market. Part of what it revealed was that Detroit’s employment issue isn’t a lack of jobs; it’s that the skills of the unemployed don’t align with open positions. This skills gap is of particular concern for middle-skill jobs—or jobs that require a high school diploma and technical training. Among Detroit residents, 22% lack a high school diploma or GED.

Whereas in the past a strategy for getting those diplomas in-hand might have been dictated by history or hunches, today’s data-based approach helps organizations optimize their resources and efforts. The aforementioned report has already informed several initiatives to address the skills gap in the city: its identification of the most desirable skills helped the mayor’s Detroit Workforce Development Board train more than 3,800 Detroit residents with in-demand skills and ultimately contributed to adding 8,000 more Detroiters to the workforce in 2016.

It also prompted the creation of the Detroit Workforce System Leadership Academy, a year-long program that joins 22 of the city’s most prominent established businesspeople to solve universal employment issues. Mayor Mike Duggan praised the report as “giving us an invaluable tool in supporting our new Workforce Development Board as it tackles the challenges ahead.”

And the value of the data provided by the Motor City Mappers has already proven persuasive enough to inspire spin-offs in Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus. The data-driven approach is spreading to the places that need it most, and, increasingly, businesses are recognizing that their philanthropic efforts can offer more than money alone.

Businesses across the country are recognizing data-driven initiatives as prime opportunities to contribute to effective, localized, and measurable change. House by house, person by person, data can help transform a city.

This article was produced on behalf of JPMorgan Chase by Quartz Creative and not by the Quartz editorial staff.