Solar-eclipse fever means counterfeit glasses are flooding Amazon’s market

One reason a total solar eclipse is so compelling is that it’s the one time humans can turn their soft, sensitive eyes to the sky and gaze directly upon the celestial body that gives life to us and everything else on Earth.

One reason a total solar eclipse is so compelling is that it’s the one time humans can turn their soft, sensitive eyes to the sky and gaze directly upon the celestial body that gives life to us and everything else on Earth.

But that’s only for two minutes or so, and only for the people who will be in the so-called “path of totality” that cuts across the US. In the time leading up to and following those few moments on August 21, and for everyone else in the US, there will be many more minutes of partial eclipse, which require specialized, ultra-dark glasses to see safely.

As August 21 nears, eclipse-chasers are realizing that if they want to see the sun disappear behind the moon, they can’t just wake up on the day of the astronomical event and step outside their homes. They’ll need solar eclipse glasses. And so, in the past few months, a cottage industry has sprung up to accommodate this market need. The problem is that many of these newly arrived sellers of solar eclipse glasses are fly-by-night manufacturers looking to turn a quick profit by selling subpar and potentially dangerous goods to unsuspecting Americans.

The first stop for most seeking a pair of eclipse glasses is likely to be Amazon, where there are literally thousands of listings for the devices, ranging in materials from cardboard to bronze. I, too, went on Amazon to scout out a pair. I picked more or less at random: I chose a cheap pack of 10 cardboard glasses with five different designs, at least two of which were not garishly jingoistic. About a week after I bought them, I had a thought: Maybe I should double-check to make sure they met safety standards set by the scientific community. Next stop: NASA.

NASA, of course, has a website dedicated to the 2017 eclipse, and on it, they have a section dedicated to eclipse-viewing safety. The site says that eclipse-viewing glasses must meet a few basic criteria:

- Have ISO 12312-2 certification (that is, having been certified as passing a particular set of tests set forth by the International Organization of Standardization)

- Have the manufacturer’s name and address printed somewhere on the product

- Not be older than three years, or have scratched or wrinkled lenses

NASA also names a few trustworthy lens brands: “Our partner the American Astronomical Society has verified that these five manufacturers are making eclipse glasses and handheld solar viewers that meet the ISO 12312-2 international standard for such products: American Paper Optics, Baader Planetarium (AstroSolar Silver/Gold film only), Rainbow Symphony, Thousand Oaks Optical, and TSE 17.”

I checked the ones I’d bought. ISO 12312-2: check. Manufacturer: American Paper Optics. Did I happen to roll a seven, or were most of the products on Amazon safe by NASA standards? I decided to check.

With the help of a handful of other Quartz reporters, I went through the first 140 listings that show up when you search Amazon for “eclipse glasses.” (Note that because of Amazon’s algorithms, not all of us saw the exact same listings in the exact same order. However, we believe that, combined, these searches provide a pretty good picture of what the average Amazon user might see.) Our search results included 25 “Sponsored” listings, 10 “Best Sellers,” and one “Bill Nye Exclusive.” Only 16 claimed to use lenses manufactured by one of the NASA-approved companies. Four of the bestsellers and the Bill Nye Exclusives are listed as manufactured by American Paper Optics; none of the rest of the bestsellers, and none of the 25 sponsored listings, were made by a NASA-approved company. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’re unsafe—but it does raise questions about who exactly is making these devices, and whether they’re producing them with safety in mind.

Andrew Lunt says he predicted that huge demand for eclipse glasses would lead to some problem or another. His Tucson, Arizona-based business Lunt Solar Systems, through their sister company TSE17, sold eclipse glasses in Germany leading up to the solar eclipse there in 2015. “In Germany, people were rioting in the street because the government mandated people without glasses had to stay indoors,” Lunt recalls.

He says that two years ago, he tried to gin up concern about the possibility that unmet demand could lead to similar unrest, or create openings for opportunists to swoop in, when the 2017 eclipse made its path across the US. But no one was interested. “You only know if you’ve been through it,” he says.

NASA seems to be scrambling to deal with the growing eclipse-glasses market as well. “Everything was going along fine until the public started to wake up to the eclipse and started buying things that may or may not be safe,” says Rick Fienberg, an astronomist and press officer at the American Astronomical Society, who has helped lead the charge in verifying the safety of various eclipse glasses. “Now they are peppering us and NASA with questions.”

Every manufacturer Quartz talked to spoke of nearly unfathomable sales growth in recent weeks. “We are increasing [sales] by 30-40% a day, 400-500% per week,” says Lunt. His company’s projections suggest that in the week prior to the eclipse itself, it will sell in the ballpark of 7-8 million eclipse glasses.

But if you search for “eclipse glasses” on Amazon, Lunt’s TSE17 lenses don’t show up anywhere near the first 100 results. Those are filled, almost entirely, with sellers like Summstar, which sells HDMI splitters and lightbulbs alongside supposedly sun-safe glasses, and Habibee, which sells a bewildering mix of things like brightly colored plastic hairclips, nail polish, and men’s suspenders.

All of the NASA-approved manufacturers are specialists, making only lenses or astronomical gear. Most have also been in business for decades, and are well-known within the astronomy community and among eclipse-chasers. You can go to their websites and see where they source their parts, what companies did their certifications, and where you can find their factories. The Amazon sellers, on the other hand, typically sell a handful of random products—often recent fad items like fidget-spinners—and provide neither sourcing nor contact information.

“It’s all nonsense,” says Mark Margolis of Reseda, California-based, NASA-approved Rainbow Symphony. “There are a zillion companies putting out the same product and they all have different names. And this isn’t because I don’t want competition in the marketplace. We’re oversold and on backorder. It’s not my motive to keep competitors out of the market.”

Of the 140 Amazon listings reviewed by Quartz, 119 of 140 claimed to have the proper ISO certification. Some even say they are just as good as the NASA-approved manufacturers, but haven’t gotten approval yet.

Fienberg, of the American Astronomical Society, has been in contact with many companies not yet on the NASA-approved list. “My phone keeps ringing” with companies asking for the NASA stamp of approval, he says. “We started collecting additional paperwork and what do you know—some don’t have complete ISO paperwork.”

When this happens, Fienberg or others on his team will attempt to work with the company to figure out what’s missing and fill in the gaps. “Some of them are in the process of trying to fix it and others have stopped talking to us. It’s a moving target,” he says.

For example, Fienberg spoke to an American representative of one Chinese company, and asked for and received their certification papers. “I said it doesn’t pass muster, and told him to send it to the ICS labs”—one of the more well-known ISO accreditation labs in the US. “I haven’t heard anything since. That was about two weeks ago.”

As for the next item on NASA’s safety checklist—identifying the name of the lens manufacturer—of the 140 Amazon listings reviewed by Quartz, a total of 33 identified the name. American Paper Optics was named on 13 of these; the second-most common name was Solar Eclipse International, allegedly a Canadian lens manufacturer. Many of the others that list no name make a point to note that their lenses are manufactured in Canada as well. It’s unclear, though, whether Solar Eclipse International actually manufactures anything in Canada. The Toronto address on their website is for a residential high-rise building, and detailed questions to the company’s spokesperson went unanswered. The only response provided was:

Regarding the ISO qualification, the full testing report has 16 pages, and all details are listed inside. All of our products are quality ensured with CE certified under ISO 12312-2:2015 international standards. Our certification can be verified online, and you can contact the testing company at your needs.

NASA, too, is looking into Solar Eclipse International. “I have their samples,” says Fienberg. “I have their ISO certification and it is deficient. It is not complete.” Fienberg says that the documentation is missing a whole section on labeling and packaging. (Quartz also obtained the ISO certification documentation and confirmed Fienberg’s allegation. The certification was done by a Chinese company, at a Chinese factory, which adds evidence to the possibility that “Canadian-made” is not exactly accurate.) That in and of itself doesn’t mean the lenses are unsafe. But Fienberg sees it as a red flag that makes him question the certification as a whole: “You can’t say it’s certified to the ISO standard if it doesn’t pass all the tests in the ISO standards.”

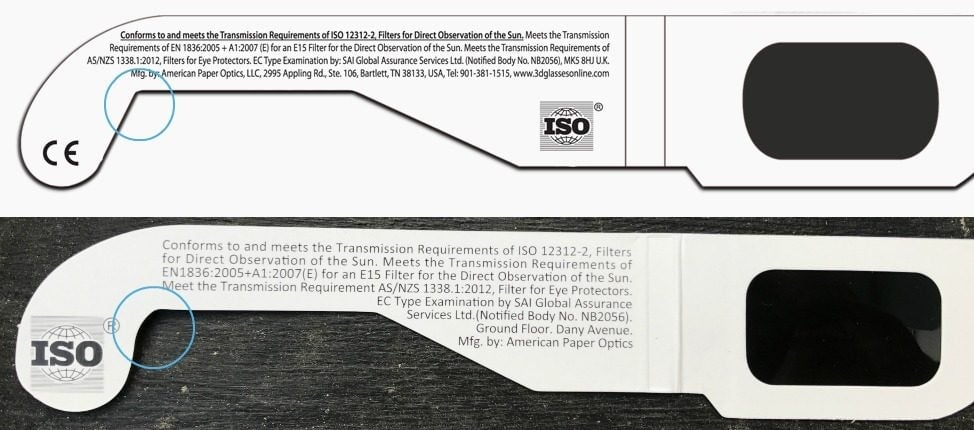

Lunt, of TSE17, says he has been in talks with Amazon about keeping counterfeit glasses off the online marketplace. He’s been buying samples from Amazon sellers and testing them, both on whether their lenses are up to standard and whether they’re actually made by the company stamped on the product, to get a sense of the scope of the problem. Working with other manufacturers, like American Paper Optics (APO), who are ostensibly his competitors, Lunt’s found many counterfeits. APO in particular is being counterfeited “quite a lot,” he says—which might explain why nearly 10% of the Amazon listings Quartz sampled claimed to be APO.

APO itself has done the same. Jason Lewin, the company’s director of marketing, says APO started to notice the counterfeits showing up on Amazon about a month ago. Since then, they’ve ordered some of the products, tested them, and sent Amazon photos and documentation of the counterfeits. Both Lewin and APO president John Jerit have been frustrated by the lack of response. They’re late to the game with this,” says Jerit. “Some of the legitimate resellers we’ve got, they’ve been complaining and complaining about this.

“[Counterfeiting] isn’t new to Amazon but this isn’t fidget spinners,” adds Lewin. “These are supposed to be things to keep you safe.”

All this has made me suspicious about my own glasses. The ones I bought have all the right words printed on them: “meets the Transmission Requirements of ISO 12312-2” they say, before going on to list a slew of other standards allegedly met. Then at the end: “Mfg. by: American Paper Optics.”

But the Amazon listing didn’t actually say American Paper Optics manufactured the lenses; it just showed up with the Tennessee-based company’s stamp on it. I ask Lunt how I could tell if what I had was the real deal or a knock-off, and he tells me to look at the earpieces. There’s a design element that’s been generic among all of cardboard glasses for years (remember those red-and-blue lensed 3D glasses?): the part of the cardboard frame that hooks over the ears has a rounded end. APO recently changed their design to have a more squared-off earpiece.

No surprise, my 10-pack all have rounded ears, the scarlet letter of phoniness.

Fienberg says the AAS and NASA plan to release new information in the coming days approving additional manufacturers, and he continues to be overwhelmed by company requests for reviews. He also expects retail chains like Lowes and Walmart to soon begin selling eclipse glasses, and he plans to work closely with them on their approval process. “I’m going to list companies I know for sure are selling safe glasses and the way I know for sure is I’ve talked not just to them but the manufacturers that are supplying them,” says Fienberg. “We know they have been tested and we’ve handled them ourselves.”

In the meanwhile, here’s the real question: How much does it matter if you wind up with a pair of glasses that don’t meet NASA safety standards? “All the testing I’ve done have shown that the products are very bright but are not unsafe,” says Lunt. Tests done on a spectrophotometer—a lab-level machine that costs thousands, in case you were wondering if you could check your glasses yourself at home—show that the lenses are, in fact, blocking the most harmful spectra of light. “The IP is getting ripped off, but the good news is there are no long-term harmful effects,” says Lunt.

That said, in this sort of high-demand environment, it’s easy to imagine an unscrupulous dealer coming in and making no effort at all to create a safe product before listing it on Amazon. “Just today I got a call for someone looking for 125,000 glasses,” said Lunt on July 26. “When we start running out and we will, people will buy anything.”

On July 27, Amazon sent out a letter to sellers of eclipse glasses and products with an update to their policy: sellers will now have to submit for approval and provide details of safety and origin, including ISO certification from an accredited lab. But it remains unclear what will happen to those already on their marketplace. (Amazon did not respond to multiple queries from Quartz. We’ve reached out to them again for confirmation and will update this post if and when we hear back.)

“Hopefully what they’ve done—putting a policy in place—will do something,” says Lewin, of APO. “Anything will help. It will all come down to the next couple of weeks.”

Additional reporting by Chris Groskopf, Ephrat Livni, Zoë Schlanger, and Katherine Ellen Foley.