Why gay Americans have won the right to get married but can still be fired for being gay

Most countries that have enabled same-sex marriage had a ban on workplace discrimination against gay people first. Yet in the US, even though the US Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that gay people can get married, it has yet to rule that they cannot be fired for their sexual orientation.

Most countries that have enabled same-sex marriage had a ban on workplace discrimination against gay people first. Yet in the US, even though the US Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that gay people can get married, it has yet to rule that they cannot be fired for their sexual orientation.

In the last couple of years, federal courts have begun seriously debating whether Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which bars discrimination in the workplace based on “race, color, religion, sex or national origin,” can be read as also including sexual orientation. Although most courts have until recently said it doesn’t, during the Obama administration the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), a federal agency, began treating cases of discrimination based on sexual orientation as a Title VII violation.

But under president Donald Trump the government’s position has changed—or rather, it has split. In a case now pending appeal in the 2nd Circuit, Zarda v Altitude Express, a sky-diving instructor (or rather his estate, since he later died in an accident) is suing his employer, which allegedly fired him for being gay. The EEOC is supporting his case (pdf), but the Department of Justice on July 26th filed an amicus brief (pdf) opposing it. “The sole question here is whether, as a matter of law, Title VII reaches sexual orientation discrimination,” says the DOJ’s brief. “It does not, as has been settled for decades.”

It has not, in fact, been settled, as the more recent court rulings show. But it could soon be settled in the Supreme Court, and the decision won’t necessarily be in gay people’s favor. So why is discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, which many Western countries outlawed years ago, still up for debate in the US?

An ambiguous law

One reason is that, remarkably, the question has never yet been put to the Supreme Court. The closest it came was in 1989, in Price Waterhouse vs Hopkins, when the court interpreted Title VII as prohibiting workplace discrimination based not only on sex but also on sex stereotypes, such as ideas about how men or women should dress and act.

That case wasn’t about sexual orientation specifically, however, and it wasn’t until the Obama administration that the argument that Title VII encompasses sexual orientation started to gather steam, according to Paul Smith, vice president of litigation and strategy at the Campaign Legal Center.

The recent court rulings are the fruits of that argument. In April, a three-judge panel in the 7th Circuit decided, in Hively vs Ivy Tech Community College (pdf), that “discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is a form of sex discrimination.” It relied in part on the Hopkins decision, ruling that heterosexuality was itself a sex stereotype—the notion that men should always partner with women and women with men.

In March, on the other hand, a judge in the 11th Circuit decided in Evans v Georgia Regional Hospital (pdf) that Title VII “was not intended to cover discrimination against homosexuals.” And in Zarda, a three-judge panel of the 2nd Circuit dismissed the skydiving instructor’s claim in April. The court then agreed to hear his appeal again en banc—meaning with all 11 judges present, giving the decision more weight.

One of these cases—most likely Evans, because it “is ahead of the Zarda case,” says Smith—is likely to be submitted to the Supreme Court. If the court decides to hear the case, which experts think it will, the ruling could go either way—but it’s especially likely to go against including sexual orientation in Title VII if Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the court, retires, as he is reportedly considering doing, and Trump replaces him with a more conservative judge.

If the court doesn’t uphold sexual orientation as part of Title VII, then enshrining it would require a new law. But why isn’t there one already?

A lack of legislative drive

In 2013, a HuffPost/YouGov poll found that 52% of Americans (pdf) “favored a law prohibiting discrimination by employers against gays and lesbians.” Support for same-sex marriage, made legal in 2015, is at an all-time high this year, at 62%, according to the Pew Research Center.

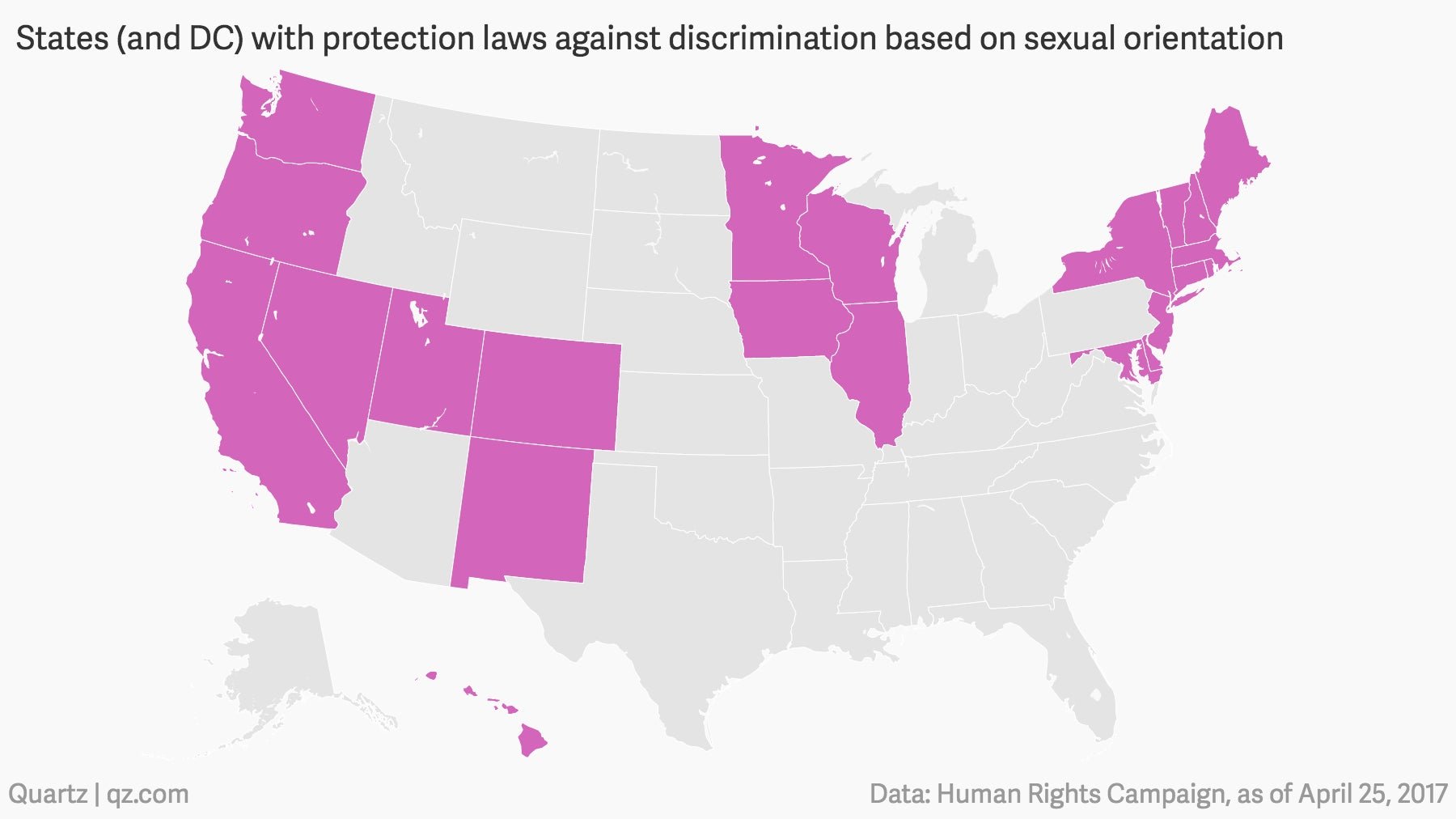

However, only 22 states and the District of Columbia have state-laws that protect against workplace sexual orientation discrimination, and attempts to pass a federal law have always failed.

The first such attempt was in 1974, with the Equality Act. A measure far ahead of its time, it would have outlawed discrimination for sexual orientation not only in employment but also in housing and public accommodations. It didn’t pass. In 1994, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) was introduced in Congress, and has been re-introduced in almost every session of Congress since then. A new, even broader Equality Act was introduced in 2015, which would ban discrimination also in such areas as retail, credit ratings, and jury selection. It too has languished.

Experts say the reasons why those attempts have failed while the same-sex marriage campaign succeeded have to do with the universality of love and with political clout. Marriage equality had a lot of political momentum because there were “public campaigns around it” and “a lot of LGBT organizations got behind that cause”, says Christy Mallory, state and local policy director at the Williams Institute, a think tank part of UCLA that focuses on law and gender. ”People sort-of understood the importance of marriage in their own lives and that really resonated with them.”

There is a class element too, says James Richardson, an associate of Sanford, Heisler, and Sharp LLP. Marriage-equality campaigns received considerable funding and support from people in higher social classes, people who were able to “get the ear of their representative.” Also, they were likely people from states like California, New York, and DC that already protected them from workplace discrimination (in some cases since the 1970s). “Marriage was on their radar,” says Richardson. “The prospect of being fired just for being gay was not”.

Richardson says there’s also rarely a “smoking gun” when it comes to discrimination, making the issue harder to see. “Conversations that might provide evidence for a discrimination claim are held in person rather than over e-mail.” Most people “don’t see, especially if they’re not a person of color, workplace discrimination every day,” says Brian Silva, executive director of Marriage Equality, one of the organizations at the head of the marriage equality movement. “So when they hear those stories [of workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation], they have a higher level of doubt on whether something like that exists.”