Five lessons for hyped IPOs, including: Don’t always believe the hype

The big internet IPOs of the last few years have had bumpy rides. Last week, Facebook shares went above their IPO price for only the first time since the company went public over a year ago. Zynga and Groupon have lost billions of dollars in valuation since going public. On the other hand, LinkedIn is now worth about six times the $4.3 billion valuation at which it launched.

The big internet IPOs of the last few years have had bumpy rides. Last week, Facebook shares went above their IPO price for only the first time since the company went public over a year ago. Zynga and Groupon have lost billions of dollars in valuation since going public. On the other hand, LinkedIn is now worth about six times the $4.3 billion valuation at which it launched.

And now a new crop of highly anticipated IPOs are coming up. They include China’s largest e-commerce company, Alibaba Group, the online file storage company Dropbox, and Twitter (whose CEO, Dick Costolo, is pictured above). Here are some lessons for them, gleaned from the last batch.

1. Don’t confuse a hot Internet IPO with a mega IPO

Some hot Internet IPOs are oversubscribed 25 times. But the biggest public offerings have fewer would-be buyers per share just because of their sheer size. Confusing the two kinds of IPO can mess up estimates of demand, and thus the offering size and price.

For instance, some have argued that Facebook, which raised $16 billion on a valuation of $104 billion, was treated as a hot Internet IPO when it should have been a “mega IPO,” more along the lines of General Motors (which raised $20 billion on a $50 billion valuation in 2010) and Visa. Demand for Facebook shares was less than expected, partly because the offering size and price went up just before it went public. A more internet-style IPO is LinkedIn, which raised $352 million at a valuation of $4.3 billion in 2011.

Alibaba Group could fall under the “mega IPO” label because of its sheer size. Valuations for the company range from a conservative $75 billion to a more ambitious $100 billion. Twitter raised money earlier this year at a $10 billion valuation, but by the time it goes public, which could be as early as next year, its valuation will likely go up. It may be in line with Groupon, which raised $700 million in its IPO at a valuation of nearly $13 billion.

2. Leaving some money on the table can be a good thing

One big decision for a newly public company is how it wants its stock to perform once it starts trading. Some companies like to have a “pop”—see their stock price go up, which makes the investors who bought the stock happy. Stocks that don’t pop are often seen as unsuccessful. But a pop also means “leaving money on the table”—profits that go to shareholders instead of to the company.

This is a fine line to tread. Facebook, unlike some previous tech firms, did not try for a big pop, and the company, its founders and early investors made a lot of money from the IPO. But the fall in Facebook’s share price—exacerbated by technological glitches at the start of trading—angered investors, and some inexperienced small-time buyers lost a lot of their savings.

3. It’s better to under-promise and over-deliver

LinkedIn, by contrast, saw its stock price more than double at its debut, leading some to argue that it left too much money on the table. The flipside is that the goodwill this generated from investors, LinkedIn employees and others who bought its stock may have helped the company. Because LinkedIn shares have risen so much, it’s seen as having a lot of momentum and potential to grow further.

Both Facebook and LinkedIn’s experience show that an IPO’s performance and its reception can affect a company’s brand. If an IPO goes well according to market and media expectations, it can be great PR for the company.

4. Don’t always believe your own hype

Most company executives and founders experience going public only once. It’s exciting to come from having just a handful of employees and shoestring financing to being worth billions of dollars, and it’s easy to get caught up in all the praise from bankers angling for a part of your IPO business.

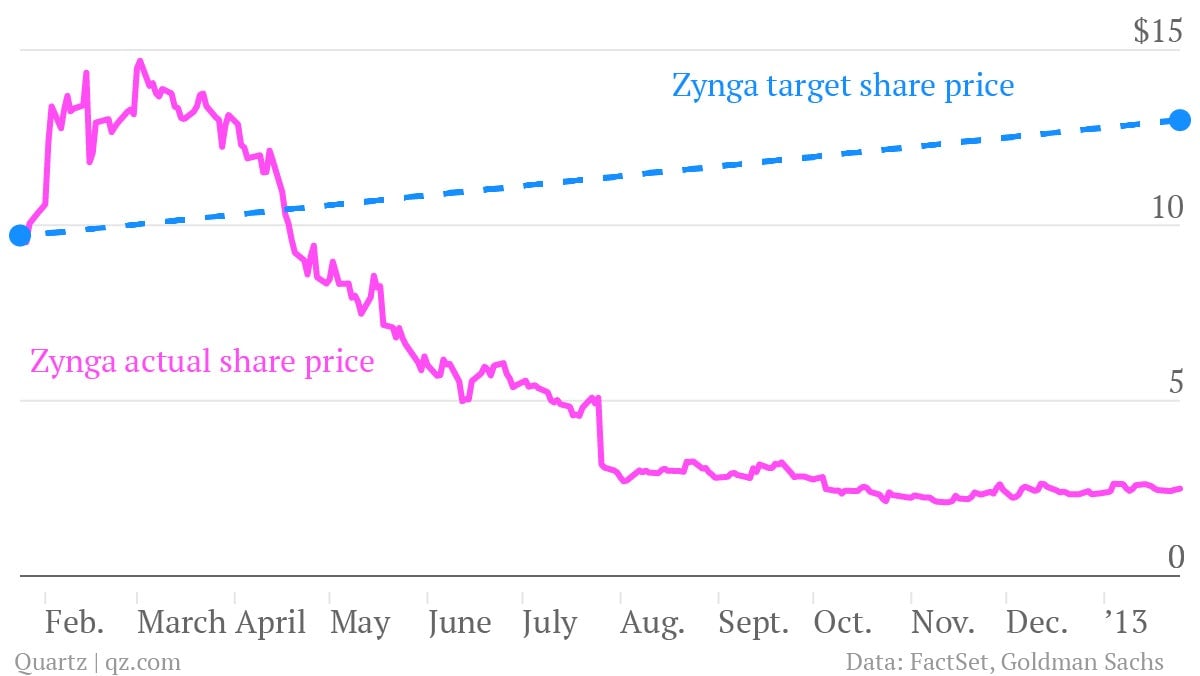

But those high expectations can come back to haunt you. Remember what investors will care about: your user or customer growth, ability to generate revenue, and whether your strategy fits with how the market is evolving. A hiring spree may lead to buyer’s remorse later, as it did recently for Zynga, which laid off over 500 people in June. Airbnb decided to scale back (paywall) its international ambitions to avoid being a cautionary tale. Twitter is facing similar questions about its overseas expansion.

Similarly, while opportunistic bankers have told Alibaba it could easily surpass a $100 billion valuation, its founder, Jack Ma, has tried to be more cautious. He still remembers the IPO of its web portal Alibaba.com, which connects businesses looking to import and export Chinese goods. Alibaba.com raised $1.7 billion in 2007 when it went public in Hong Kong—at that time the biggest Internet IPO since Google. But after it failed to meet investor expectations, Alibaba.com ended up going private again in 2012.

5. It’s all about execution

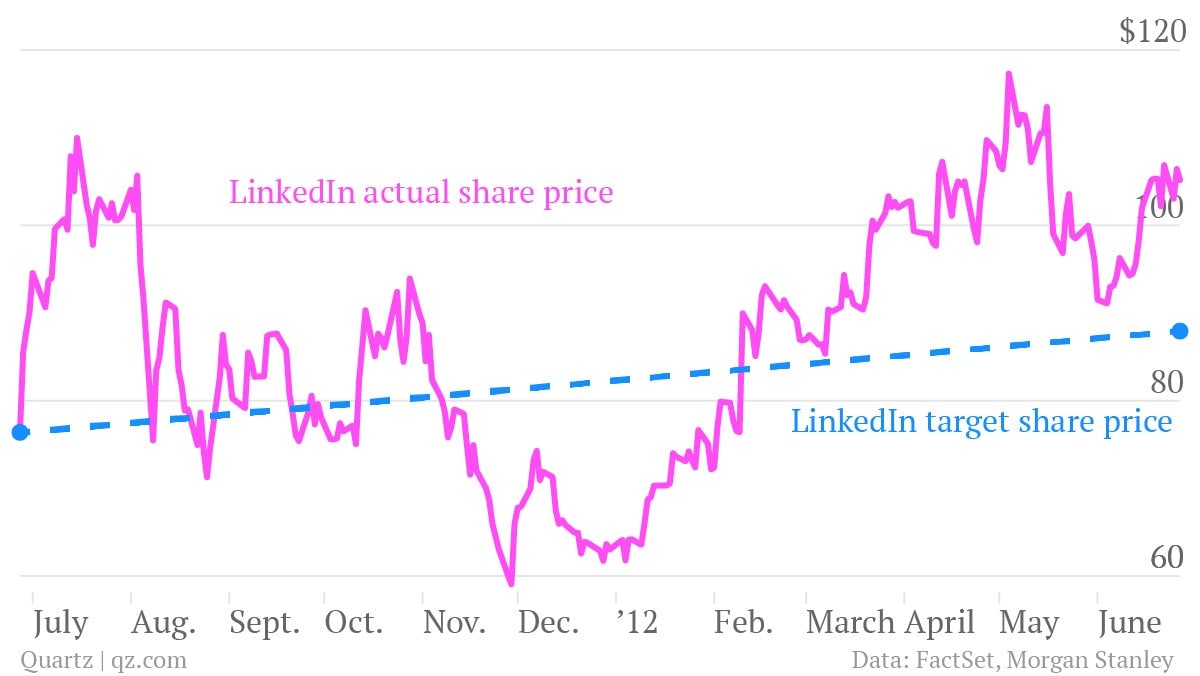

In the long run, a company is judged based on how management executes on its plans. And the acid test is to compare the first analyst report on a company, which usually comes out just after the IPO and contains a one-year price target based on the company’s plans, with how it actually did a year later.

The charts below on various companies’ first year post-IPO show what the market already knows: Facebook and Zynga didn’t meet expectations (although Facebook has done a better job recently by increasing mobile ad revenues, hence its return to an above-IPO valuation). The Goldman Sachs analyst report on Zynga from January 2012 says “risks include ability to continue to generate hit games and engage users over the life of the game; balancing monetization and user growth as online gaming models evolve; competition, given low cost of game development.” Those risks all came true.

By contrast, in its first analyst report on LinkedIn in July 2011, Morgan Stanley was pretty bullish, saying it believed LinkedIn would be able to maintain its competitive position, increase user engagement, and increase margins. It predicted that the share price a year hence could reach as high as $130. LinkedIn stock hit that level earlier this year and is now trading around $232.