Many apparel workers are paid less now than 10 years ago

Are sweatshops really an engine of prosperity?

Are sweatshops really an engine of prosperity?

New research reveals that the average wages earned by the people who make clothing imported by the US and other wealthy countries don’t always go up. That challenges the idea that low-skilled labor making cheap goods is necessarily the first step up the value chain toward a more prosperous economy.

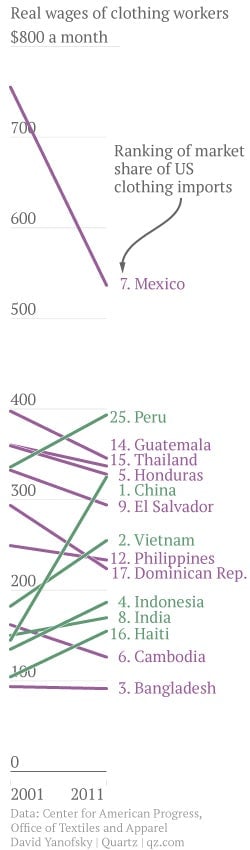

Researchers at the Center for American Progress measured the change in monthly wages for apparel workers from 2001 to 2011 in 15 of the top 21 countries exporting clothing to the US. In most of those countries, wages declined. Bangladesh, where the deadly collapse of a factory has drawn global attention to working conditions in clothing manufacture, has seen wages remain flat for years, while wages in Mexico, once the largest US apparel manufacturer, declined by nearly 30%. Clearly, clothing mills alone aren’t the way to develop a wealthier workforce.

But the six countries exporting the most apparel to the US—and with the largest populations—have all seen increases in their wages. This group is lead by China, with 42% of apparel imports, but also includes India, Peru, Vietnam, Haiti, and Indonesia. (Pakistan, the 10th largest US apparel exporter, was not included in the study.)

The remaining nine countries—Mexico, Guatemala, Thailand, Honduras, El Salvador, the Philippines, the Dominican Republic, Cambodia and Bangladesh—saw wages for clothing workers go down between 2001 and 2011.

The driving reason? Competition from China, which increased its share of apparel exports to the US significantly since a trade normalization agreement between the two countries in 2000. Today, the falling-wage countries only make 27% of the clothing the US imports, but in 2000 Mexico alone exported more than twice as much apparel to the US as China did.

China’s success has allowed it to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but it has also lead to wage cuts in competitor countries as they sought an advantage over the Chinese juggernaut. They’ve been able to maintain both wage increases and their large market share, the researchers say, because of investments that increase worker productivity and a policy of increasing wages to forestall social unrest.

Manufacturers on the hunt for the cheapest labor have already begun to look beyond China, seesawing back to places, like Bangladesh, where they think they can get the most bang for their buck. While wages aren’t the only determinant of moves like these, they play large part, which is why worker advocates want companies to invest more in their supply chains, and countries to institute more generous minimum wage policies, which helped boost workers earnings in most of the countries that saw gains.