Poorly designed public toilets aren’t just annoying, they’re dehumanizing

Most people will never see the world like Sinéad Burke does. Standing at just 3’ 5″ (105.5 cm), the 26-year old PhD student encounters obstacles in public spaces that most of us take for granted. From the height of the coffee counter in Starbucks to the carousel in an airport security line, she faces hurdles in the architecture of public spaces every day.

Most people will never see the world like Sinéad Burke does. Standing at just 3’ 5″ (105.5 cm), the 26-year old PhD student encounters obstacles in public spaces that most of us take for granted. From the height of the coffee counter in Starbucks to the carousel in an airport security line, she faces hurdles in the architecture of public spaces every day.

Burke has a genetic bone growth disorder called achondroplasia, which results in severely shortened arms and legs. For her, poorly-designed spaces aren’t just annoying, they’re dehumanizing. Public bathrooms are the worst, she says. The agony starts when Burke enters the cubicle and cannot reach the lock on the door, as she describes in a recent TED talk.

I can’t reach the lock on the door. I’m creative and resilient. I look around and see if there’s a bin that I can turn upside down. Is it safe? Not really. Is it hygienic and sanitary? Definitely not. But the alternative is much worse. If that doesn’t work, I use my phone. It gives me an additional four- to six-inch reach, and I try to jam the lock closed with my iPhone. Now, I imagine that’s not what Jony Ive had in mind when he designed the iPhone, but it works.

The alternative is that I approach a stranger. I apologize profusely and I ask them to stand guard outside my cubicle door. They do and I emerge grateful but absolutely mortified, and hope that they didn’t notice that I left the bathroom without washing my hands. I carry hand sanitizer with me every single day because the sink, soap dispenser, hand dryer and mirror are all out of my reach.

Despite laws requiring businesses to build accommodations for the disabled, there’s still no ideal bathroom scenario for customers like Burke.In accessible stalls, she can reach the lock, the mirror, sink, the soap dispenser and the hand dryer—but she can’t use the toilet, which is purposely designed higher for wheelchair users.

“For me the bathroom is a very physical symbol of an individual’s human rights and dignity.” says Burke, who is studying human rights education at Trinity College, Dublin. “Design shouldn’t inhibit a person’s autonomy, agency, and ability to socialize and be their whole person. For me a bathroom is a very tangible identifier of how design can impact a person’s life.”

Burke’s extreme case should be a wakeup call to architects, business owners and lawmakers shaping the design of public amenities.

Often, when we think of “accessible design,” we think of people in wheelchairs, hearing aids or dark glasses for the blind.

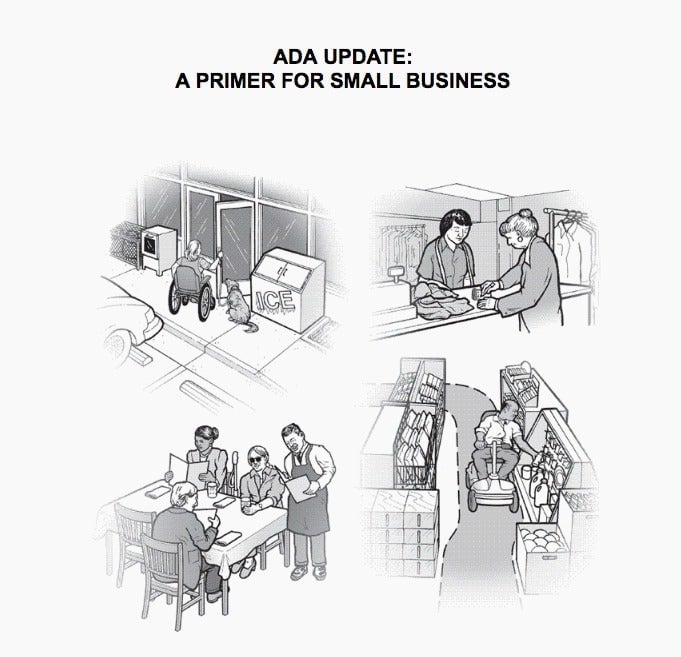

But this lack of nuance—even in the illustrations of ADA manuals—limits the designer’s imagination. The American Disabilities Act definition of disability is broad—”as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities”—and it does not specify any single impairment.

“I have a very visible physical disability, but there are thousands in the population who have an invisible disability,” notes Burke. The US Survey of Income and Program Participation Statistics, shows that 74% of Americans with severe disabilities are not in wheelchairs.

Burke argues that companies who address only the bare requirements of ADA regulations are missing out on a significant segment of their customers. About 15% of the world’s population—about a billion people—have some form of disability, according to World Bank data. Burke explains that the disabled’s friends and families are more likely to visit establishments that make everyone in the group feel comfortable.

Better accommodations don’t need to be drastic or expensive. Speaking to Quartz from a cafe in Dublin, Burke says she frequents Accents Coffee and Tea Lounge not for the coffee, but because of their chairs. “Not only do they have chairs and sofas but they have bean bags,” says Burke. “If my legs aren’t supported, they just dangle and I get pins and needles and I get this numbness. Usually, I sit on the floor but that’s not very comfortable.”

‘There are so many aspects to the design of these different facilities,” says Burke. “I think those with the most power and influence have a responsibility to instigate the conversations in their offices to ask, ‘What can we do?'”