China’s devastated wheat crop could spur more food deals

A combination of frost and too much rain has wreaked havoc on China’s wheat crops, Reuters reported Tuesday, which could force the country to ramp up wheat imports.

A combination of frost and too much rain has wreaked havoc on China’s wheat crops, Reuters reported Tuesday, which could force the country to ramp up wheat imports.

Food supplies are already tight for China’s 1.35 billion people. The country ranks a lowly 42nd in the world in food security, just ahead of Botswana. Urbanization has made arable land scarce, persistent food safety scandals have made consumers nervous, and volatile food prices are driving inflation. So the failed wheat crop may induce Beijing to encourage even more acquisitions of foreign food companies to secure the technology and natural resources that China needs to feed its many hungry mouths.

China’s food scarcity worries are already playing a major role in deal-making around the world. The $5.6 billion purchase of US soybean grower Gavilon by Japan’s Marubeni Corp was held up by Chinese officials for nearly a year, and then only approved with strict rules for the combined company, which will provide a huge portion of China’s soybean imports.

Then in May, China’s Shuanghui International offered $4.7 billion for Smithfield, the United States’ largest pork producer, prompting US politicians to fret about whether China was bolstering its strategic pork reserves at America’s expense. Ben Becker, the press secretary for the Senate Agriculture Committee, worried aloud to the New York Times. “What if tomorrow it is the biggest dairy producer? Or the biggest corn producer?” Then America, he seemed to imply, could run out of milk or corn.

Such fears are often overblown. After all, “It’s not as if China can order the world’s pigs to stop reproducing,” the Times noted, adding that agricultural economists say it would only be a few years before the rest of America pork-packing plants could replace the lost capacity, even if all of Smithfield’s pigs were eaten by China. And China isn’t after Smithfield’s pigs—it’s after the company’s expertise in running an efficient (if occasionally very gross) protein-based supply chain.

It’s implausible to think that China would be willing or able to simply scoop up a massive dairy company like Nestle or Danone, or a leading corn processor like Archers Daniel Midland. But the world’s top dairy producers, already in the throes of a consolidation wave, are only going to see more deals, analysts predicted even before China’s recent wheat crop disaster.

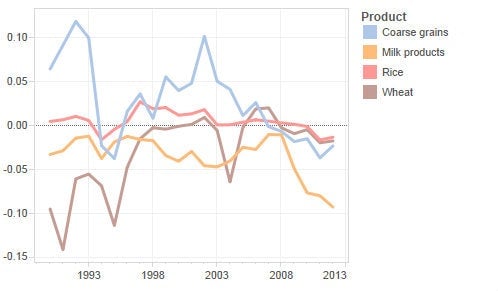

As data from a report by the OECD (above) shows, China already needs to import significant quantities of grains and dairy. The OECD expects China “will improve its food security and remain self-sufficient in main food crops,” but will also “slightly outpace its production growth by some 0.3% p.a., similar to the trend of the previous decade.” It is that trend that will impact M&A—occasionally with China buying expertise, in the case of Smithfield, but more often in deals like Gavilon-Marubeni, where global players consolidate to better meet massive Chinese demand.

And there is certainly room for further business opportunities if China’s crops fail to meet their targets, as with this year’s wheat harvests. Foreign traders and analysts estimated to Reuters that China will now need to import some 10 million metric tons of wheat, nearly double the previous estimates and the most in a decade. With China facing changing food demands from better-off consumers and massive soil contamination from its decades of industrial production, Beijing may be pushed to do even more grocery shopping overseas.