Trump’s fire-and-fury messages channel Steve Bannon’s apocalyptic visions

In late July, North Korea tested a type of missile some say can hit Chicago, announcing that “packs of wolves are coming in attack to strangle a nation.” This week, US president Donald Trump hit back, vowing on Aug. 8 to attack North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” Pyongyang’s next move was a suggestion that it might bomb Guam, prompting Trump to take to Twitter to declare that “military solutions are now fully in place, locked and loaded, should North Korea act unwisely.”

In late July, North Korea tested a type of missile some say can hit Chicago, announcing that “packs of wolves are coming in attack to strangle a nation.” This week, US president Donald Trump hit back, vowing on Aug. 8 to attack North Korea with “fire and fury like the world has never seen.” Pyongyang’s next move was a suggestion that it might bomb Guam, prompting Trump to take to Twitter to declare that “military solutions are now fully in place, locked and loaded, should North Korea act unwisely.”

Was this just macho posturing from the White House, or is Trump really ready to kick this word war up to World War level?

The escalation doesn’t seem to have been born from carefully calculated policy. Trump reportedly improvised his “fire and fury” line, taking John Kelly—the Marine general who’s supposed to be imposing discipline as the new White House chief of staff—by surprise. So where did Trump’s flash of apocalyptic menace come from? Possibly it came from practicing Clint Eastwood impressions in front of the mirror.

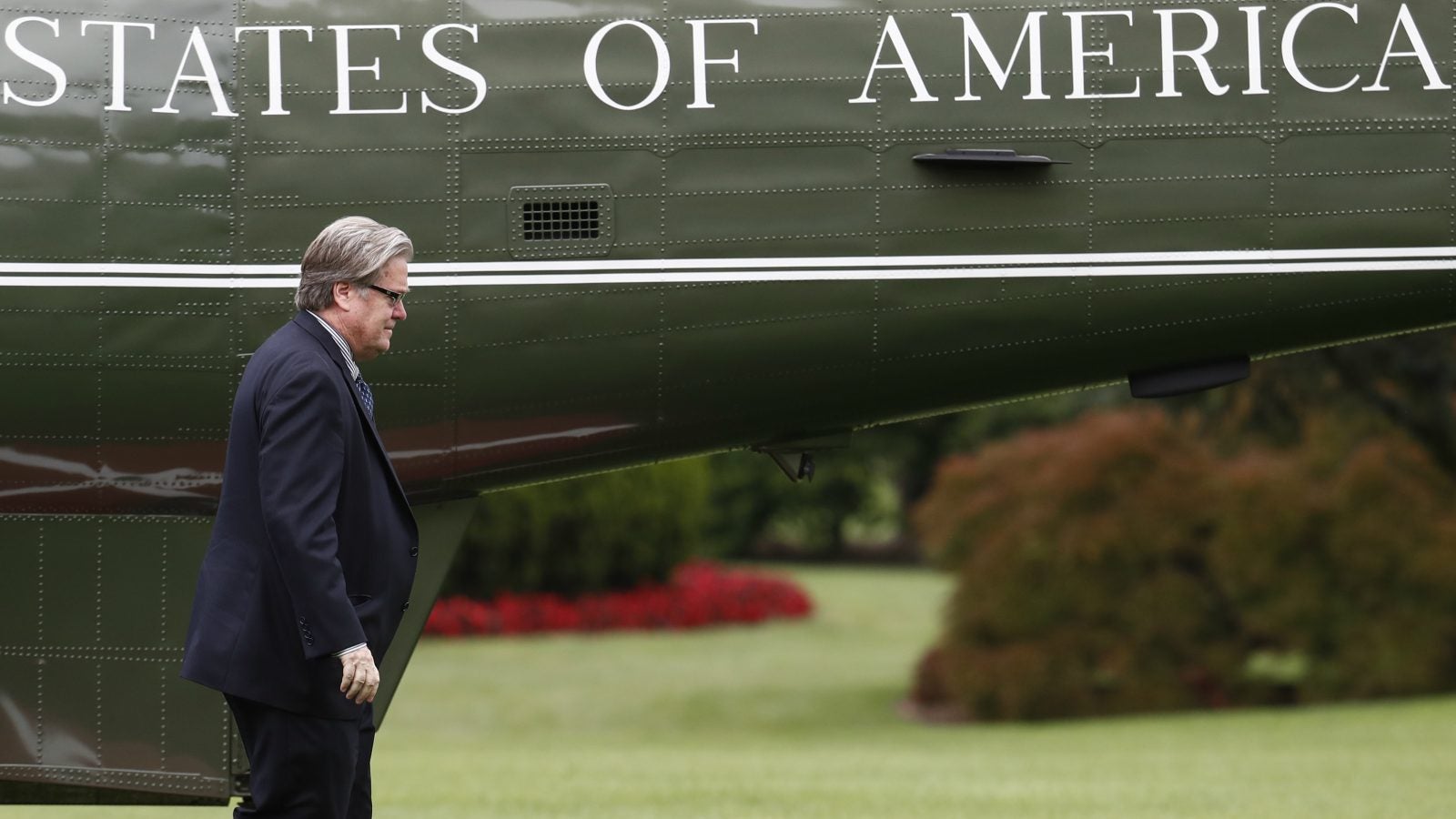

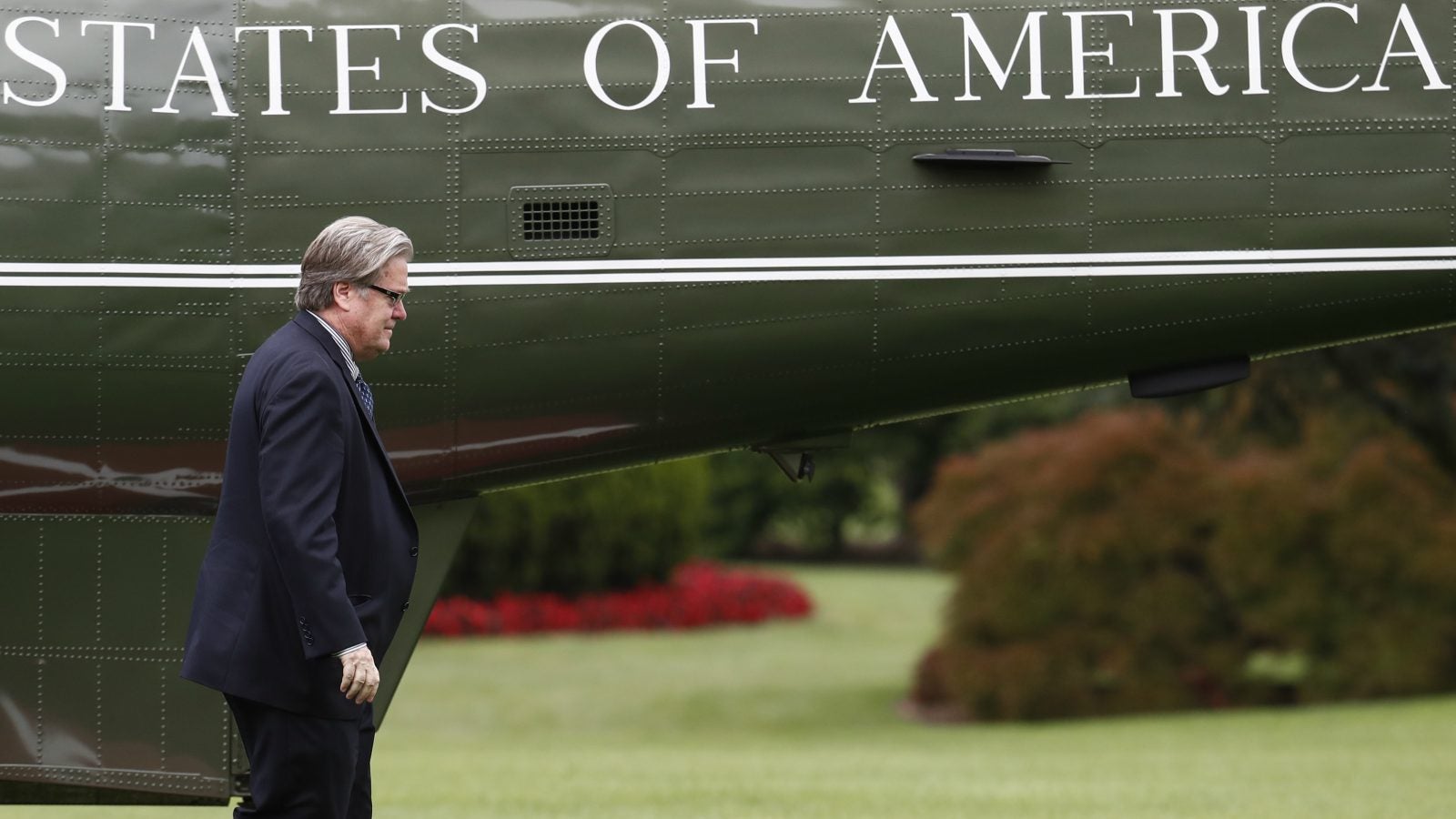

A more disquieting possibility, however, is that it came from his top adviser, Stephen K. Bannon. While it’s hard to know the influence Bannon’s worldview exerts on Trump, the worldview itself is plain to see, revealed over years of filmmaking, radio-show-hosting, and lecture-giving, as Quartz analyzed in more detail earlier this year.

A key part of the Bannon worldview is that big wars are needed to usher in new stages of civilization. Could that be what’s spurring Trump on?

First, let’s examine the “generations theory” that Bannon is a big fan of. Put forth by Neil Howe and William Strauss, two amateur historians, this theory views America as going through cycles lasting roughly 80 years. Each cycle is broken into four “turnings,” which are 20-year periods defined by a certain zeitgeist: “high,” “awakening,” “unraveling,” and “crisis.” As Bannon has remarked before, America entered the “Fourth Turning”—the crisis period—around 2008, when the financial crisis hit.

In February of this year, Neil Howe elaborated on what might happen over the course of this Turning, which he says will last until about 2030. The forecast includes intensifying nationalism, as well as war on the Korean peninsula:

Further adverse events, possibly another financial crisis or a major armed conflict, will galvanize public opinion and mobilize leaders to take more decisive action. Rising regionalism and nationalism around the world could lead to the fragmentation of major political entities (perhaps the European Union) and the outbreak of hostilities (perhaps in the South China Sea, the Korean Peninsula, the Baltic states or the Persian Gulf). Despite a new tilt toward isolationism, the United States could find itself at war.

War isn’t necessary to usher in a new epoch, says Howe. But no Fourth Turning has occurred without one—and major wars have a habit of falling within Fourth Turnings.

There are signs that Bannon, too, sees war as instrumental in pushing through to the next cycle. Historian David Kaiser has said that when Bannon interviewed him for his film Generation Zero, Bannon homed in on this point:

More than once during our interview, he pointed out that each of the three preceding crises had involved a great war, and those conflicts had increased in scope from the American Revolution through the Civil War to the Second World War. He expected a new and even bigger war as part of the current crisis, and he did not seem at all fazed by the prospect.

In his extensive career in film and radio, Bannon indeed has gabbed about a heck of a lot. Not about North Korea, though. In fact, Bannon is pretty mum on US defense strategy in general. This isn’t surprising; Bannon, a former naval officer with a daughter who’s served in the military, has decried that fact that it’s generally people from working-class families who fight America’s wars, while elite offspring frequently duck this sacrifice. And as Josh Green, author of an excellent new book about Bannon’s role in Trump’s victory, explains, Bannon has an “almost isolationist view of American foreign policy.”

There is one really big exception, though: Islamic terrorists. As Bannon said in 2014, “I believe you should take a very, very, very aggressive stance against radical Islam.” The fight against what he calls “Islamic fascists” is big: it’s a “global existential war,” Bannon said in 2016.

Kim’s regime is fascist, but Islamic it surely ain’t. And though a war with North Korea would inevitably involve a grievous waste of lives, the Hermit Kingdom doesn’t pose an existential threat to the US. Its cultish ideology, narrow ambitions, and inchoate economy also mean it doesn’t fit within a larger “global war against ___” theme. Of course, an American assault on North Korea could very likely lead to Korean peninsular chaos, including a much larger war between, say, South Korea and China. But even that conflict seems unlikely to hit the nationalism themes that stir Bannon’s base.

According to US News and World Report, Bannon supports dealing with North Korea as part of a broader China strategy and, basically, not dignifying Kim’s warmongering with a response. Then again, Bannon is at his core a nationalist—and if nationalist saber-rattling will help shore up Trump’s eroding base, North Korea is an obvious target.

Also worth noting is a shift in North Korea coverage at Breitbart News, which Bannon helmed until he took over Trump’s campaign. The site used to focus on North Korea’s actions and humanitarian atrocities mainly to the extent that they made former US president Barack Obama look weak.

The coverage of late, however, has been much more aggressive in tone, lionizing Trump in his showdown with an elite that wants to “appease” North Korea. For instance, an article on Aug. 11 railed against the “assumption that America must be humble before mighty North Korea, which can toss around as many threats as it wants, while top U.S. officials must choose their words very carefully.” The article then drew a connection between the Kim kerfuffle and Islamic terrorists: “Not coincidentally, that’s the same way the left thinks that’s also how we must handle radical Islam.”

Breitbart, it should be noted, seems to be taking cues from the White House. The clearest example emerges in a recent Breitbart interview with Sebastian Gorka, one of Bannon’s top lieutenants in the White House and former Brietbart editor. Gorka pushed the anti-appeasement line hard, blaming “the chattering classes” for a “belief that appeasement of dictatorial regimes” works out well for America or the West.

There seems to be a completely ahistorical sense of geopolitics. They missed the lessons of Hitler being appeased, of Russia being appeased, the Soviet Union, of Iran being appeased again and again and again. And they applied it to North Korea.

From there, Gorka lays out a worldview, including an enemy described in eerily broad terms.

“If you deny the existence of evil, you’ll say, ‘Yes, let’s have another conference in Vienna or Geneva and sit down with the mullahs or sit down with the rabid Stalinists [in North Korea] and see what agreement we can come to,'” said Gorka. “No. Wrong. These regimes are evil, and they must be dealt with as such.”