The location of internment camps had profound, long-lasting effects on Japanese-Americans assigned to them

Where you live matters: it influences your education, income, and much else besides. But it’s hard to measure whether people are better off in a certain place because of the place itself, or because of the kind of person they are (among many other factors). History offers few natural experiments to test the impact of environment on outcomes.

Where you live matters: it influences your education, income, and much else besides. But it’s hard to measure whether people are better off in a certain place because of the place itself, or because of the kind of person they are (among many other factors). History offers few natural experiments to test the impact of environment on outcomes.

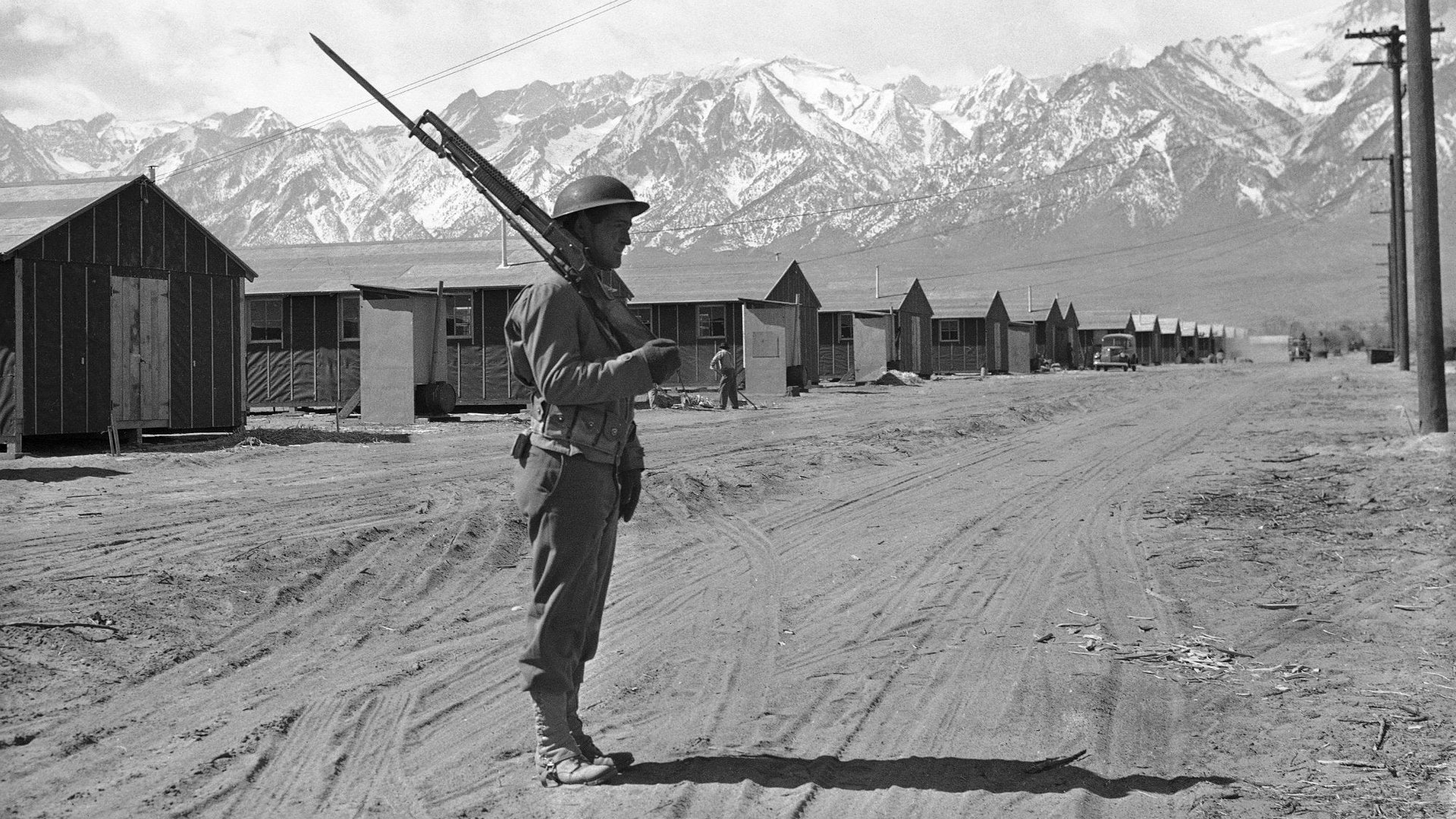

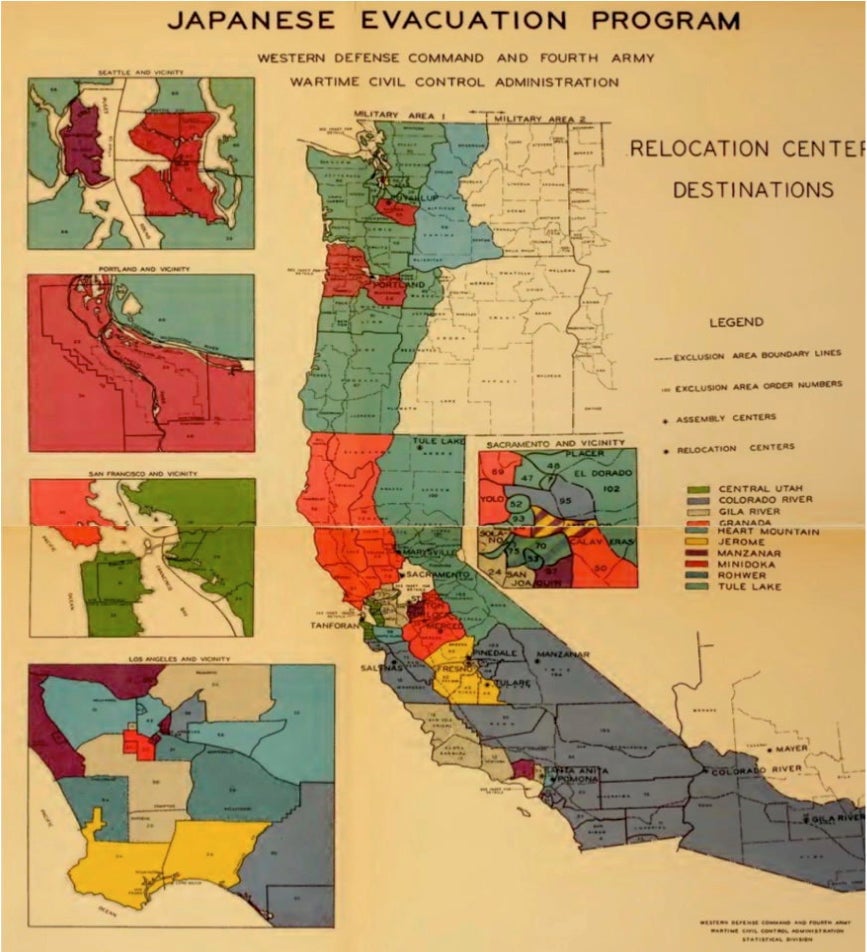

In 1942, the US government forcibly relocated over 100,000 Japanese-Americans to internment camps and held them for years. Locally, assignments were more or less random. In a working paper (pdf), Daniel Shoag of Harvard and Nicholas Carollo of UCLA use this randomness to study how the location of internment camps affected the lives of internees and their children far into the future.

“Although the Japanese internment was unquestionably a tragic episode in American history, the scale of the geographic randomization it entailed, along with nearly full follow up with survivors half a century after the initial treatment presents a rich source of data for economic analysis,” the researchers write.

In the 1990s, the US Department of Justice identified former internees in order to pay reparations, allowing the researchers to trace the journeys of more than 60,000 people sent to camps. Some 50 years later, internees were 16 percentage points more likely to live in the state of their camp than internees originally from the same city but sent to a different camp.

Knowing this, Shoag and Carollo looked at the lives of former internees in the 1990s. They found three things about internees assigned to camps in wealthier areas:

- They were richer, more likely to complete college, and work in a high-status job. By 1980, the average family of an internee placed in the camp in the wealthiest region (Gila River, Arizona) earned 30% more than one sent to the poorest camp (Rohwer, Arkansas).

- Their children were more economically mobile. The income of children of internees in wealthier areas was less dependent on their parents’ incomes.

- They were more optimistic and felt greater agency. By the 1990s, internees placed in camps in wealthier areas were more likely to believe that “success is the best way to judge a man” and “if you try hard enough, you can get what you want,” based on a survey by the Japanese American Research Project. Their poorer-placed counterparts, by contrast, were more likely to say the “secret of happiness is not expecting too much out of life” and “it’s not fair to bring a child into this world.”

Shoag thinks these findings are relevant to today’s refugee crisis. His research challenges the policy of resettling immigrants and refugees to depressed areas, as many countries in Europe are now doing. While this influx could boost the local economy, it may also have consequences for the incomes and wellbeing of new residents and their children far into the future.