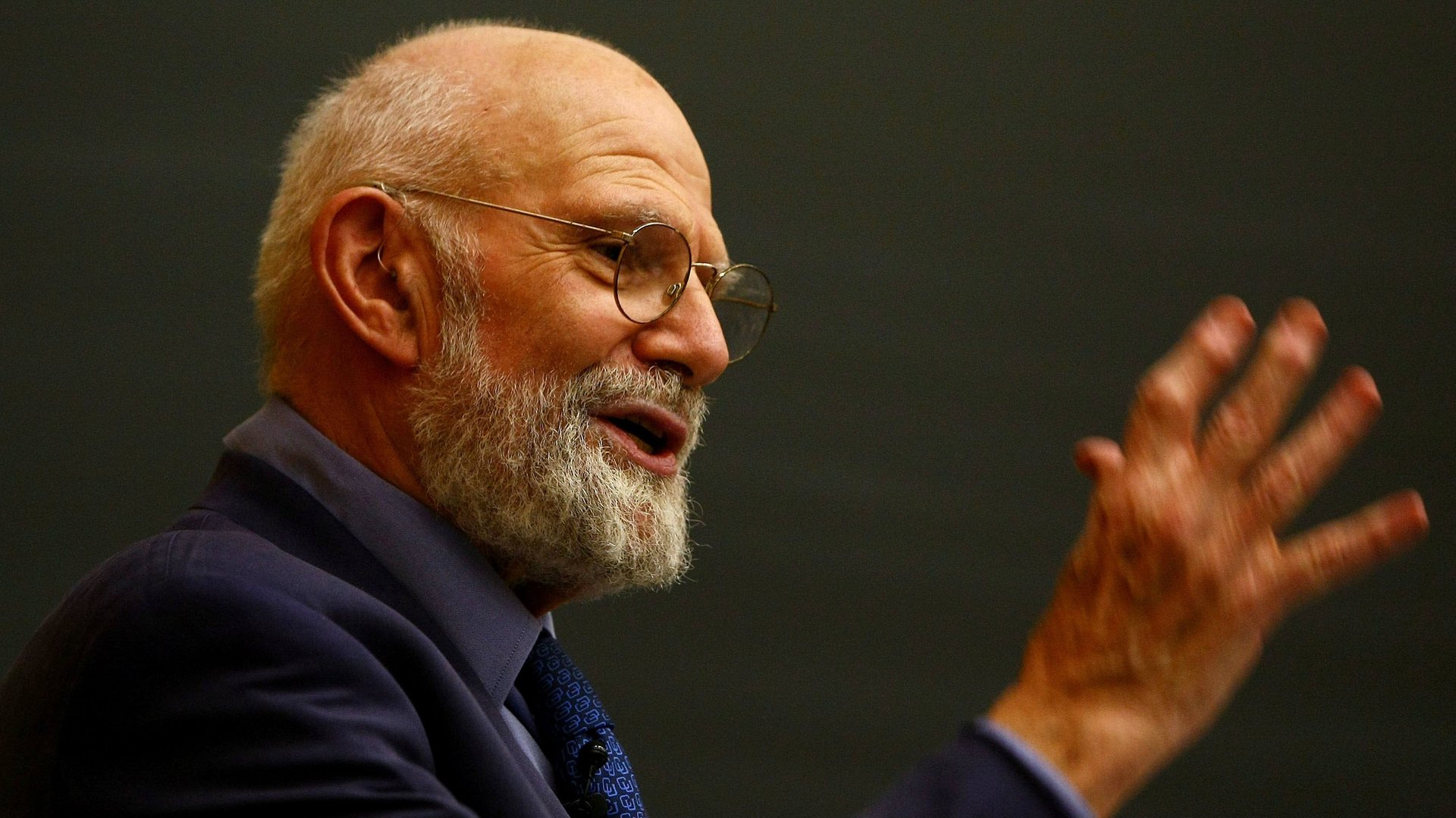

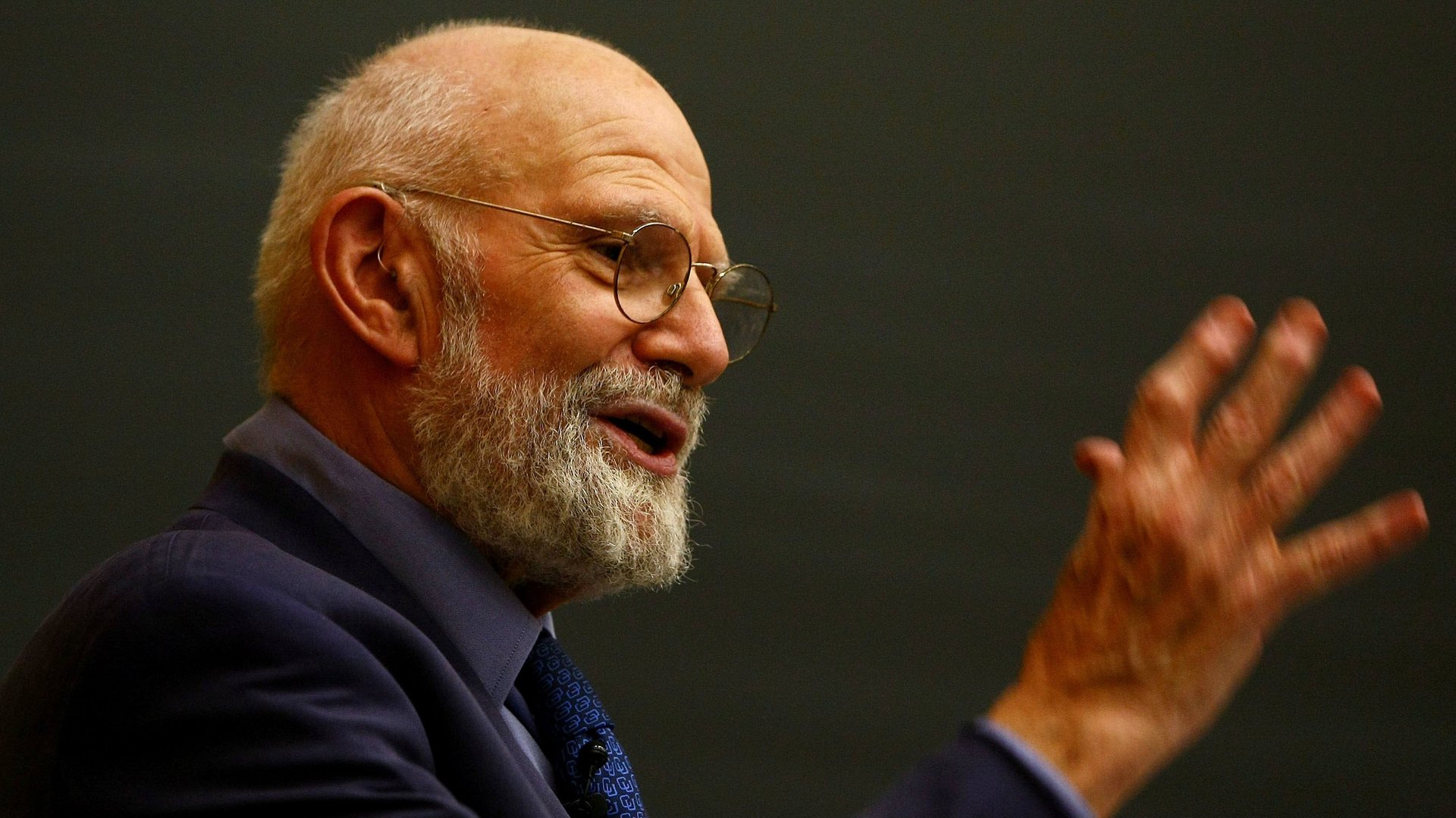

Oliver Sacks warned us against the dangers of obsessive hobbies

Most of us know Oliver Sacks for his best-selling books, which have sold well over a million copies. A practicing neurologist for most of his life, the New York Times called him “one of the great clinical writers of the 20th century” and “the poet laureate of medicine.”

Most of us know Oliver Sacks for his best-selling books, which have sold well over a million copies. A practicing neurologist for most of his life, the New York Times called him “one of the great clinical writers of the 20th century” and “the poet laureate of medicine.”

What most people don’t know is that Oliver Sacks was also an obsessive weightlifter. So obsessive, in fact, that he broke the California State record in his twenties — lifting an impressive 600 pounds.

Decades later, an older and wiser Oliver Sacks, body broken and scarred, would reflect on his weightlifting days. He wrote in his autobiography: “What fools we were…”

I read biographies because of what they teach me about how to live. They say the only way to learn is to get your hands dirty and make mistakes. But biographies let you cheat. Books let us live inside others, fail where they fail, and grow where they grow. So what can we learn from Oliver Sacks?

As a young man, Sacks the weightlifter found his moment of glory — a feature in a magazine, the approval of his peers, and the title of champion. But at what price?

Many years after his glorious moment, Sacks, crippled in a hospital bed, meets an old friend from his weightlifting days. He tells the story in his On the Move:

“I had pushed my quadriceps, in squatting, far beyond their natural limits, and this predisposed them to injury, and it was surely not unrelated to my mad squatting that I ruptured one quadriceps tendon in 1974 and the other in 1984. While I was in hospital in 1984, feeling sorry for myself, with a long cast on my leg, I had a visit from Dave Sheppard, mighty Dave, from Muscle Beach days. (Dave was a silver medalist at the 1956 Summer Olympics and set five world records in his career.) He hobbled into my room slowly and painfully; he had very severe arthritis in both hips and was awaiting total hip replacements. We looked at each other, our bodies half-destroyed by lifting. ‘What fools we were,’ Dave said. I nodded and agreed.”

It wasn’t just his legs.

“…I developed a pain in my lower back so intense that I could hardly move or breathe; I wondered if I had fractured a vertebra. Nothing amiss was seen on X-ray, and the pain and spasms resolved in a couple of days, but I was to have excruciating back attacks for the next forty years (they only let up, for some reason, when I was 65 or were then, perhaps, ‘replaced’ by sciatica).”

So that moment of glory cost Oliver Sacks 60 years of chronic, stabbing pain. Was it all worth it? Maybe.

Hobbies are great. But sometimes a hobby mutates into some else — an obsessive, all-consuming beast.

To break the state record, Sacks needed to move up several weight classes. He tells us of his “bulking” journey, again in On the Move:

“[Mount Zion Hospital’s] coffee shop offered double cheeseburgers and huge milk shakes, and these were free to residents and interns. Rationing myself to five double cheeseburgers and half a dozen milkshakes per evening and training hard, I bulked up swiftly, moving from the mid-heavy category (up to 198 pounds) to the heavy (up to 240 pounds) to the superheavy (no limit).”

Many times in my life, I’ve lost myself this way. For a year of my life, I devoted myself single-mindedly to the practice of the martial arts. I got off work at five, drove to the dojo, and would “roll” until midnight with the other students — the goal was to trap their joints or neck with powerful “submission” techniques.

Each night, I would drive home in a daze, mouth dry and vision blurred. Three months in, I started to walk with a limp. Six months in, I tore the cartilage in both my ears and they swelled up like Chinese dumplings — a classic case of “cauliflower ear.” There was not a day that my joints did not burn.

I was killing myself, but I didn’t care. Why did I go so far? When does a hobby — done for fun or to relax — become a neurotic obsession?

Sacks reflects:

“I sometimes wonder why I pushed myself so relentlessly in weight lifting. My motive, I think, was not an uncommon one; I was not the 98-pound weakling of bodybuilding advertisements, but I was timid, diffident, insecure, submissive. I became strong — very strong — with all my weight lifting but found that this did nothing for my character, which remained exactly the same.”

In those moments at the dojo, when I lost myself in the “flow”, there was no time to think of anything else. No time to think of work, no time to think of relationships. And, of course, no time to think of how lonely I was.

In Best American Essays, Jonathan Franzen writes:

“Kierkegaard, in Either/Or, makes fun of the “busy man” for whom busyness is a way of avoiding an honest self-reckoning. You might wake up in the night and realize that you’re lonely in your marriage, or that you need to think about what your carbon footprint is doing to the planet, but the next day you have a million little things to do, and the day after that you have another million things. As long as there’s no end of little things, you never have to stop and confront the bigger questions.”

Hobbies are wonderful things, but be careful lest they try to replace the irreplaceable—to supplant love with sex, friendship with fantasy, and meaning with madness.

This post originally appeared at Better Humans. Want more? Charles publishes The Open Circle, a free weekly newsletter.