The ideological battle dividing the world is perfectly illustrated by this fight over a Polish museum

Following last weekend’s events in Charlottesville, where a confrontation between a march of white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and counter-protesters turned violent, a long-standing debate surfaced over the difference between history and memory. Is tearing down Confederate monuments erasing history, like US president Donald Trump says? Or is it changing “how we remember history,” as one historian put it in the New York Times? A version of this debate is happening in other countries, in democracies that are going through similar battles over the shape of their identity. Memory easily becomes a weapon, wielded by two camps that are beyond the point of attempting dialogue.

Following last weekend’s events in Charlottesville, where a confrontation between a march of white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and counter-protesters turned violent, a long-standing debate surfaced over the difference between history and memory. Is tearing down Confederate monuments erasing history, like US president Donald Trump says? Or is it changing “how we remember history,” as one historian put it in the New York Times? A version of this debate is happening in other countries, in democracies that are going through similar battles over the shape of their identity. Memory easily becomes a weapon, wielded by two camps that are beyond the point of attempting dialogue.

Nowhere is this more evident than in Poland, where a heated political debate centers around not a monument, but a museum.

The Museum of World War II opened in March 2017 in Gdańsk, a seaside city where the first shots of the war were fired. Work on the structure and exhibits lasted nearly a decade. In the meantime, the country’s political situation was upended. Some Poles became politically apathetic, others disillusioned with the centrist government of Donald Tusk, who now serves as the president of the European Council. This allowed Law and Justice, a right-wing populist party boosted by the support of the Catholic church, to sweep in and win the 2015 presidential and parliamentary elections. The new political guard is not happy with the museum’s main exhibition, a comprehensive view of the war that focuses on the life and suffering of civilians all around the world. Law and Justice doesn’t think that the exhibit, which was commissioned by the previous government—its arch enemy—shows the most important aspect of the war: the unique quality of Polish martyrdom and heroism.

In many ways, the battle over the museum is just another front of a larger global ideological war. On one side, you have the universalists, armed with their globalism, liberalism, and concerns for human rights. On the other, you have the nationalists, wielding their exceptionalism, isolationism, and often conservative religious values. These two narratives clash as they try to define polarized nations and their place in the world.

In Poland, these visions are roughly represented by two groups: city-dwelling EU loyals versus the largely small-town “patriotic” crowds that enthusiastically greeted Donald Trump during a recent visit to the country. World War II is an unavoidable, inescapable presence in the country where it started, and it thoroughly devastated the nation. Both of these groups aim to make the war’s history their own, interpreting it in vastly different ways, and taking from it completely opposite lessons.

A global war…

The museum is massive. From the outside, it’s a lop-sided structure, jutting out of an

otherwise sparse square at a dramatic angle, designed to evoke a crumbling house. To enter, you descend below ground. The exhibition is centered on an axis that runs through the building, a high-vaulted hallway of sorts, lit by a stark stream of daylight down the middle.

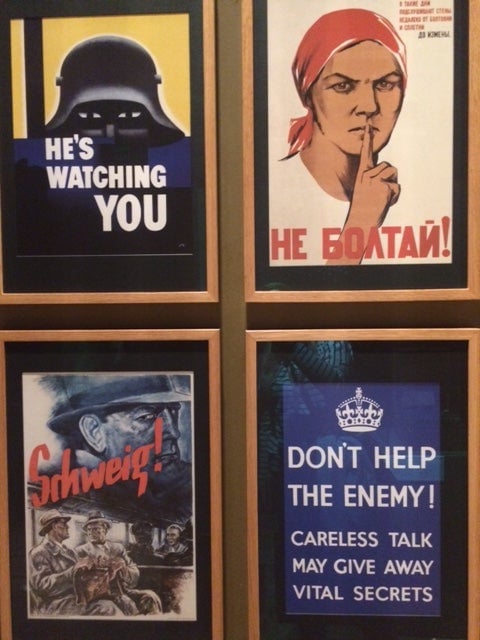

How the paths of totalitarian movements around the world co-existed and converged becomes evident through propaganda posters that scream at you from the first rooms of the exhibit, country by country: Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain. The graphics, colors, and content are often strikingly similar, reminding the viewer about the uniformity of supremacist and authoritarian ideas.

Later on in the exhibit, you’ll see photographic evidence of how lines to get strictly rationed food were long in both France and Russia, and you’ll be able to listen to the

upbeat music that helped people keep their spirits up in different countries. A list of pogroms and massacres of civilians shows not only the ones that are well known in Poland, but also of tragic events in Greece and the former Czechoslovakia.

The war affected everyone, from Croatians to Koreans. Even the Soviet Union, Poland’s number one enemy throughout the centuries, is shown with compassion in a chilling room about the siege of Leningrad, through which the eerie chants of Russian monks waft.

…or a globalist one?

Even before the museum opened, minister of culture Piotr Gliński, likely basing his criticisms on the opinions of two right-wing historians and a pundit that he commissioned, said that its character is too universalist (link in Polish), and that it does not highlight Polish suffering enough. Gliński’s experts, who only saw a 90-page description of the exhibit, complained that the Warsaw Uprising, the biggest single resistance effort against the Nazis during the war (which has its own massive museum in Warsaw), was virtually absent, as were the pogroms of Poles by Ukrainian nationalists. Historian and Law and Justice senator Jan Żaryn, in his critique, described on Gdańsk’s official city website, said that creators of the exhibit introduced a “leftist-liberal narrative.” He unabashedly went after the gut-wrenching section on hunger in Jewish ghettos, seemingly trying to say it wasn’t anything unique—that Poles experienced hunger as well.

It’s difficult to see this criticism as valid. The museum is filled with examples of Polish suffering and the nation’s valiant spirit. You can learn both about the Uprising and the pogroms. There’s a powerful room on the Katyń massacre, where the Soviet secret service murdered thousands of Polish military officers, and there’s a separate section for the Nazi Enigma coding machine that the Poles helped crack. The museum is, after all, in Poland, and it’s from a Polish perspective—it’s just not in your face.

Gliński wanted to merge the museum with another institution he was planning, which would focus on the first days of the war and on the plight of the Poles. This sparked widespread outcry, including from top foreign historians who collaborated on the museum’s exhibit, who said the merger was simply a ploy to gain control of the project. Despite this, a court sided with the government in April (paywall).

Many are concerned about potential censorship in the museum, changes that would comply with a politicized version of history embraced by the right-wing government, the so-called “politics of memory (paywall).” The way this policy now functions in Poland often enters whitewashing territory.

One example is a decision from the Polish state-run television to precede the broadcast of the Oscar-winning film Ida with a 12-minute program that warns about historical “inaccuracies,” including an overly critical portrayal of Poles in relation to the country’s Jewish population during the Nazi occupation. Norman Davies, one of the most preeminent historians studying Poland abroad, calls current-day “politics of memory” in Poland “a xenophobic attempt to re-write history” in an interview with The Observer.

Averting one’s eyes from a global and multicultural point of view is of course a theme du jour among the world’s populists—this is, in part, how the US got Trump and Charlottesville, the UK got Brexit, and France came close to getting Marine LePen as president. (The latter has used very similar “politics of memory” tactics by denying the French role in the infamous Vel d’Hiv roundup of Jews who were later sent to their deaths.)

An attempt to quash a narrative of World War II that puts emphasis on its international character is in a way just another proxy for standing against the forces of globalization. In Poland those forces are most immediately represented by the European Union, whose sanction mechanisms have become virtually the only threat to Law and Justice’s power.

If you look away from the global character of war, you can’t make connections between the war in Syria and what happened to Poland during World War II—which the museum quite literally attempts, showing images of Syrian refugees in a film that concludes the exhibit. It recounts the post-war history of the world, still filled with armed conflict. Once you decide to ignore these links, it’s much easier to refuse letting in refugees to the country, something the Polish government has been adamant about. The Museum’s current director, appointed by Law and Justice, is not a fan of this film, which he says is confusing (link in Polish).

War is bad—or not?

A large space in the museum is devoted to the military, where history nerds of a certain

kind lean over glass cases to scrutinize models of ships and planes. A huge, life-size aircraft hangs from the ceiling, creating the impression that you’re about to get hit by Nazi fire. But while the museum has two actual tanks, you’d be hard-pressed to find extensive discussion of strategy or tactics, battle plans and maps. It’s not the institution’s focus. Even the military exhibit homes in on the individual, human experience of being a soldier, displaying tiny treasures such as 1940s condoms, covered by innocent illustrations that look quaint today, and the meticulous engravings on privates’ metal canteens.

The museum is full of such small examples of coping with the overwhelming reality of war. There are recipes that helped people make the best of the ersatz products available in war-ravaged stores, and my favorite object was a wedding dress made out of a Japanese parachute that an American army engineer brought back for his bride at a time when silk was a rare commodity. Human resilience is an important part of the exhibit—but so is the war’s tragedy. The wedding dress is in the museum’s central hallway, at the exit of a room that features a documentary about Korean comfort women, and at the entrance of a space dominated by a train car* like those used to transport Jews to Nazi concentration camps.

Another conservative historian who reviewed plans of the museum said that the “most appropriate summary of the [museum’s] message is a phrase used in Poland during communism: ‘War—never again!’” His statement is meant to be derogatory because of its association with a dark period in Polish history. War, he continues, “hardens man, shows his most noble intentions, patriotism, civic duty, and sacrifice for others.” In other words—he believes it’s just not right that the main message of a World War II museum should be: “War is bad.”

For some, this sentiment will be astonishing. It did raise controversy among some Polish observers. But it will be perfectly on point for others. It’s hard to imagine that the master ideologue and architect behind Donald Trump’s populist appeal, the just-deposed Steve Bannon, would disagree, considering his obsession with war. After all, in a documentary that Bannon directed and wrote, the generation that was shaped by the hardships of World War II and the Great Depression emerges as far superior to the one of its children, baby boomers who eschewed traditional American values and destroyed the country.

In this general view, war is defined not by the millions of murdered civilians and conscripts or by all-encompassing destruction—it’s defined by the tough, noble, patriotic ideal of a warrior.

Always fighting the enemy

There is, of course, a much more mundane explanation of the battle over the museum. Jarosław Kaczyński, the head of Law and Justice and the puppet master behind its every political move, has said that the institution is “Donald Tusk’s gift for Angela Merkel, serving Germany’s politics of history.” Merkel is a stand in for the historical enemy, now a shining example of a European success story. Tusk, one of Gdańsk’s most famous sons, is his arch enemy, exemplifying the image of Poland that is the opposite of Kaczyński’s: European, liberal, with capitalist, elite values.

That’s a crucial reason for why Kaczyński and his party hate the museum so much: A certain fixation on the previous political guard is an indispensable ingredient of populist rule, one we see frequently in America: Trump can’t seem to stop talking about his former opponent Hillary Clinton, and he is obsessed with his predecessor Barack Obama. It’s always easier to function in campaign mode; it’s simpler to rally-up the crowd if there’s an enemy to point to, than to actually do the work of governing.

But the events in Charlottesville, and those images of Syrian refugees, projected on a wall of a museum in Poland, further remind us that politics of global history—or memory—are as important, perhaps more important, today, as have ever been before.

All of the photos in the story are taken by the author.

*Note: An earlier version of this article stated that a replica train car was on exhibit in the museum. In fact the exhibit is of an actual train car used during World War Two.