What a five-star hotel’s pool pee problems say about Shenzhen’s water shortage crisis

When temperatures in the southern megacity of Shenzhen hover around 90 degrees this time of year, people head to outdoor swimming pools in droves. But they might want to consider a drier way to cool off. Recent tests by Shenzhen authorities found that 14 out of 140 pools had overly high levels of bacteria, chlorine and urine.

When temperatures in the southern megacity of Shenzhen hover around 90 degrees this time of year, people head to outdoor swimming pools in droves. But they might want to consider a drier way to cool off. Recent tests by Shenzhen authorities found that 14 out of 140 pools had overly high levels of bacteria, chlorine and urine.

The fanciest pool in the city—that of the five-star St. Regis Hotel—failed the last of those tests, reports the Economic Observer Online (link in Chinese).

Too much urine in your pool is a tougher problem to solve than you might think. Urea, which can be harmful if swallowed, can be cleaned up with chlorine; but simply upping the chlorine levels can hurt swimmers’ skin. And it’s probably hard to enforce bladder control among the children of well-heeled patrons (or the patrons themselves—research suggests adults relieve themselves in swimming pools too).

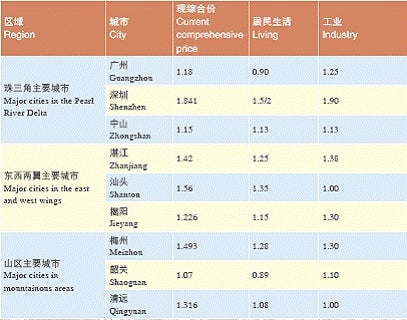

The St Regis did one of the only things that you can do combat the effects of rampant pool-peeing. After the results were published, it boosted the water in circulation from 1 ton (0.97 tonnes) per day to 4 tons a day. That has to be pricey—especially in Shenzhen. Water supplies are so low that its water prices are the highest in the area, which might be why even luxury hotels are scrimping:

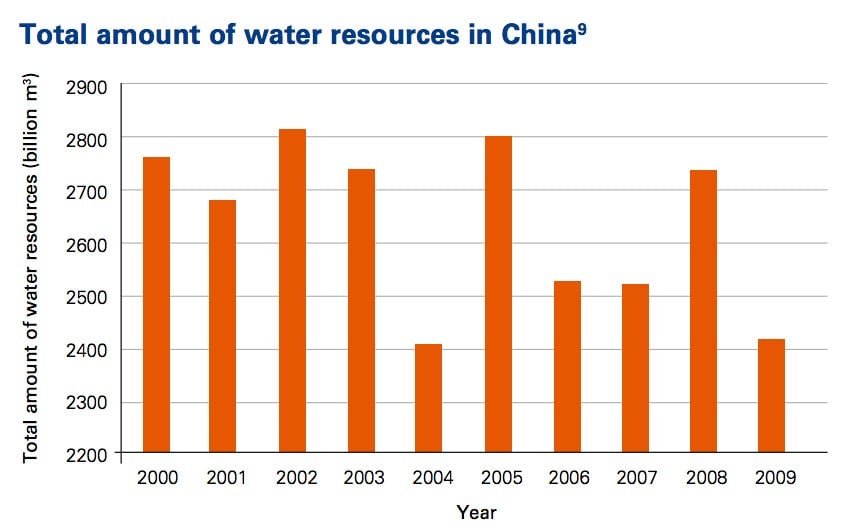

China’s water supply is drying up fast outside Shenzhen, too, thanks to pollution, population growth and geography:

But Shenzhen’s water woes are unusually bad.

The city’s available water supply was only 20% of the Guangdong average (paywall), and 25% of the national average, a research scientist told the South China Morning Post.

In a 2011 study, Hong Kong think tank Civic Exchange found that Shenzhen is already using 14% more water than it should. The research estimated that by 2020, the city would face acute water shortages. Already last year, a drought left Shenzhen’s surrounding villages without water for almost three weeks.

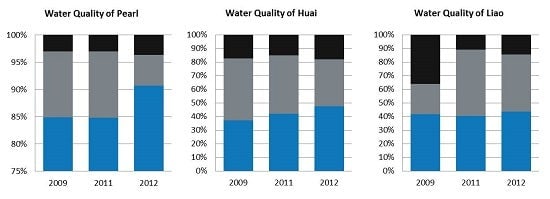

Shenzhen’s dire straights have to do with being picked as a “special economic zone” open to foreign investment and trade back in 1979, when Shenzhen was only a sleepy fishing village. Plans for its development only envisioned supporting about 1 million people, according to the SCMP report. Today its population is more than 10 million. Also, the city is located on a river estuary, where pollution is unusually high, while the nearby sections of the heavily contaminated Pearl River are getting worse:

There are signs that the Chinese government is getting serious about cleaning up its water supply. For example, Guangdong’s provincial government just reported to the local legislature that 28% of soil in the Pearl River Delta was polluted by heavy metals—the first official admission of its kind. Water pollution and scarcity already shaving off 2.3% of China’s GDP each year, according to World Bank estimates, which makes the reforms even more pressing. In the meantime, don’t open your mouth in a Shenzhen swimming pool.