571 words on exactly why boxing should be banned

When Muhammad Ali turned 30, his speech began to slow. By 1978—when Ali was 36, and three years before he retired—he was slurring his words. According to a new study by scientists at Arizona State University, his speech rate slowed 26% in that time period (an ordinary adult would see little or no decline whatsoever). The researchers say it was almost certainly due to the violence of the boxing ring: “The more punches he took, the more steeply his speaking abilities declined,” they write (paywall).

When Muhammad Ali turned 30, his speech began to slow. By 1978—when Ali was 36, and three years before he retired—he was slurring his words. According to a new study by scientists at Arizona State University, his speech rate slowed 26% in that time period (an ordinary adult would see little or no decline whatsoever). The researchers say it was almost certainly due to the violence of the boxing ring: “The more punches he took, the more steeply his speaking abilities declined,” they write (paywall).

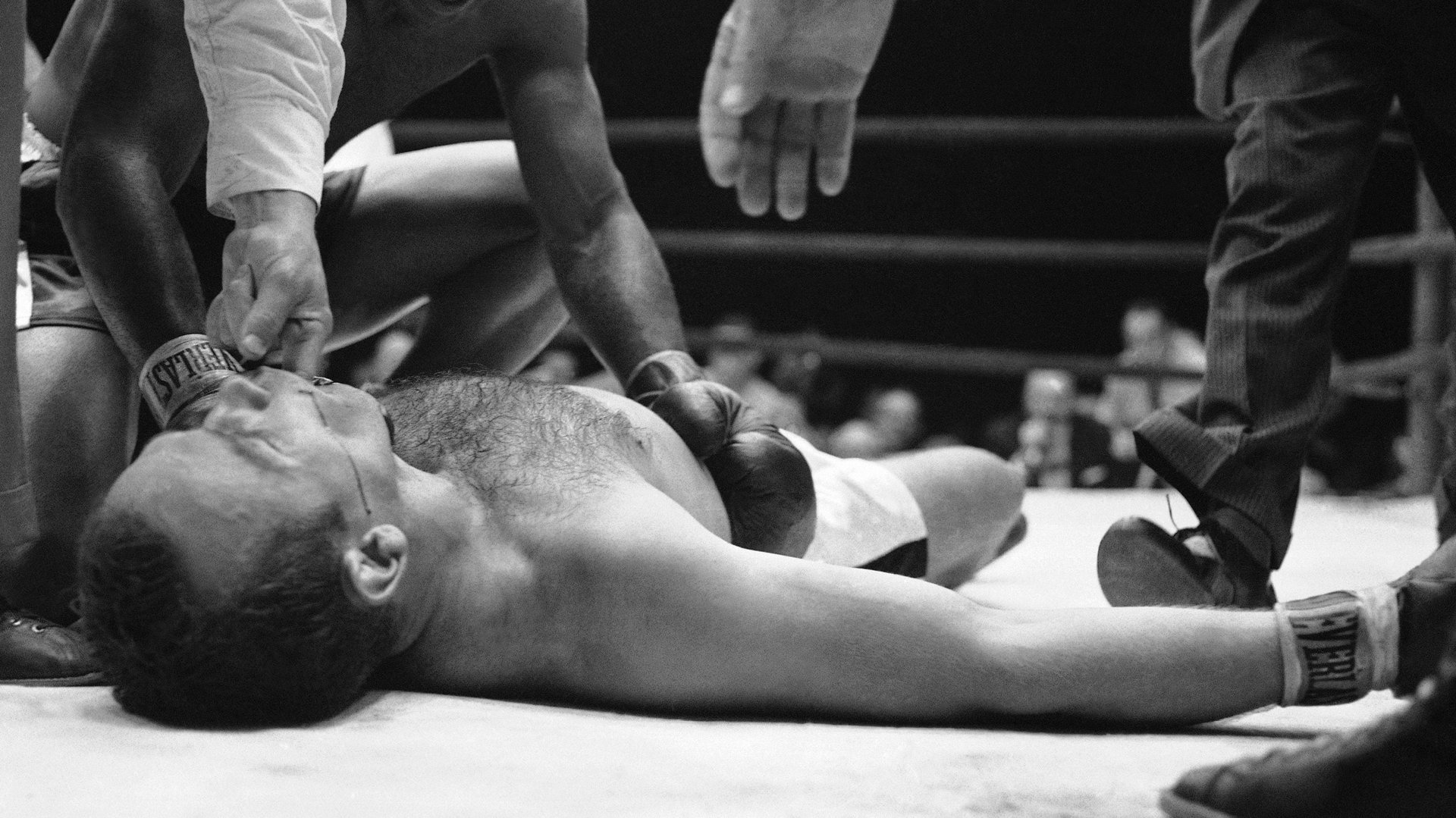

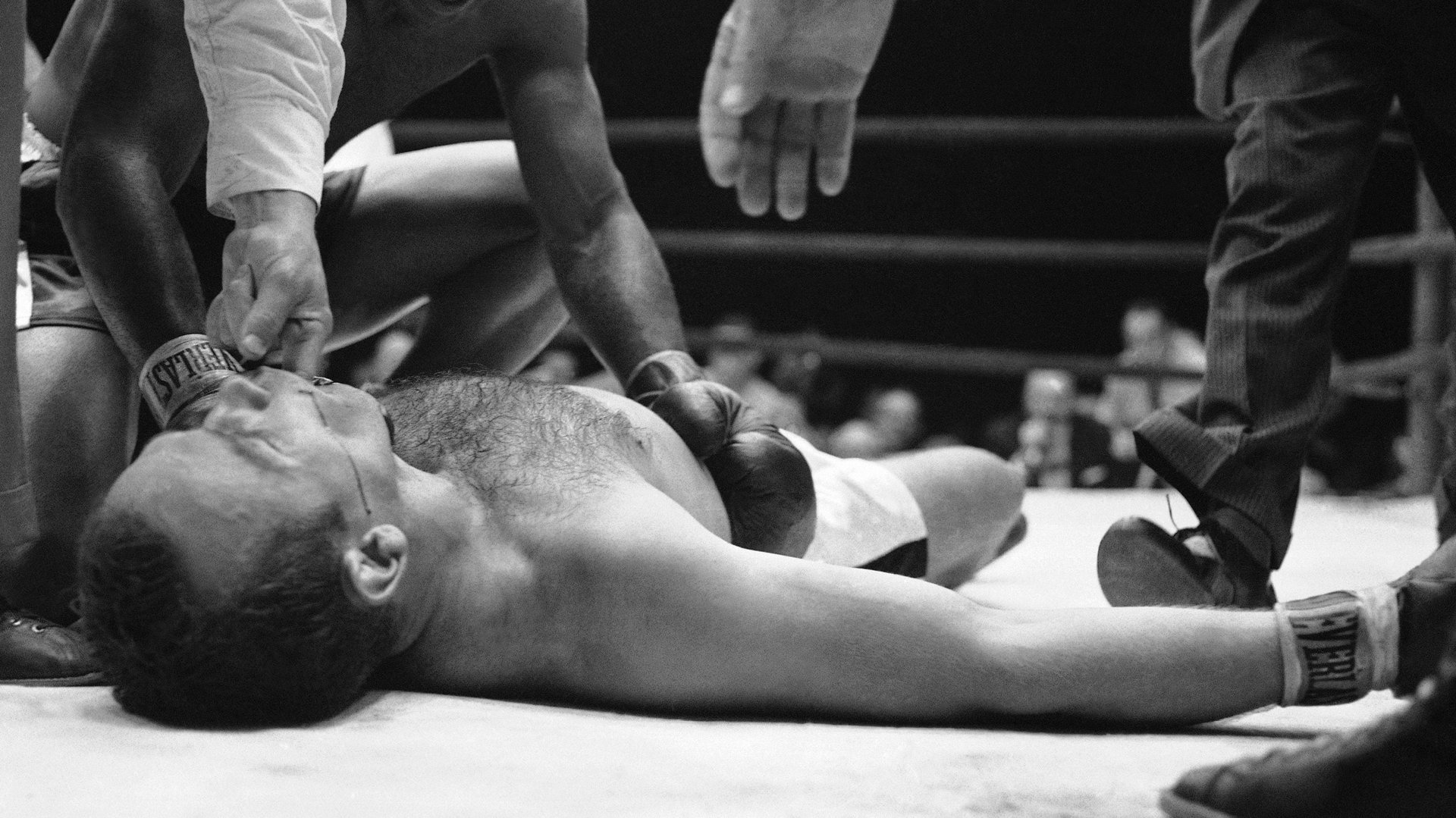

Ali is considered one of best boxers of all time, and had a graceful style of feinting, dipping, and ducking that often kept him from sustaining the hardest hits to the head. All he got was long-term brain damage. The less transcendent are not so lucky. Just two months ago, boxer and mixed martial artist Tim Hague died after sustaining a traumatic brain injury in a fight. And if you think boxing is more elegant than MMA, think again. A 2015 study found that boxers are more likely than MMA fighters to lose brain volume and processing speed to head trauma. Prichard Colon, now 24, remains in a persistent vegetative state after a 2015 fight in which the former boxer kept telling his ringside doctor he was dizzy but was made to go on until the end of the bout.

These stories are not new; people have been dying and been made debilitated in the boxing ring since the “sport” was invented. But for years, they were mostly ignored. When World War II broke out, the US loved boxing; it was second in popularity only to baseball among all spectator sports. Through the 1990s, boxing held the popular imagination of the country, with Mike Tyson and Evander Holyfield putting on massive shows for massive audiences and massive purses.

Even now, despite a vastly improved understanding of how the human brain functions, and how it can be destroyed by repeated trauma, we are still obsessed with these gruesome displays.

Tonight (Aug. 26), Floyd Mayweather and Conor McGregor will beat each other in front of some 20,000 people who paid on average $3,500 for the honor to sit in the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas. The front rows will be filled with famous athletes, entertainers, and politicians, displayed in all their finery. A predicted 4.75 million people around the world will pay $99 (HD quality) or $89 (standard) to see the fight on pay-per-view, and millions more will watch on friends’ TVs. Add in merchandise and other auxiliary sales, and estimates of the total gross of the fight go as high as $1 billion.

There are lots of bad ways to spend money, but bolstering a cultural artifact that should have and could have been eradicated years ago is one of the worst. Other sports like rugby, hockey, and especially American football have serious health risks too, of course, but boxing is the only one designed with the express purpose of causing brain damage. Football desperately needs to change, but brain injuries are a byproduct of tackling, not their explicit goal. In some cases, the winner of a pro boxing match is determined by judges awarding points, but ultimately the goal of the sport is to knock out your opponent, and that means anyone who steps into the ring is literally trying to produce a traumatic brain injury in another human.

Take away what makes boxing deadly and demeaning, and you’re left with nothing. And that’d be a good thing.