Nike is investing in robots that use static electricity to put its shoes together

While robots are already an established part of the manufacturing process for cars, electronics, and semiconductors, they have been much slower to take over production of sneakers and clothes.

While robots are already an established part of the manufacturing process for cars, electronics, and semiconductors, they have been much slower to take over production of sneakers and clothes.

One of the main reasons is that robots have a hard time handling the wide variety of soft materials used to make complicated products like a pair of sneakers. A Nike shoe can have as many as 40 different materials in its upper alone, all of which need to be precisely stacked and fused together to make the shoe. This is quite different from a cellphone plant or automotive factory, for example, where the materials involved tend to be rigid and fairly uniform, and robots can pick things up using a vacuum, magnet, or mechanical pincher.

In garment and shoe manufacturing, no single method has offered an ideal solution. A vacuum may pick up pieces of leather, but it can’t deal with mesh. Mechanical pinchers fumble with pieces that have different degrees of flexibility and stickiness. Magnets, while great for handling metal, are useless when it comes to fabric.

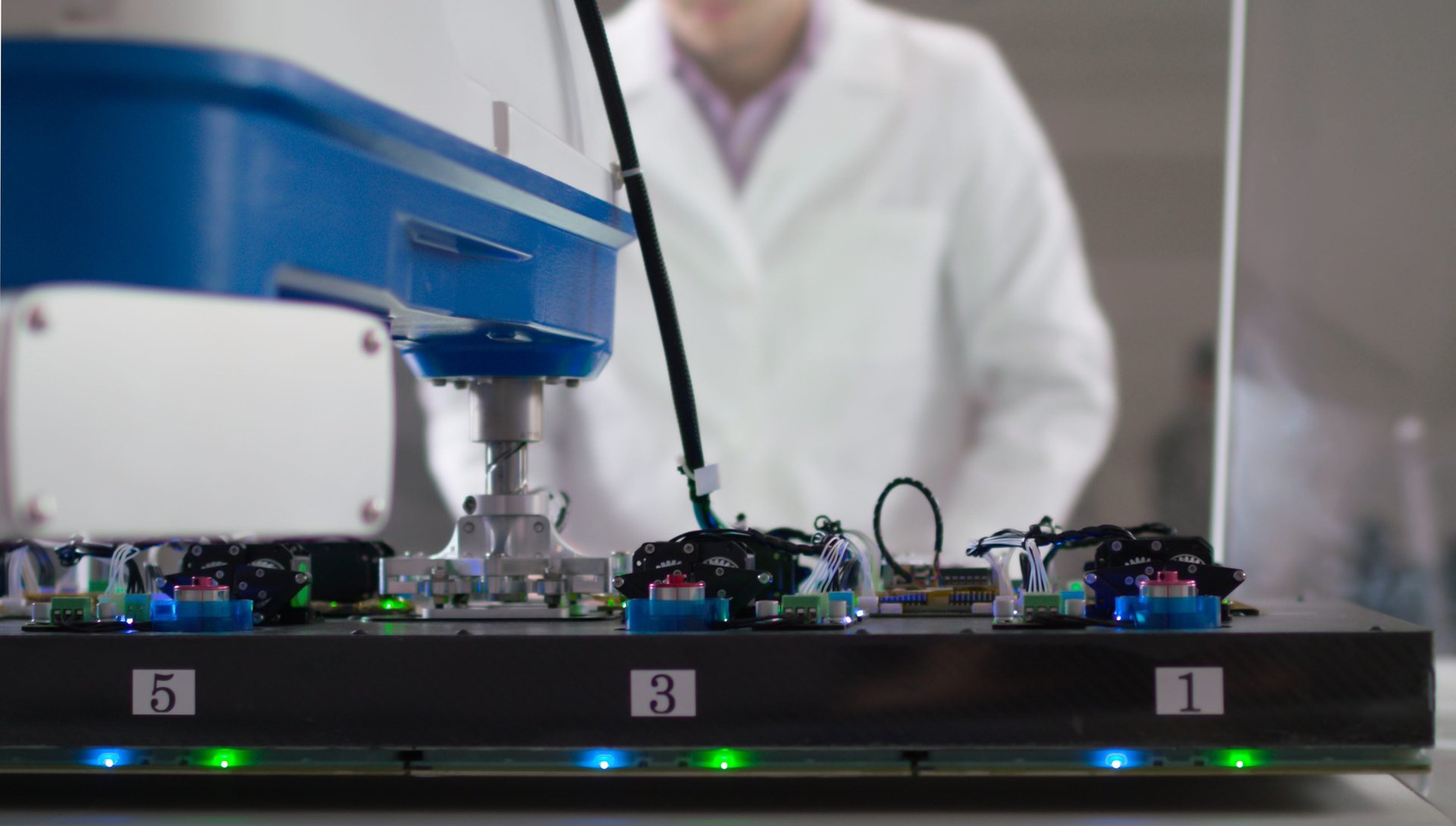

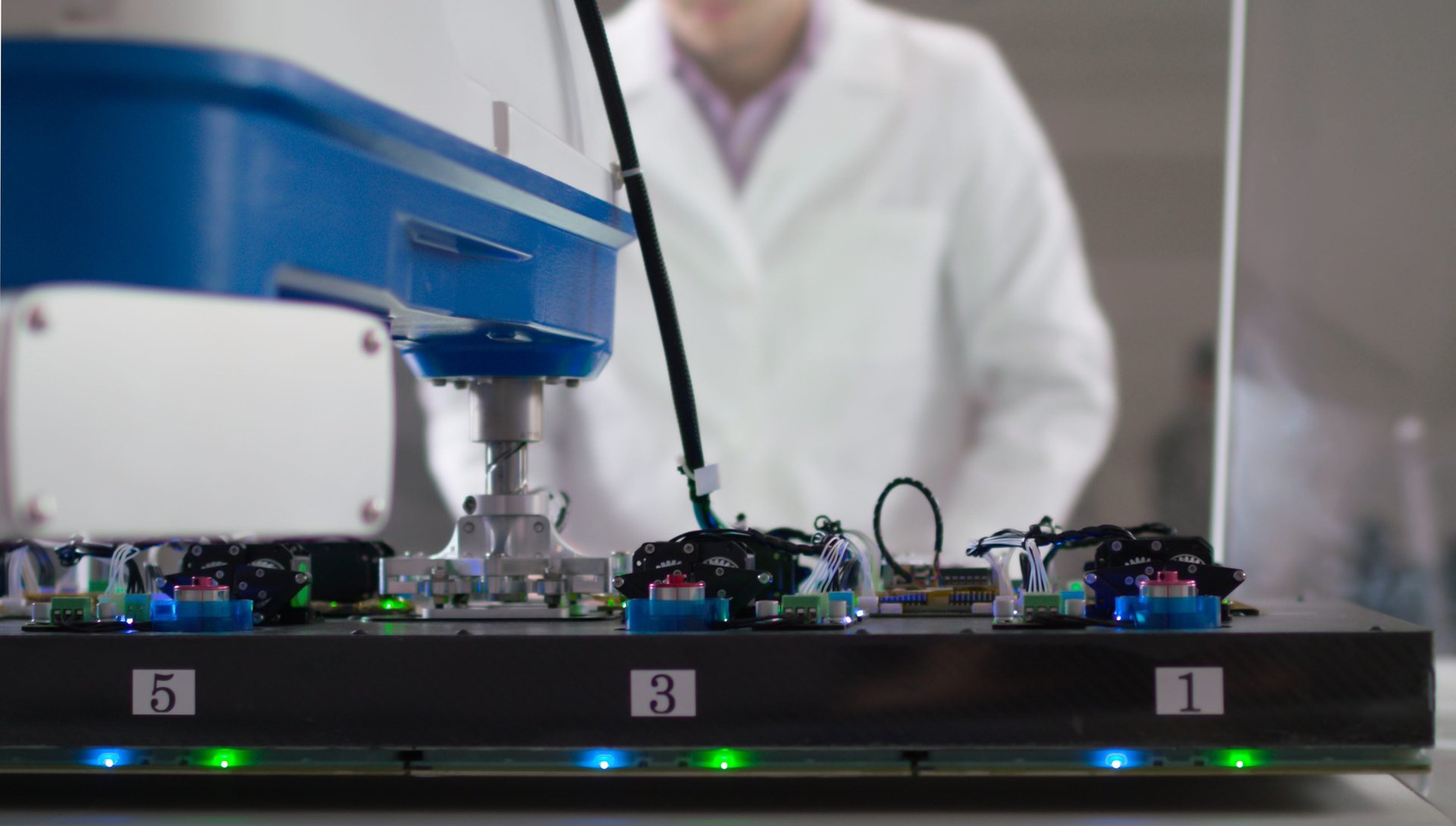

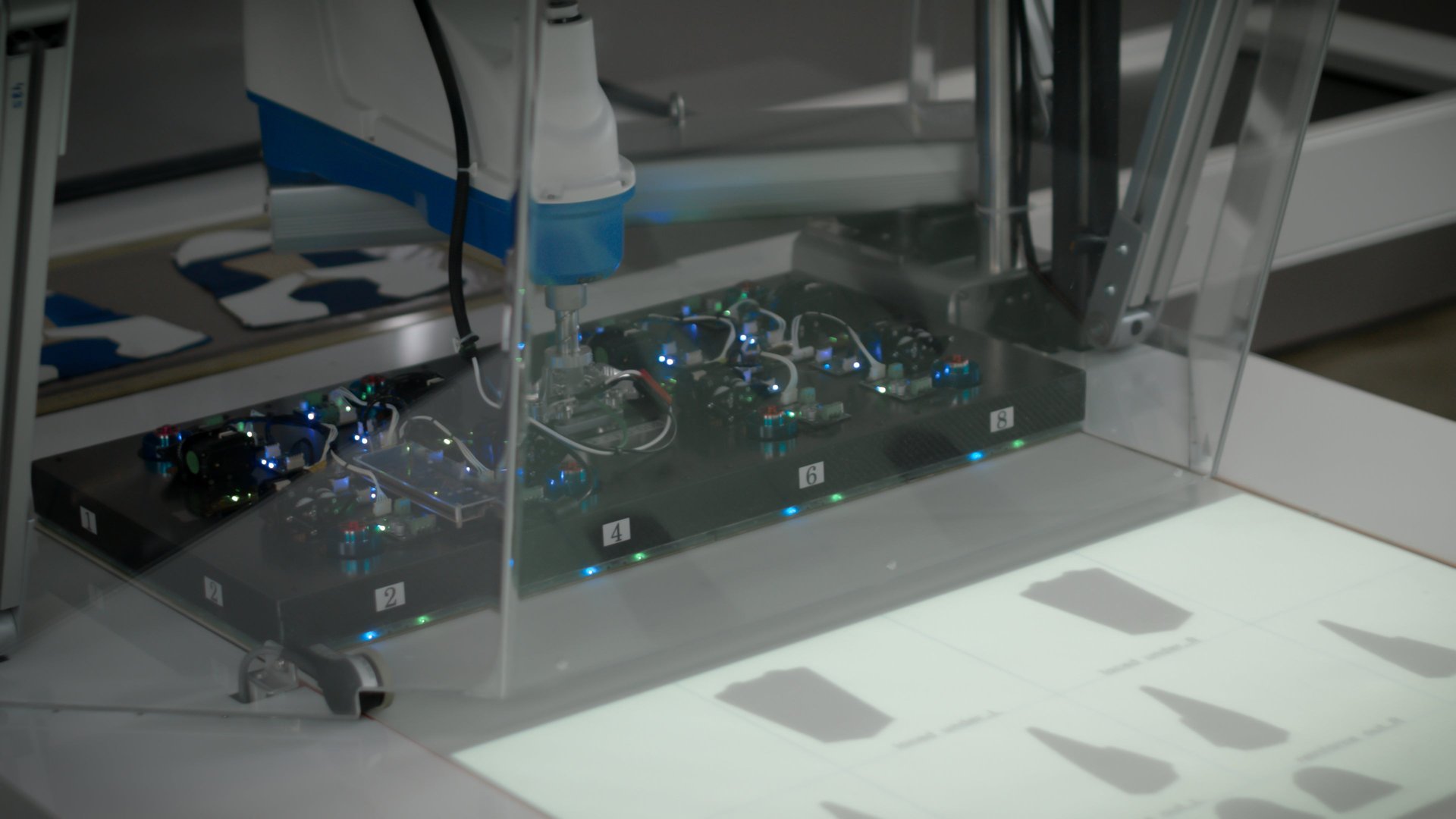

A California company called Grabit has a novel technology that’s solving this problem for Nike, and soon perhaps a number of clothes manufacturers as well. Grabit uses electroadhesion—basically the cling of static electricity—to let robots pick up and handle objects of all kinds. The company says the same technology is capable of maneuvering an egg, soft fabric, or a 50 lb. box.

The firm has Nike convinced. The sneaker giant acquired a minority stake in it a few years back. Now, as Bloomberg reported, Nike is installing about a dozen of its machines in factories making its shoes in Mexico and China. These Stackit robots, which are designed for stacking fabric, can precisely position all the pieces of a sneaker upper in 50 to 75 seconds. A human worker, by contrast, can take well over 10 minutes to do the same job.

“We’re just able to pick up multiple pieces at a time and put them down in the right place, based on the vision system and the robot operating system that we’ve designed,” explains Greg Miller, Grabit’s CEO. The human has to pick up and stack each piece individually.

Miller says that, in addition to Nike, a number of apparel companies are interested in the technology, particularly shirt makers. Esquel Group, a massive dress-shirt manufacturer that produces for companies including Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger, and Nike, is also an investor. “We’re working with them and a number of others in this space,” Miller says. “We’ve had discussions with Brooks Brothers, those sorts of folks.”

The technology is useful for making stiff shirt collars and cuffs, which like the upper of a Nike sneaker, have different layers that need to be stacked and then fused. Grabit plans to introduce robots that can do collars and cuffs next year.

The machines are a major investment, at more than $100,000 a piece according to Bloomberg, but their efficiency and long-term savings could let companies bring some manufacturing back to Europe and North America to produce goods for those markets. Higher worker wages in wealthier countries make automation the most viable way to produce clothes, which until now has relied heavily on low-wage workers in poorer countries.