Gold toilets, teen nose jobs, and the other things people buy in place of real social mobility

For 25 years, photojournalist Lauren Greenfield has traveled the US and the world documenting what she calls “the influence of affluence”: a culture-wide aspiration to wealth that, fueled by mass media, only seems to deepen as social mobility stalls.

For 25 years, photojournalist Lauren Greenfield has traveled the US and the world documenting what she calls “the influence of affluence”: a culture-wide aspiration to wealth that, fueled by mass media, only seems to deepen as social mobility stalls.

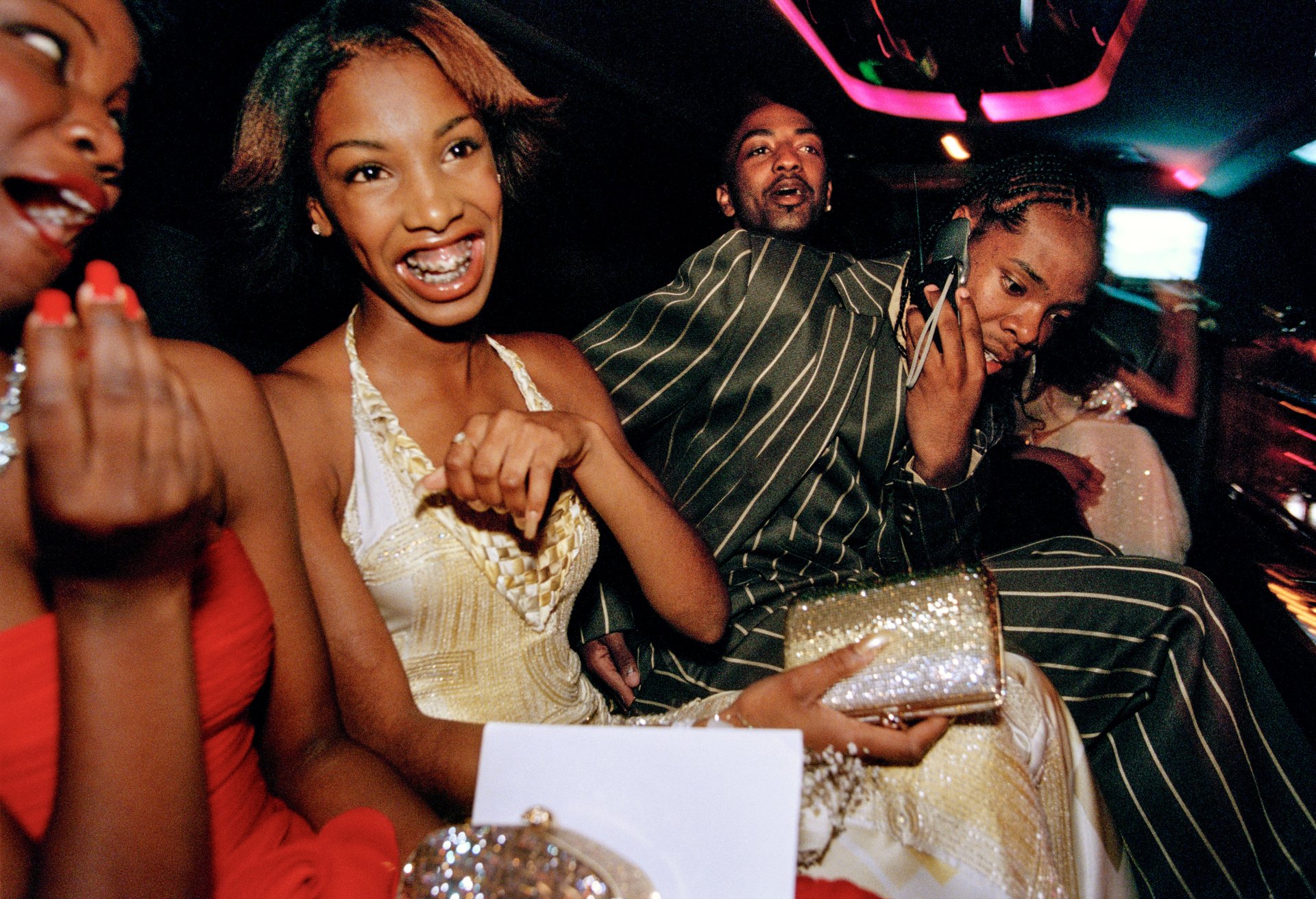

Greenfield and her camera have captured the glittering and grim elements of a society fixated on conspicuous consumption. Her subjects—raining dollars at strip clubs, oligarchs’ wives, houses shuttered and abandoned in the wake of the financial crash—are familiar images, rendered here as cultural artifact.

“The trends and behavior and attitudes that she’s depicting . . . are in many ways the dominant trend of our culture for this period from 1980 to the crash,” sociologist Juliet Schor told Quartz.

Greenfield’s photographs are collected in a book and traveling photography exhibition entitled Generation Wealth. Together, the photographs offer visual evidence of what Schor describes in the book’s preface as the defining social principle behind consumption: “What we want is determined by the social worlds in which we live.”

The exhibit concluded a run in Los Angeles in August and opens Sept. 20 at New York’s ICP Museum. Quartz spoke to Greenfield about consumption, aspiration, and what we lost by keeping up with the Kardashians.

Quartz: You started the project photographing young people in Los Angeles in the early 1990s. Did the trends that you document originate in Los Angeles, or was LA just one of many places where this attitude toward materialism was forming?

Lauren Greenfield: A lot of the drivers behind the trends come from the media, so starting with the kids growing up in LA felt like being close to the flame. It was a place where you could see the extreme manifestations of what was happening all over.

Going back and looking at these 25 years in retrospect, it was really interesting to see, for example, [a photograph of] Kim Kardashian at 12 at one of the parties. It was not a picture that was even in my original edit, because she was insignificant then. But Keeping Up With the Kardashians has been in a way a touchstone for the work, and her fame and rise has been symbolic for the work. So the fact that she was a kid here, growing up at that time, was significant to me.

The other thing I saw as beginning these changes were the Reagan ‘80s. The idea at that time that having money was good, and maybe even [meant] that you were a good person. Oliver Stone created Wall Street, and this character Gordon Gekko, who was intended as a villain ended up, ironically, becoming a role model to a generation on Wall Street, many of whom are in this book.

Those two things [were significant]. [You had] the inundation of media that started with MTV and exploded to all the cable channels, the internet, and social media, and with that the explosion of marketing going directly to the most vulnerable: kids, girls. And then the ethos in the air from the Reagan ‘80s and this shift from a more idealistic, socially minded view from the ‘60s and ‘70s to money becoming more important in the 80s.

Much of your work focuses on the things people buy in place of real social mobility. Can you talk more about the significance of conspicuous consumption as equality and mobility decline?

The backdrop to people prizing bling and “fake it to you make it” so much is that we have less social mobility we had in the 70s—progressively less—and more concentration of wealth in the hands of the few.

For a lot of people, the traditional American dream does not feel in reach. . . . This idea of meritocracy, that if you work hard you can be successful, is not within reach for a lot of people. I think it’s [the social critic]Chris Hedges who says that this kind of fictitious social mobility is the only social mobility that feels real.

I was so influenced by Juliet Schor’s view that our reference group has changed. We used to compare ourselves against our neighbors who lived in our community and aspired to the person who had the slightly better model home down the road, or the slightly better model car. Now we spend more time with people we know on TV than our neighbors, and we want what they have.

Even though the 1% is a small group, it’s constantly thrown in everybody’s face because the images are so ubiquitous in the media. There’s what Schor calls an “aspirational gap,” where keeping up with the Joneses has literally become Keeping Up With the Kardashians. We want what they have, and there’s no way where the traditional avenue of hard work and doing a little bit better than your parents is going to get you to Kardashian level. That’s fantasy land.

The publication of this project coincides with the early days of the Trump presidency. How does Trump fit with the cultural shifts you’ve documented?

[The Trump presidency] felt like an expression of all of the things I had been documenting: People valuing money, and monetary success being considered an indication of character and achievement. This idea of “fake it ‘til you make it”: you can have somebody with no experience in the job. The importance of celebrity: a reality star being able to leverage that into the highest public office in the land

The rise of narcissism. Really changing the idea of public service: helping people less fortunate doesn’t seem like part of the equation. In a way, the values of capitalism undermining the values of democracy.

And then on the gender side, I was really struck also by the connections: beautiful women being an expression of success, making money from the commodification of the body with the beauty pageant business. . . . I could not have predicted it, but I felt like the work shows the culture that gave rise to it.