At the world’s largest hedge fund, 24-year-olds use “dots” to critique their CEO

A week after Donald Trump was elected US president, the research team at Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, held a meeting to discuss what a Trump presidency would mean for the US economy.

A week after Donald Trump was elected US president, the research team at Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, held a meeting to discuss what a Trump presidency would mean for the US economy.

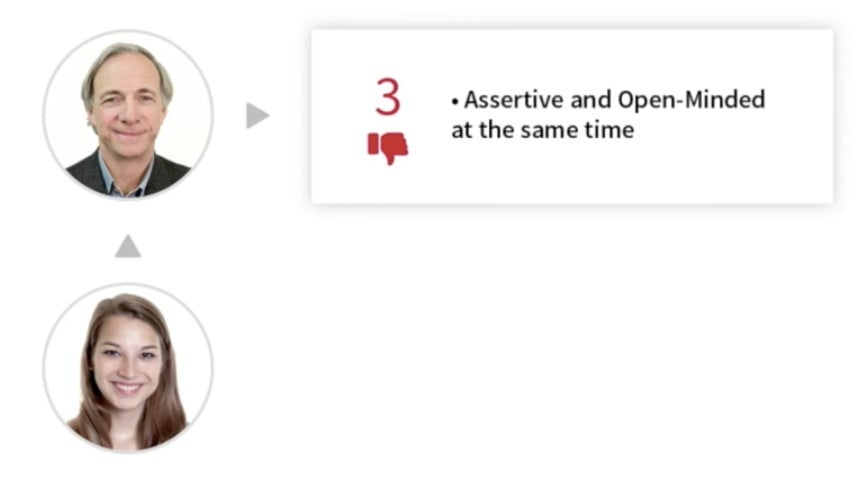

Ray Dalio, Bridgewater’s CEO and founder, and one of the 100 wealthiest people on the planet, led that meeting. Jen, a 24-year-old Bridgewater employee, thought Dalio’s performance was trash. So she told him so—with a “dot.”

Dalio told this story at a recent TED Talk in which he revealed ”The Dot Collector,” one of the tools Bridgewater uses to facilitate its infamous culture of “radical transparency.”

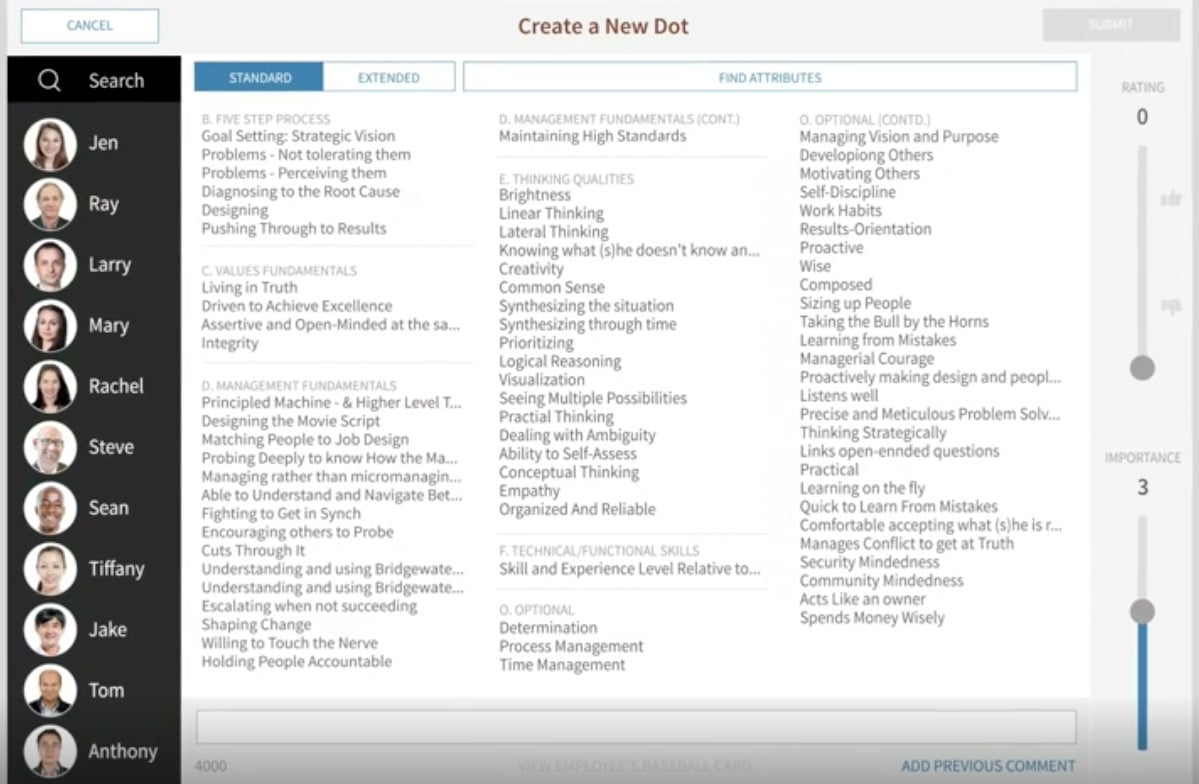

The Dot Collector app is installed on every Bridgewater employee’s proprietary iPad. Employees are expected to bring this iPad to every meeting, to give and receive constant feedback in the form of “dots.” Every dot you give and receive is public.

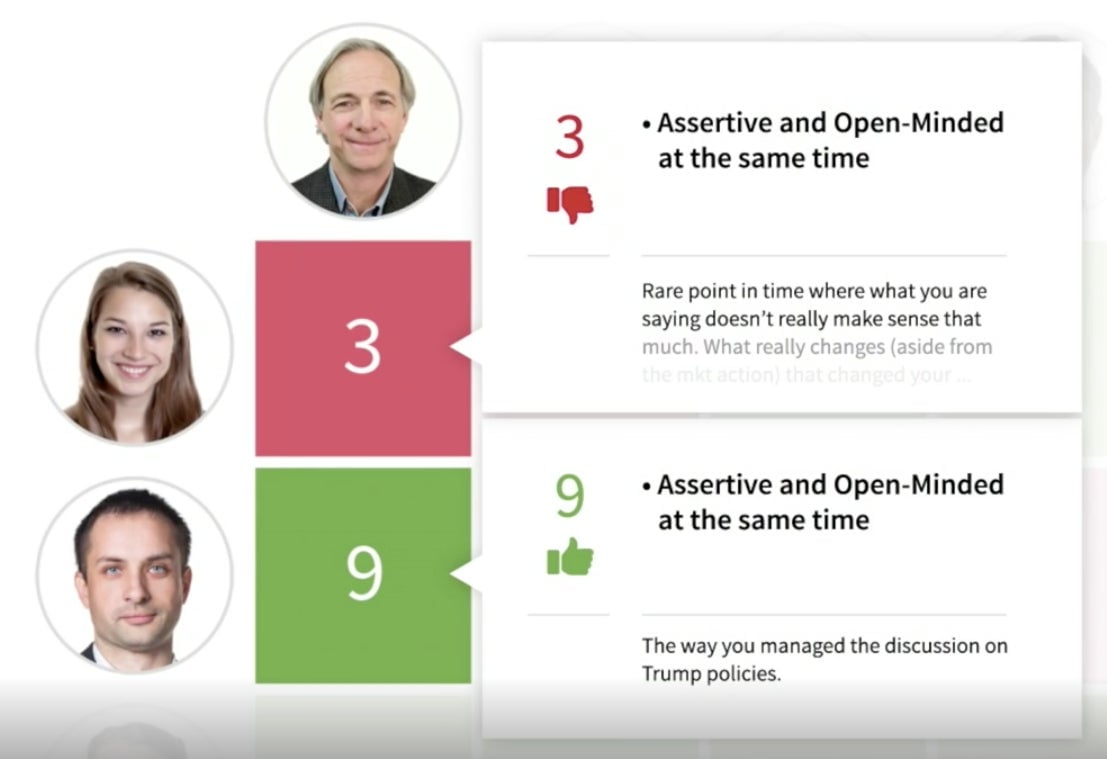

“It has a list of a few dozen attributes, so whenever somebody thinks something about another person’s thinking, it’s easy for them to convey their assessment; they simply note the attribute and provide a rating from one to 10,” Dalio explained in the TED Talk. ”For example, as the meeting [on Trump’s impact on the economy] began, a researcher named Jen rated me a three—in other words, badly—for not showing a good balance of open-mindedness and assertiveness.”

(You can watch Dalio describe the Dot Collector starting at the 9:00 mark in the video below.)

The talk foreshadows Dalio’s highly anticipated, 500-plus-page book, Principles: Life & Work, to be released on Sept. 19.

At Bridgewater, Dalio has built (paywall) what he calls an “ideas meritocracy” by, essentially, banning secrets. In addition to employees giving one another explicit, nearly constant feedback, most meetings are recorded and made available to everyone at the firm. In the spirit of full disclosure, I should note that I worked at Bridgewater for about a year before joining Quartz. But all the information in this article comes from Dalio’s talk or previously published material.

Here’s how Dot Collector works, via screenshots shared in the TED Talk:

1. Employees observe a colleague’s behavior and select the attribute they want to rate them on.

As Dalio notes, some dot attributes include: assertive and open-minded; fighting to get in synch; willing to touch the nerve; holding people accountable; brightness; conceptual thinking; listens well; managerial courage; composed; synthesizing the situation; and taking the bull by the horns.

2. A rating from one to 10 is entered into the app, along with a brief description justifying the numerical rating.

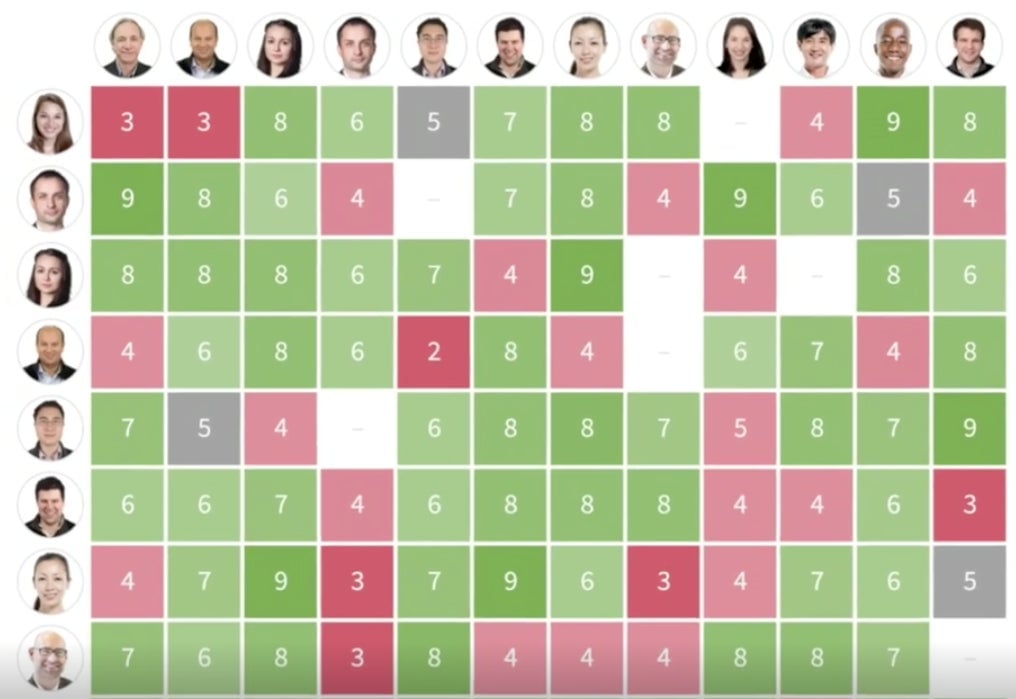

3. As the meeting continues, each colleague is rated on a range of attributes.

4. The feedback is reviewed and digested.

“Different people are always going to have different opinions. And who knows who’s right? Some people thought I did well, others, poorly. With each of these views, we can explore the thinking behind the numbers,” Dalio said in his TED Talk.

“Note that everyone gets to express their thinking, including their critical thinking, regardless of their position in the company. Jen, who’s 24 years old and right out of college, can tell me, the CEO, that I’m approaching things terribly.”

According to Dalio, Dot Collector helps people not only express their opinions, but also to separate out their opinions to view situations from a higher level:

“When Jen and others shift their attentions from inputting their own opinions to looking down on the whole screen, their perspective changes. They see their own opinions as just one of many and naturally start asking themselves, ‘How do I know my opinion is right?’ That shift in perspective is like going from seeing in one dimension to seeing in multiple dimensions. And it shifts the conversation from arguing over our opinions to figuring out objective criteria for determining which opinions are best.”

Behind the Dot Collector is a computer guided by proprietary algorithms that draws all the data from every meeting to create “a pointillist painting of what people are like and how they think,” says Dalio. This pointillist painting of each employee is then used to match them with the right jobs.

“For example, a creative thinker who is unreliable might be matched up with someone who’s reliable but not creative,” he said. “Knowing what people are like also allows us to decide what responsibilities to give them and to weigh our decisions based on people’s merits. We call it their believability.”

In Bridgewater’s internal votes and conversations, explains Dalio, the opinions of more “believable” people (those who’ve repeatedly proven their grasp of a given topic or management trait) hold greater weight than the opinions of less believable people. “This process allows us to make decisions not based on democracy, not based on autocracy, but based on algorithms that take people’s believability into consideration,” Dalio said.

Watching the video of Dalio’s talk, you can sense the audience’s discomfort with the idea of career paths and important firm decisions resting on the emerging patterns of little dots entered into an app. “Yup, we really do this,” Dalio said, amidst the crowd’s nervous laughter. He explained:

“We do it because it eliminates what I believe to be one of the greatest tragedies of mankind, and that is people arrogantly, naïvely holding opinions in their minds that are wrong, and acting on them, and not putting them out there to stress test them. … And we do it because it elevates ourselves above our own opinions so that we start to see things through everybody’s eyes, and we see things collectively. Collective decision-making is so much better than individual decision-making if it’s done well. It’s been the secret sauce behind our success. It’s why we’ve made more money for our clients than any other hedge fund in existence and made money 23 out of the last 26 years.”

Every company won’t jump to build their own Dot Collector—nor should they. But at the least, Bridgewater’s track record makes a strong case for adopting more frequent, clear, and unemotional critical feedback and constructive praise.