The secret to e-commerce in countries with few credit cards: cash on delivery

A version of this post originally appeared on the African Makers collection on Medium.

A version of this post originally appeared on the African Makers collection on Medium.

DO NOT SHIP TO NIGERIA. This warning and others like it fill the advice threads posted by users on Ebay. It’s advice that most sellers on Ebay have opted to follow, and the pattern has driven African consumers to a variety of workarounds, leading people like Ethan Zuckerman to lend a hand as international couriers:

I routinely bring goods to Ghana and Nigeria that friends in those countries have ordered and sent to my office, because they can’t get them delivered to their homes. It’s very strange when people you’ve met only over Twitter send you iPads so you can bring them to Nigeria…

Drawing on the work of sociologist Jenna Burrell in a post called Who let all those Ghanaians on the Internet, Zuckerman catalogues the various forms of exclusion of African users by online companies around the world, from the “failure to include” users who have no access to credit cards, to the “purposeful exclusion” of entire ranges of IP addresses from African countries, which are blocked from accessing their sites. Burrell’s examples from her fieldwork in Ghana include Amazon, Ebay, and Paypal, and several of the major players in online dating.

This raises the question of “clones,” a term often used to describe the African businesses that have sprung up to fill the gap where e-commerce has failed to include African users. In this view, Kivuko is a Tanzanian Amazon clone, and Dealdey a Nigerian clone of Groupon. But to me, the term “clone” seems unfair—would you call a South African maize farm a clone of farms in Iowa, simply because they were bringing mechanized farming to a new market? Is an accounting office in Lagos a clone of firms in New York because it draws on software and bookkeeping practices developed elsewhere?

Bringing an established business model to a new market is one of the most basic forms of entrepreneurship. Though “cloning” internet companies doesn’t necessarily involve the same heavy lifting as building new stores, it does involve building a business around the needs and desires of an entirely different group of consumers, from marketing and product selection,to distribution and methods of payment.

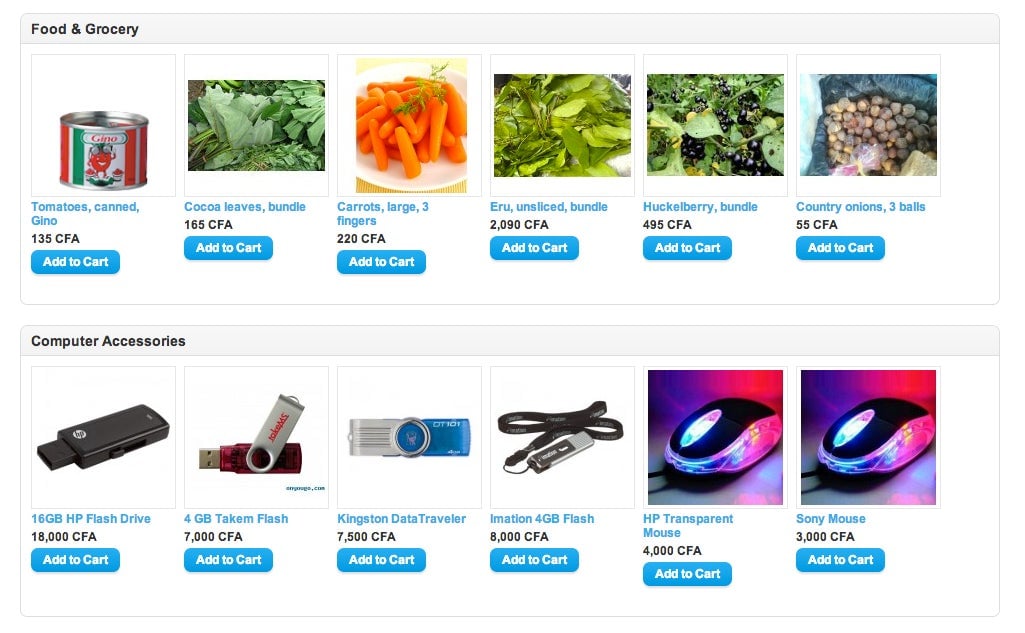

The photo above is a screenshot from the Cameroonian e-commerce platform Makonjoh, which you might describe as a hybrid between Amazon and Freshdirect. As you can see, Makonjoh’s home page offers USB keys and computer mice, right below fresh huckleberries, bundles of cocoa leaves, and country onions. In the US, this combination would be viewed as a complete jumble, but it’s perfectly tailored to the Cameroonian middle class, offering the luxury of home delivery for produce from the open-air market alongside name brand electronics, which can be hard to find in a sea of knockoffs.

The German company Rocket Internet, which owns Nigerian analogs of Amazon and Ebay, is another leading example—doing business in Nigeria means that Rocket’s companies can’t really be clones at all. As Zuckerman points out,

Ecommerce is a credit-card based world. Many African economies, including Ghana’s, are largely cash based. Even for Ghanaians who have the money to buy online services, there’s often no easy way to make an online payment.

So virtually every African e-commerce company has adopted an innovation that would be anathema to e-commerce in the US: paying cash on delivery. This is a re-invention of a central piece of e-commerce, and it’s a practice that American and European consumers would probably be delighted to see cloned back home.

Consider the American practice of showrooming, or testing products in person at brick-and-mortar shops before ultimately buying them online. One of the basic risks of e-commerce, from a buyer’s perspective, is that you can’t really know what you’re getting until you see it, touch it, hold it. Payment on delivery takes the Zappos model of unlimited returns one step further: you don’t need to pay for something until you’ve actually had a chance to look it over.

Online payment is complicated by the question of trust between buyers and sellers, in Africa probably far more than the US, due to the prevalence of counterfeit goods from clothes and shoes to batteries and medicine. Trailing the obvious issue of internet access, trust is often cited as a leading barrier to the spread of internet shopping in Nigeria. As a result, e-commerce in Nigeria has been pulled steadily in the direction of the cash economy. Jumia, an industry leader, has 6 “pickup stations“ in urban areas around the country.

Even in a place like Kenya, where more than two thirds of adults use mobile money and could conceivably pay online, Jumia and others offer a cash-on-delivery option. For Jumia, of course, there are drawbacks to shipping an item before it’s actually been sold, but cash-on-delivery helps build consumer confidence. Kenyans undoubtedly find it reassuring, just as I would in California.

Would American consumers stop show-rooming if they could buy products at one of Jumia’s pickup centers?