The legalization of Islamophobia is underway in the United States

Just a few days after 9/11, then-president George W. Bush delivered a compassionate address to America’s “Muslim brothers and sisters”: “These acts of violence against innocents violate the fundamental tenets of the Islamic faith,” he said, “and it’s important for my fellow Americans to understand that.”

Just a few days after 9/11, then-president George W. Bush delivered a compassionate address to America’s “Muslim brothers and sisters”: “These acts of violence against innocents violate the fundamental tenets of the Islamic faith,” he said, “and it’s important for my fellow Americans to understand that.”

In 16 years, things have changed dramatically. America’s current president has demonized Islam, spreading false rumors about Muslims celebrating in response to 9/11, openly accusing Syrian refugees of being terrorists, and making one of his main policy priorities the curtailing of immigration from certain Muslim-majority countries.

Donald Trump is in many a ways a symptom of a greater shift in American culture: Since 9/11, it has increasingly become acceptable to suspect Muslims of being a threat to the country without the normal proof or justification that would be required if that charge was levied against a member of any other religious or ethnic group. A 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that 50% of US Muslims reported that in recent years their religion was making their lives more difficult, and nearly as many say they faced at least one episode of discrimination in 2016.

And, as researchers at the University of California-Berkeley’s Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society found in a recent report, Islamophobia is also starting to get baked into the American legal system. The report, published Sep. 8, examines dozens of anti-Sharia laws that have been approved in recent years that, the researchers argue, have channeled Islamophobia and, in turn, exacerbated the problem.

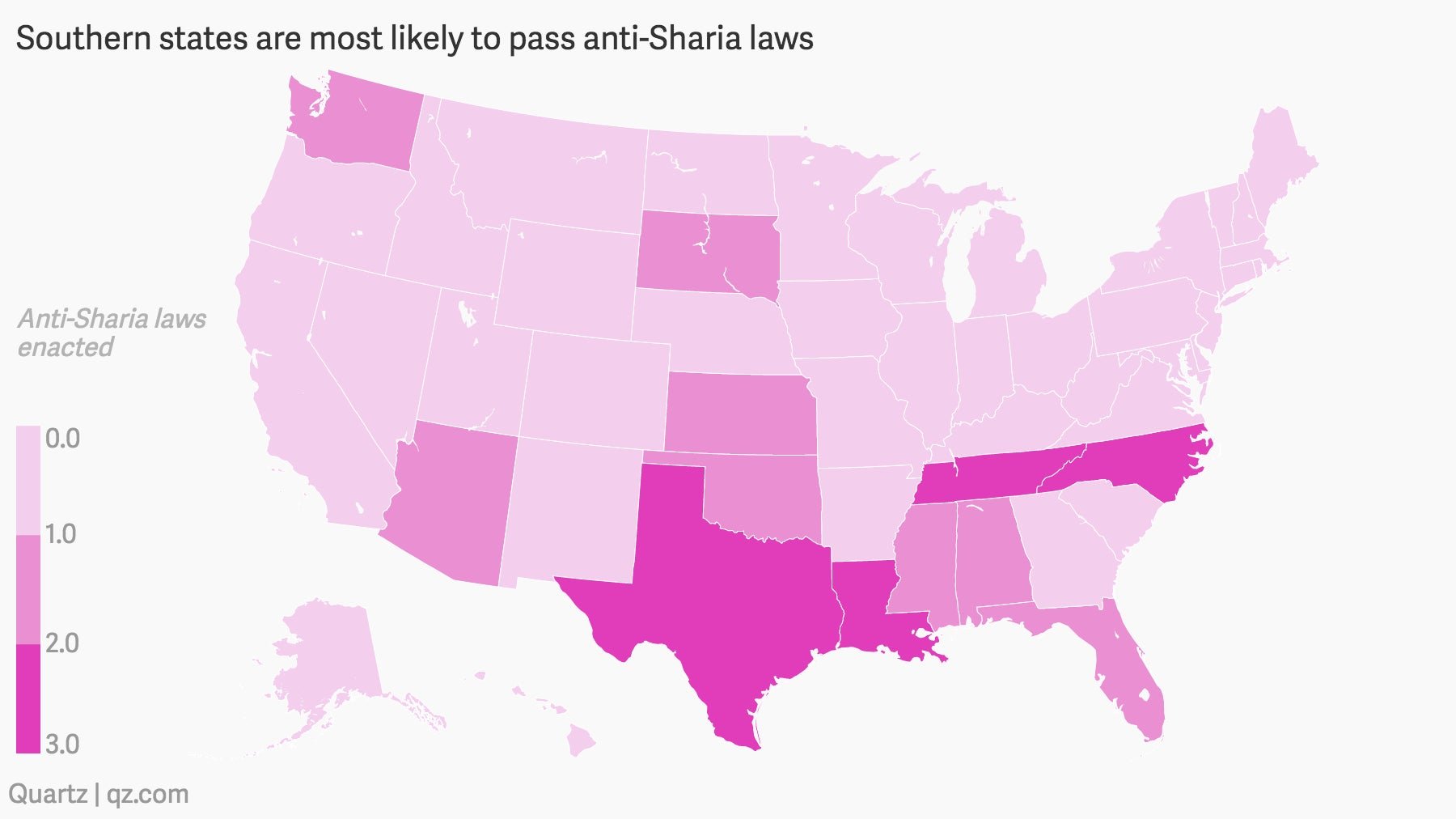

Combing through state legislature websites, the researchers compiled a comprehensive dataset of every anti-Sharia law proposed in US state legislatures from 2010 to 2016, identifying 194 bills in 39 different states. So far, 18 of the 194 bills have been enacted into law in 12 states.

Only 14 of the 194 anti-Sharia laws identified actually included the word “Sharia.” The remaining 180 bills were included because researchers felt confident they could make a strong argument that the intent behind those pieces of legislation was anti-Sharia, often because they were promoted as such by their sponsor.

For example, they included as anti-Sharia any bill that was modeled after the The American Laws for American Courts Act, an act promoted by the anti-Sharia advocacy group The American Public Policy Alliance and written by anti-Sharia activist David Yerushalmi. The text of the Americans Laws for American Courts Act talks about “protecting” the US from “foreign laws” broadly, rather than explicitly from Sharia, yet on the web page that promotes the legislation, the dangers of Sharia are referred to repeatedly, while no other type of “foreign law,” religious or otherwise, is mentioned.

Of the 385 sponsors of anti-Sharia bills identified, 373 were Republicans, and of the twelve states to pass anti-Sharia bills, eight are in the Republican-leaning US South.

The researchers argue that anti-Sharia rhetoric and law-making isn’t, as it claims to be, an attempt to curb extremism, but rather a way to spread an Islamophobic attitude, by identifying Islam with violence and repression. “This represents a demonization of Islam that is a complete distortion of what it is, and is inventing a spectrum of damage that doesn’t actually exist,” says Tisa Wenger, a professor of American religious history at Yale University, who wasn’t involved in this study.

This, the researchers say, is a deliberate strategy to use anti-Muslim rhetoric to polarize the political climate in the hopes of creating a conservative consensus. Building up Islamophobia appears to have become a popular demagogic tactic in US politics: the majority of anti-Sharia laws passed in 2011, 2013, and 2015—each before presidential or midterm elections. “The push for anti-Sharia legislation by lawmakers in a year prior to midterm and presidential election cycles provides a mechanism to normalize, legalize, and proliferate Islamophobia and anti-Muslim sentiment among the American public,” the report reads. As University of Detroit Mercy law professor Khaled Beydoun argued in his paper on political Islamophobia, these bills and laws prepared a fertile ground for Trump’s rise to power.

This isn’t the first time religion has been used as a tool to stir the emotions of the US electorate. From the founding of the US until the late 1950s, Catholics were portrayed as “a danger to American democracy,” says Wenger. Politicians stoked the public’s fear of Catholics by raising suspicion that their loyalty would lie with the pope rather than the US. Catholics, the political rhetoric of the time went, were a threat to American freedom, because they would try to implement religious repression on everyone.

Over time, the anti-Catholic sentiment became conflated with resentment of Italian, Irish, and Polish immigrants and their descendents, most of whom were Catholic and who represented the bulk of the 30 million foreigners who entered the US in 1800s and early 1900s. In the late 1800s, discrimination against the Irish was so common that the label No Irish Need Apply (NINA) showed up regularly in classified ads and the lyrics to popular songs.

Then, as now, Wenger notes, the communities that were most resentful towards Catholics were the ones least exposed to them. “Where the presence [of the minority] is small, that fear and distortion [can] take root,” she says. In recent years, the states that have passed anti-Sharia bills also are among the states with the fewest Muslims. A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that just under 1% of the entire US population was Muslim, and that only three states (New York, New Jersey, and Arkansas) had a Muslim population of greater than 2%. Not one of these states has enacted an anti-Sharia bill. In contrast, eight of the 25 states with a Muslim population of less than 1% enacted such a bill.

This doesn’t surprise Wenger, who says that “familiarity helps to diffuse fear and anxiety.” If you don’t ever interact with Muslims, you are more likely to believe stereotypical, distorted representations.