E-commerce may finally fund tests for all those sketchy vitamins and supplements

Can selling supplements to the masses over the internet change the way we test medical supplements? We’re about to find out.

Can selling supplements to the masses over the internet change the way we test medical supplements? We’re about to find out.

E-commerce drug companies are trying out a new funding model to test vitamins, supplements, and other “enhancing” substances. The industry currently operates in a wild west regulatory environment where contamination, mislabeling, and undisclosed ingredients are common. Governed by the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, the supplements industry operates on what amounts to an honor system.

The US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t test supplements for safety the same way it regulates pharmaceuticals, nor can it act against manufacturers until something harmful happens. That’s lead to pills and products with specious health claims, undisclosed substances, and missing active ingredients. One 2013 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found 274 supplements recalled by the FDA between 2009 and 2012 contained banned drugs (and most continued to do so even six months after their recall). A second study in 2014 showed herbal and body-building supplements caused more liver damage in the US than standard pharmaceuticals.

Even when regulators crack down, they’re outgunned. In 2015, the New York State attorney general’s office charged (paywall) four of biggest US retail stores with selling contaminated herbal products, or products without the listed ingredient at all. Almost four in every five herbal supplements tested in New York lacked the labeled ingredients, and more than 30% were “contaminated with such as rice, pine, beans, and asparagus. Yet little has changed in the $31 billion industry. ”We’re doing the best we can,” Steven Tave, director of the office of dietary supplement programs at the FDA, told Business Insider.

Consumers don’t have any real way to determine what’s in a particular bottle without paying for testing themselves, which is prohibitively expensive. Several standards organizations have sprung up (such as USP) to verify substances, but companies can use the label without independent auditing. ConsumerLab sells reports of different brands through a Consumer Reports-like subscription model for about $42 per year. Or customers can proceed at their own risk reading reviews on sites like Reddit.

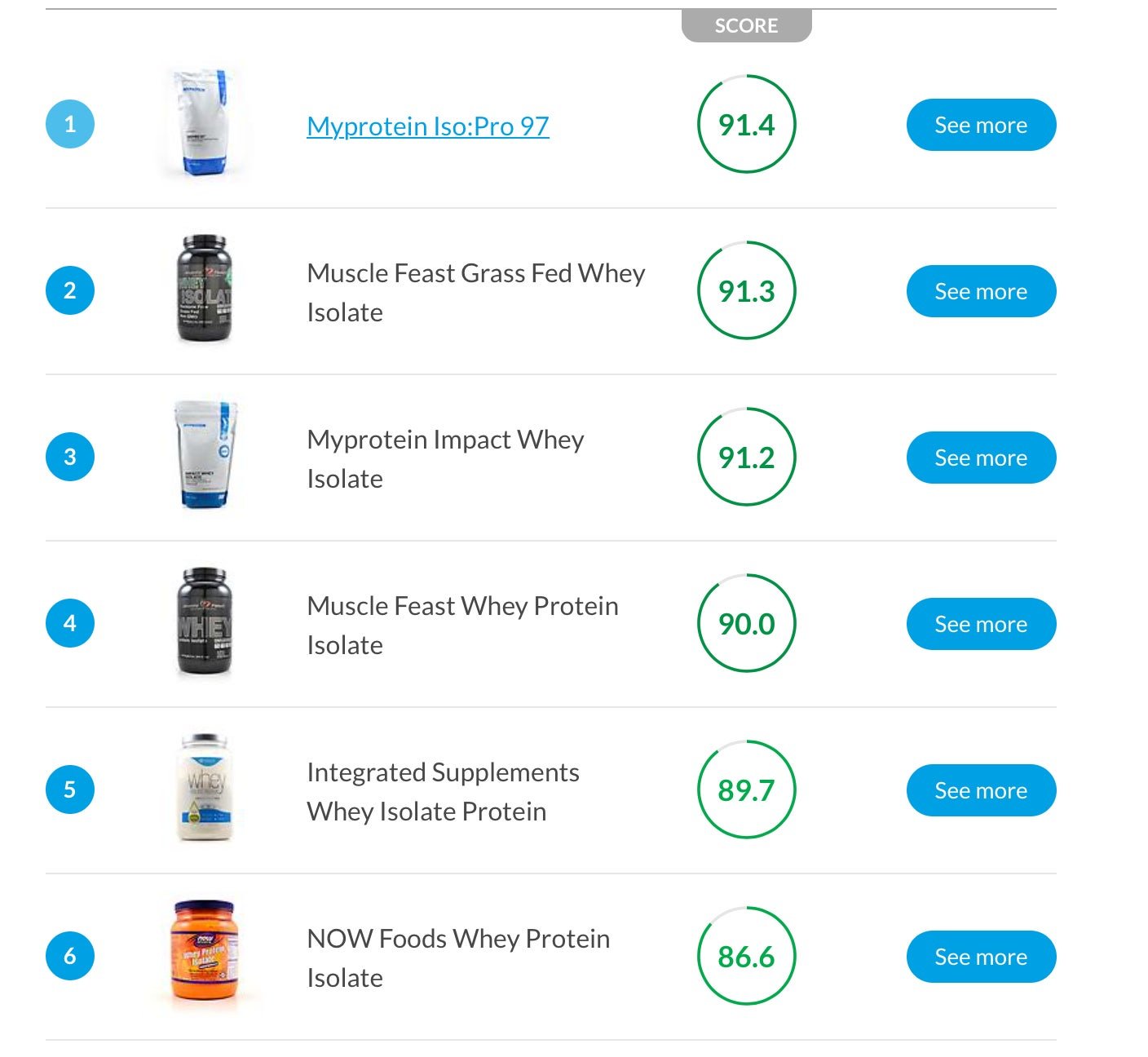

A new model made possible by e-commerce funds independent testing of products through sites that analyze, rank, and sell their products. The concept is simple: Customers shop on online supplement sites, a share of the sales price from referral links is used to fund testing of the products , and they are displayed and ranked according to quality. With e-commerce only now making inroads in the supplements and vitamin industry (close to 90% are still sold offline by companies such as GNC and Herballife, say online retailers), companies can use it to test and verify what the vitamin and supplement industry is selling.

“There isn’t really anything to stop a company from doing anything they want at the product level,” says Neil Thanedar, CEO of Labdoor, who studied chemistry and molecular biology at the University of Michigan before working in the family lab business and starting his online supplements company. “In supplements, products are seen as innocent until proven guilty. You can go to market with any product you want.”

Labdoor is already taking a 20% cut of all the products sold through its site and using it to test products (as well as offering independent testing services). After generating more than $5 million in sales last year, the company had enough revenue to pay for testing of ingredients of about 600 products to ensure what’s on the label is actually in the bottle (and nothing else). Thanedar hopes the company will soon scale up to 100 products per week. “Our testing is unit profitable,” says Thanedar. “If we spend money on testing, we’ll make it back.” The company has raised more than $6 million from Mark Cuban, Y Combinator and other investors.

A second company, Biomarker.io, is selling self-reported customer data directly to health and wellness companies to help them gauge what kind of dietary supplements work. The company provides a white-labeled app that collects data from customers’ wearable devices, fitness & social apps, and genetic/lab services to analyze how well different products work. Customers can access their digital health data in the smartphone app, and Biomarker tells supplement companies whether their products improve customers’ (self-reported) physiological and psychological health, while reportedly showing the impact of dietary and environmental variables.

Yet, even if companies like Labdoor succeed, they’re testing primarily for purity and safety, not efficacy. Whether these substances do what they claim is up to the manufactures themselves under US federal law. Companies must only limit their product claims (paywall) to “supporting” health, rather than preventing or curing specific ailments.

Decades of studies show that the majority of products do not work (or worse). Harvard University estimates supplements cause 50,000 adverse reactions each year, a situation it called “American roulette.” ”Enough is enough: stop wasting money on vitamin and mineral supplements,” a 2013 editorial in the Annals of Internal Medicine implored. The FDA does not have much say in the matter: “a firm does not have to provide FDA with the evidence it relies on to substantiate safety or effectiveness before or after it markets its products,” the agency states.

Amid this dearth of evidence, however, the industry can still count on about half of US adults as customers and millions more in sales every year. At least e-commerce may make it a bit safer.

The cropped image is provided by Carsten Schertzer on Flickr under a CC-BY license.