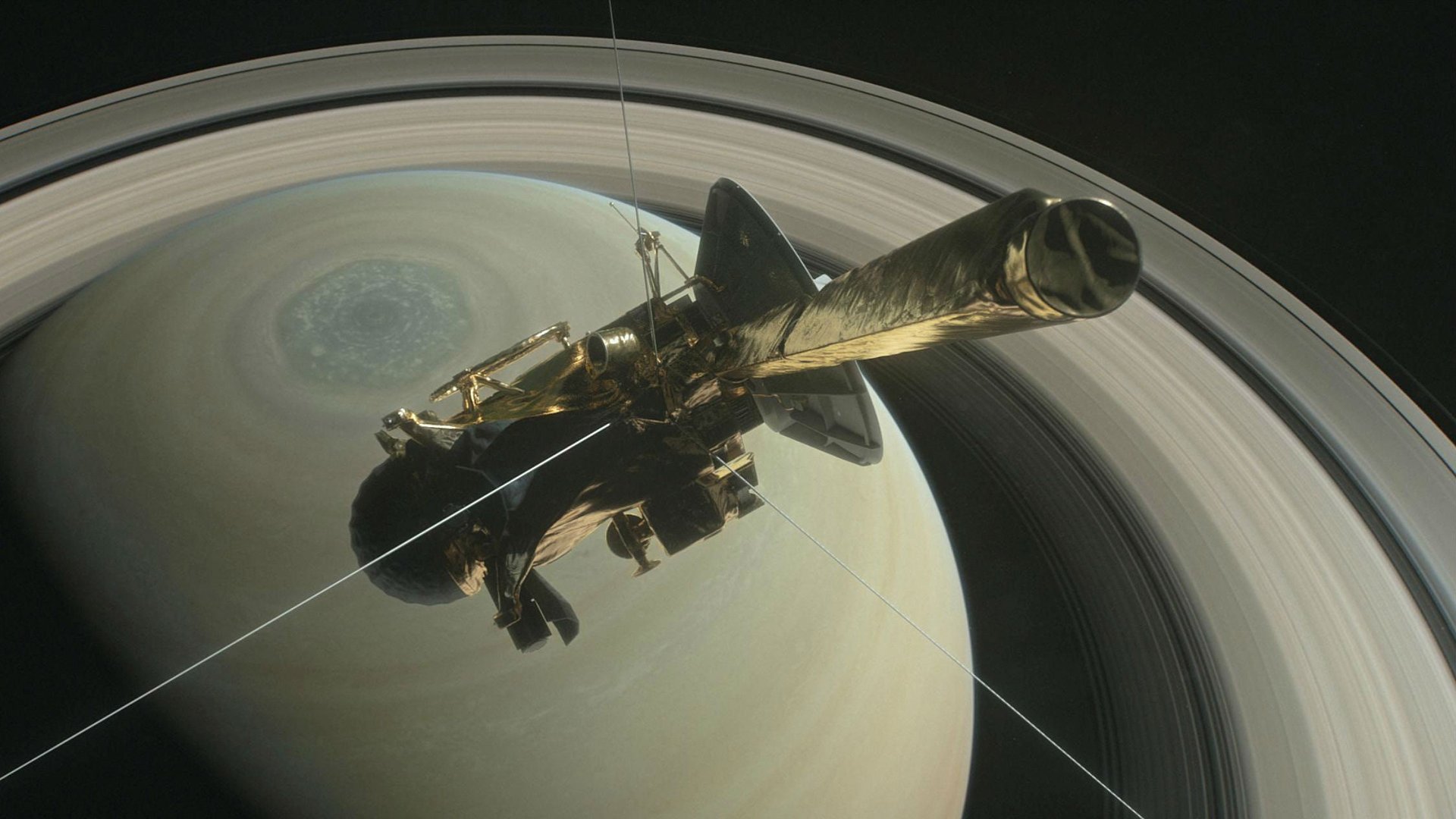

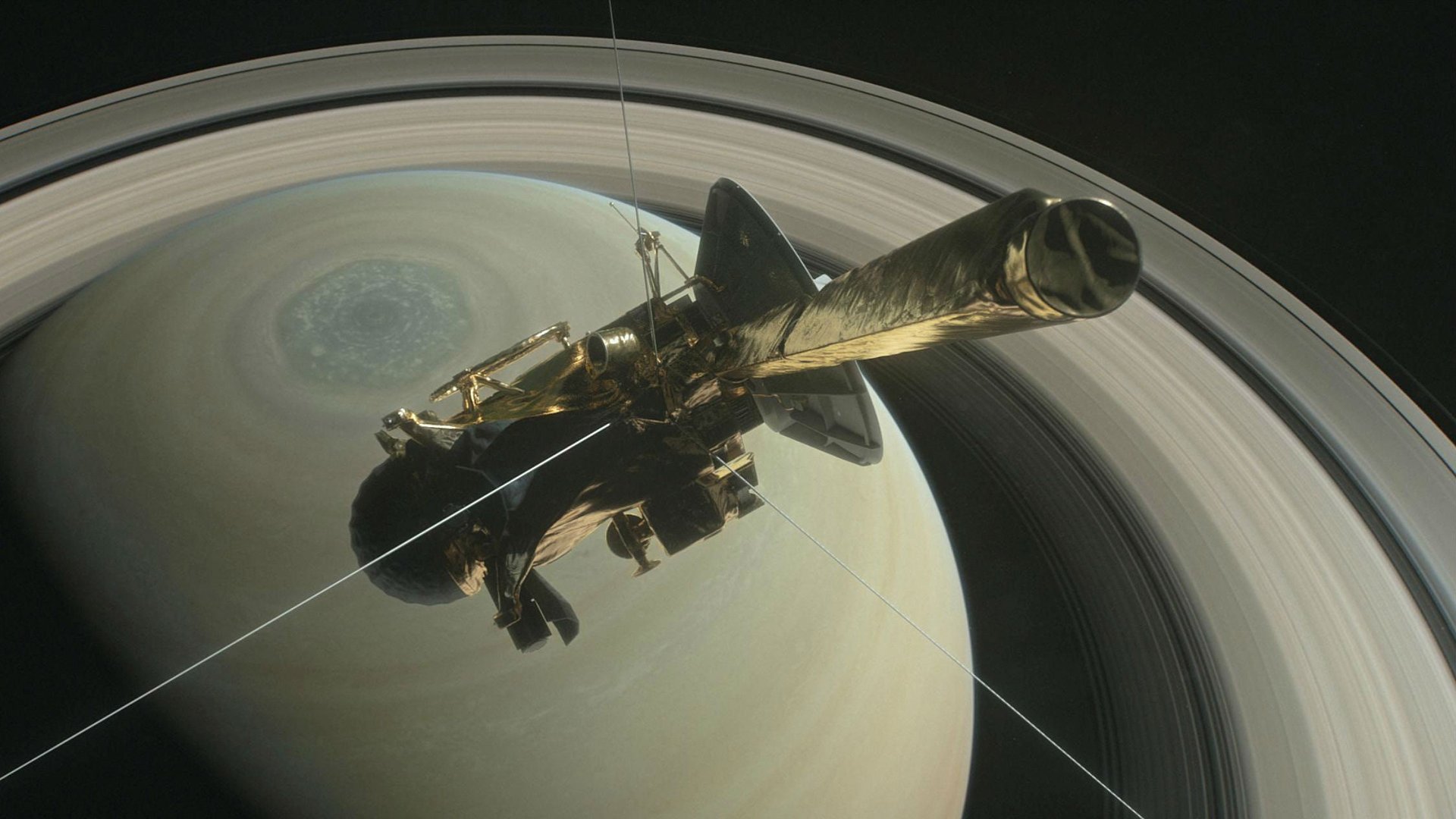

Cassini got to live two lives instead of one

The Cassini spacecraft is poised to commit suicide at NASA’s command.

The Cassini spacecraft is poised to commit suicide at NASA’s command.

For the last 13 years, the brain-child of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency has been diligently collecting data on Saturn. During its interstellar tenure, it explored known moons, discovered new ones, and figured out that the planet’s rings are bustling with meteoroid and dust traffic. On Sept. 15, it will conclude its “Grand Finale” mission—22 deep dives into Saturn’s clouds—and then hurl itself into the planet around 7:55am Eastern time.

When the spacecraft was launched almost 20 years ago, its orbiter and probe were equipped with state-of-the-art technology to conduct in-depth research on the mysterious gas giant. It’s mission was supposed to be only four years long (after the seven years it took to reach its destination), and scientists extended it twice to keep recording more data. Now, though, they’re being forced to kill the $4 billion dollar piece of machinery not because its technology is obsolete or because it stopped working—but because its propellant supply ran out.

Cassini was launched, in part, because of the work that the Voyager and Galileo missions had done to whet scientists’ appetites. These projects launched spacecraft into deep-space, in 1977 and 1989 respectively, to explore the farthest planets in our solar systems. They had turned up some information on Saturn’s rings and moons, but just enough to let researchers know that there was a whole lot more to investigate.

Assembling the two-story Cassini spacecraft was a feat global collaboration over 10 years before its launch in October 1997, according to a series of interviews conducted by the LA Times. Now, 20 years later, thousands of people have worked on or with the 635 gigabytes (roughly 135 DVDs-worth) of data Cassini has pinged back to Earth. The Cassini spacecraft was built with 18 pieces of measuring equipment for 27 investigations, including infrared spectrometers to detect the different kinds of lightwaves in space, a magnetometer to detect magnetic fields, mass spectrometers to detect what elements atmospheres and space dust are made of, and, of course, radar.

Today, these instruments are still capable of collecting data. In fact, Cassini’s mass spectrometer will be collecting atmospheric samples of Saturn just before the spacecraft melts and explodes in its final descent.

Theoretically, researchers back here on Earth could allow the spacecraft to continue to collect data while it glides without friction through space. But they’re worried that the giant metal craft may accidentally careen into one of Saturn’s moons, possibly contaminating an otherwise pristine environment, and alas, without any more fuel, Cassini is uncontrollable. So the scientists have used the last bit of fuel to send Cassini into the planet’s atmosphere, where it will dissolve, and thus pose no contamination risk.

Although the end of a research project like Cassini is devastating, astronomers have more deep-space projects up their sleeves. Linda Spilker, a scientist at the Jet Propulsion Lab who helped launch Cassini 20 years ago, told the Washington Post she’s proposed a plan to explore Saturn’s moon Enceladus for signs of life. And already, NASA’s next approved deep space mission called the Europa Clipper will launch sometime in the 2020’s to explore one of the moons around Jupiter.