Our analysis of five decades of sex research shows an evolving spectrum of sexual norms

One way to understand long-term trends in medical and health research is to analyze the language used in massive bodies of literature produced in the different fields. To better understand the shifting focus of sex research since the field was established, we downloaded (with permission) 4,545 articles published in the Journal of Sex Research and the Archives of Sexual Behavior from 1970 to 2017, and tracked just over 1,000 of the most-used words in these studies.

One way to understand long-term trends in medical and health research is to analyze the language used in massive bodies of literature produced in the different fields. To better understand the shifting focus of sex research since the field was established, we downloaded (with permission) 4,545 articles published in the Journal of Sex Research and the Archives of Sexual Behavior from 1970 to 2017, and tracked just over 1,000 of the most-used words in these studies.

You can use the tool below to explore all of these words, and see how their frequency in the literature has changed over time. Beneath it, we’ve pulled out some of the most interesting trends we noticed and investigated possible explanations for why they’ve occurred.

Humans have been having sex since as long as we’ve been on the planet, but it wasn’t until recently that we really started studying it.

Sexology became a serious field just after World War II, starting with the work of Alfred Kinsey, a biologist at Indiana University, and later founder of the school’s Kinsey Institute, which today studies love and sexuality. Kinsey published his first book, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, in 1948, followed by Sexual Behavior in the Human Female in 1953. In the 1960s, the field was further advanced by the work of lab mates (and lovers) William Masters and Victoria Johnson, who published the seminal Human Sexual Response in 1966.

Around the same time, the first journals devoted to sex research were created. The first volumes of the Journal of Sex Research and the Archives of Sexual Behavior were published in 1965 and 1971, respectively. These two journals served as a central home for sexology research, and encouraged researchers to conduct their studies like they would in any other discipline: with testable hypotheses that could be proven or disproven with the scientific method.

Over the years, issue-specific journals have been created to focus on sex research in areas like the LGBTQ community or HIV research. However, the Journal of Sex Research and the Archives of Sexual Behavior remain the two publications whose articles receive the most citations in a year, which is one way of measuring a journal’s credibility. They’re like the Science or Nature of sexology, and they offer a massive repository of terms that have been used to describe the most popular areas of study.

We found that over five decades, the most popular words in sexology evolved to reflect cultural ideas about what’s normal bedroom behavior. Broadly, these changes reflect major social events over time, including the sexual revolution, the AIDS epidemic, and the civil rights and LGBTQ movements. As sexual norms in the public eye evolved, so did the science studying it.

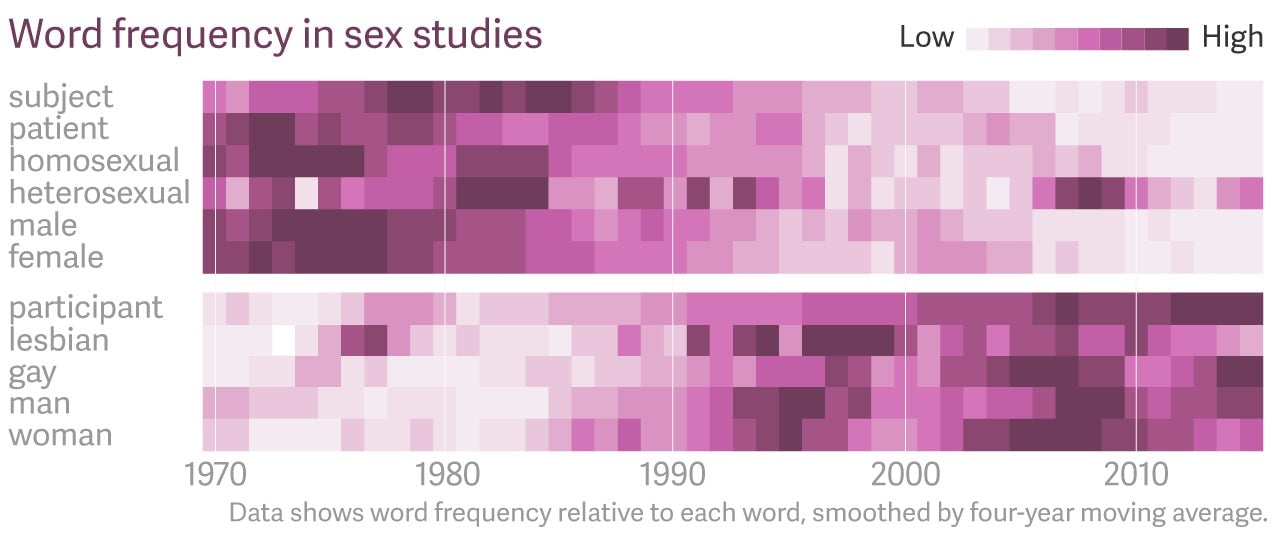

Language has become depathologized

Early on, sex researchers—and scientists in general—tended to talk about people they worked with as objects of study, rather than fellow human beings. The language was stiff and clinical, formalizing sexual behaviors in a way that made them sound like medical conditions. Over time, sexologists adopted more humanizing terms, reflecting a shift toward thinking of volunteers for their work as equals who deserve to benefit from the research. By substituting terms that sound less clinical, researchers indirectly acknowledge that different traits, like sexual orientation, are all normal. Ideally, this attitude would reach health care settings and eventually the greater public.

Subject, patient vs. participant

This shift shows a change in the way scientists think about the people who volunteer for scientific research. “Subject” and ”patient” make the person sound like they have no agency in the experiment. Papers published after the 1990s moved away from these terms to acknowledge that volunteers are also fellow human beings. They were replaced with “participant”—a term that suggests an active, willing role in the research, says Cynthia Graham, a psychologist at the University of Southampton in the UK and current editor of the Journal of Sex Research.

It also reflects the principle that anyone who helps scientists conduct research should be benefitting from it, too. This foundational belief of modern medical research was established in the US in 1979 by the Belmont Report, published by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, to lay out the ground rules for setting up institutional review boards for any scientific research on humans. Moving away from the term ”subject” was not unique to the sex research field; it was also established through the American Psychological Association style guide in 1994. Today, virtually all papers use the terms ”participant” instead of ”subject,” and “patient” is rarely used.

Male, female vs. man, woman vs. individual

The former set of terms implies sex, while the latter set implies gender. Using gender terms instead of sex terms emphasizes the person’s identity as a human being. The term “individual” is especially useful when studies involve those who may not identify with a binary gender, and in cases where sexologist realized that gender identity doesn’t matter for the research.

Men—particularly gay men—have been studied a lot more than women in the field of sex research because of the HIV epidemic. At the start of the crises, in the 1980s, the virus mostly affected men who had sex with men. In the following decade, there’s a striking shift in usage of “man” compared to “woman” in the literature, which reflects the surge of papers related to HIV related to public health.

There are some instances where biological sex is important, which explains why male/female language is still in use (along with the term “intersex” to refer to people who aren’t genotypically and phenotypically male or female). “Biological measures use sex language more than gender language,” says Justin Garcia, a biologist studying sex at the Kinsey Institute. For example, a paper on the physiology of the female organism would use sex language because it’s looking at a particular morphology; papers studying behavior or preferences now use gender language instead.

Homosexual, heterosexual vs. gay, lesbian

“Homosexual” and “heterosexual” are generally considered outdated, overly clinical terms. According to GLAAD, there is a history of using the term “homosexual” to imply that people attracted to the same sex had an undesirable mental health condition. The word “gay,” which normalizes same-sex attraction, became more widely used starting in the 1990s.

In addition to reflecting more accepting attitudes toward people who aren’t straight, the rise in frequency of the word “gay” in the literature also reflects an uptick in papers published about HIV and AIDS, which was at first thought to be a disease that only affected gay men.

However, scientists soon realized anyone can contract HIV. Anal sex, which was then associated mostly with gay men despite the fact that anyone can do it, spreads the virus more often than other kinds of sex because people exchange more bodily fluids that could contain the virus. When researchers recognized that it wasn’t just gay men who could contract HIV, they started using the term “MSM,” which stands for “men who have sex with men.” This term—which becomes more common in the literature in the 2000s and 2010s—makes room for men who are bisexual, or men who identify as straight, but still have same-sex encounters that may include anal sex.

Now, scientists almost always use “gay” or “lesbian” to describe people who aren’t straight. Anecdotally, Graham says that the terms “bisexual” and “asexual” are popping up more in papers she’s read in the past few years, as is the term “heteroflexible,” used to describe people who engage in the occasional same-sex encounter, but are mostly straight.

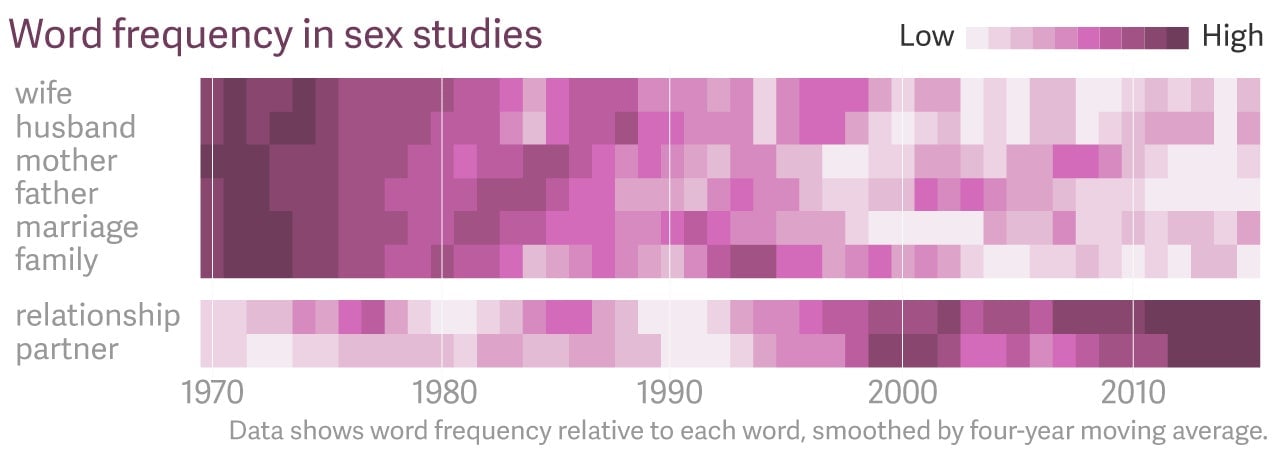

Language reveals a move away from socially defined roles in sexual partnerships

Americans don’t live and interact with each other the way they used to. Marriage rates in the US have declined since the 1970s, and families are a lot more diverse today than the post-war picture of a wife and husband raising kids. There was a dramatic shift in public perceptions of sex beginning in the late 1960s, with growing acceptance of sex outside heteronormative marriages, and in the 1970s, feminists pushed the public conversation to start addressing rape and sexual assault. Sex research evolved alongside these social changes.

Husbands, wives vs. partner,relationship

Sex research increasingly has tried to understand individual behavior, which marital status doesn’t necessarily reflect. Being married doesn’t mean that couples are in a long-term sexual relationship, or that they are only having sex with each other.

Additionally, people have all sorts of relationships with their significant others that fall outside the boxes of “husband” and “wife.” In the past few decades, those terms, as well as the word “marriage” are seen with decreasing frequency in the literature, while the more inclusive terms “partner” and “relationship” rose dramatically.

Traditional familial labels like “father” and “mother” have also become less central in sex research, likely reflecting more fluid contemporary definitions of “family.” In 1960, almost 75% of children were being raised in households with two parents who were on their first marriages; by 1980, that number had declined to 61%, and by 2014 it was 46%, according to surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center. Instead, more children were growing up in households with a single parent, parents who remarried, or as a new category featured in 2014 describes, parents who were living together, but not married.

Consent and Rape

Scientists wrote about rape as early as 1965, but it didn’t become a major area of research until the 1980s—reflected in a huge spike in frequency of the word “rape” in sex research papers in that decade. The change was likely a result of the growing awareness of domestic violence, which followed shortly after the push for equal civil rights in the US in the 1960s.

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill in 1960, which allowed women to take control of their sexuality without the consequence of becoming pregnant. After five years, some 6 million women were taking it. More women having sex meant that more men had sex, too, and intimacy became a topic that could be discussed openly in ways it never had before. This was the onset of the sexual revolution in the US.

This also opened the door to a the first real public conversations about sexual violence. The first rape crisis centers in the US were created in the early 1970s in cities like DC, Berkeley, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston. Title IX, passed in 1972, forced universities to provide resources for anyone who came forward as a sexual assault survivor. The first Take Back the Night march, to raise awareness of sexual assault, occurred in 1978 in San Francisco.

Despite the growing awareness of rape, as an issue, the term associated with its prevention, “consent,” didn’t overtake it until after 2010. Recently, the idea of including consent education alongside regular sex education has gained more popularity; California became the first state to mandate consent as part of sex education in public schools in 2015.

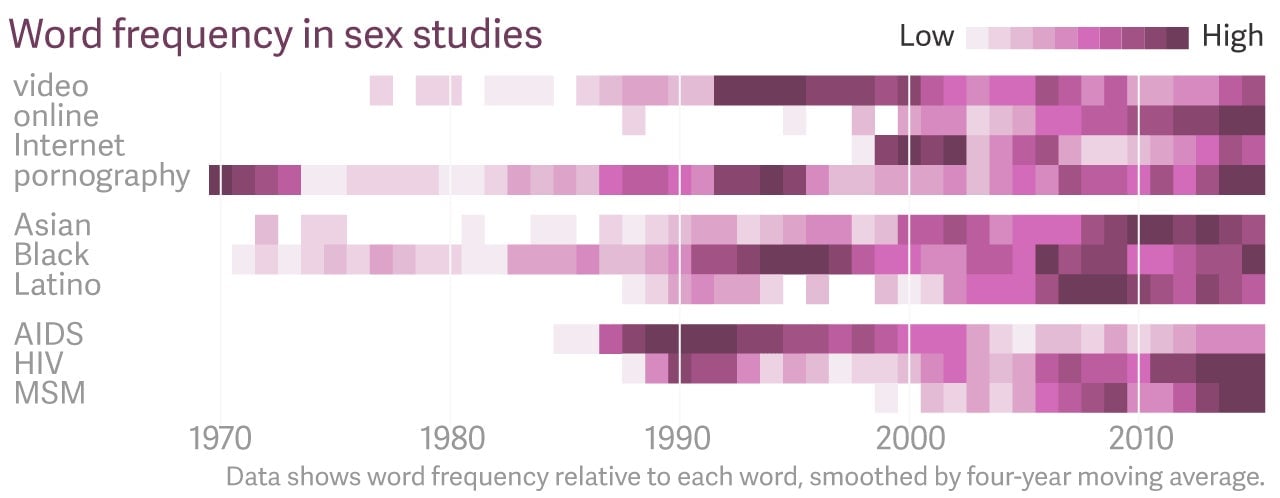

Language reveals broader changes in society

Since the field took off, sex research has broadened to include emerging issues happening in almost real time, including HIV/AIDS, official changes in language used to describe race, and the rise of the internet (and subsequent prevalence of pornography).

HIV vs. AIDS

When HIV research was first conducted in response to the epidemic that started in the 1980s, it often led to a fatal condition that scientists termed AIDS.

“In that time patients were dying…coming for diagnoses really late, and there was only drug treatment which was somewhat effective,” says Graham. Because of the public health concern, and the severity of the illness, there is a huge rise in the number of appearances of the term “AIDS” in the first generation of papers published in the 1990s.

The first drug to treat HIV went to market in 1987; however, it wasn’t until a decade later that more effective antiretrovirals hit the market. With those drugs, it became easier for people living with HIV to manage their condition without developing AIDS. As a result, “HIV” became a more frequently used term in papers published in the 2000s; in the 2010s the use of the term “HIV” shot up even further as researchers began to study permanent prevention regiments, like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and even potential vaccines.

Latino, Asian and Black

The US Census Bureau has had a pretty hard time figuring out how to classify people’s races and ethnicities. “Asian” didn’t appear on census questionnaires until 1960; “Black” appeared from 1850 until 1920, and then didn’t reemerge until 1970, and “Latino” wasn’t a category until the 1980s after Hispanic lobbying groups put pressure on the bureau.

In the sex research papers we looked at, the term “black” first appears in a 1966 paper about interracial relationships (paywall) that primarily uses the racist term “Negro”; “black” is used just twice to describe the anxieties of a white person in a relationship with a woman with skin darker than his. This and other papers of the period were intended for a white audience and uncritically discuss racist ideals. In this same paper, one interviewee expresses concern that being married to “an Asian” would lower his social status—that’s the first instance of the term “Asian” that we found.

The first time “Latino” appeared as keyword in a paper was in 1988, after the term had been approved by the US Census Bureau. The research was addressing (pdf) knowledge disparities among black and Latino communities about HIV. Before that, papers had used the term “Hispanic” on occasion; that word first appeared in a 1977 paper (paywall) about access to reproductive health services, which claimed 15-year-old black and Hispanic teens were as sexually active as 16-year-old white teens.

Scientists weren’t required to include minorities in clinical work until 1993 with the passage of the US National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act. In the field of sex research, some researchers were studying these groups already.

Online, internet and video

From a practical standpoint, the rise of the internet meant scientists could access online databases of information, which partially accounts for the rise in the term “internet” in sex research papers in the 1990s and 2000s.

In addition, though, through those decades, the internet became the place where most of the public accessed pornography. Anyone with a connection to the web could find all kinds of different porn, and were no longer limited to magazines and videotapes or DVDs. One study by researchers at Brigham Young found that between 1973 and 1980, about 45% of men and 7% of women aged 18 to 26 had watched porn in the year they were surveyed; in 2008 to 2012, that number was up to 62% for men and 36% for women.

The rapid growth in the frequency of the term “online” in the literature, particularly in the last decade, reflects a trend in sex research investigating whether more porn available through the internet was creating societal problems. Sex researchers have conducted numerous (mostly inconclusive) studies on whether or not porn influences how men treat women, affects romantic relationships, or is addictive in nature.

The internet also changed how people find each other. The first appearance of the word “internet” is in a paper about swingers from 1998, a few years after the explosion of AOL and when the world was beginning to widely access the internet. Now, it’s fairly common for people to meet online, which could be another reason for the recent uptick in appearances of the word. The internet is home to hundreds of web-based communities for different lifestyles and sexual interests, and apps link up to users’ social media to connect them with others.