North Korea threatened a hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific—which is no stranger to nuclear blasts

North Korea warned Sept. 21 it might detonate a hydrogen bomb over the Pacific Ocean in response to threats made by US president Donald Trump as he addressed the United Nations General Assembly on Sept. 19.

North Korea warned Sept. 21 it might detonate a hydrogen bomb over the Pacific Ocean in response to threats made by US president Donald Trump as he addressed the United Nations General Assembly on Sept. 19.

“This could probably mean the strongest hydrogen bomb test over the Pacific Ocean,” said North Korean foreign minister Ri Yong-ho, speaking in New York late Thursday local time.

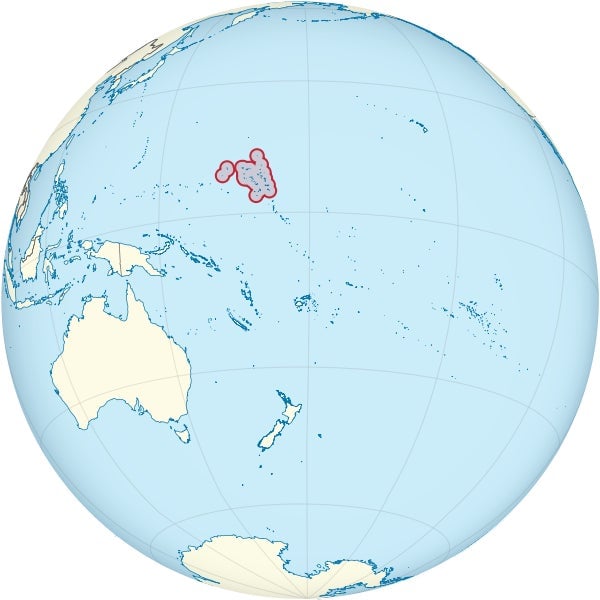

It certainly wouldn’t be the ocean’s first nuclear blast, if it did come to pass. Until 1958, the US conducted nearly 70 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands. The largest, the 1954 Bravo test in the Bikini Atoll, was one for the history books.

A hydrogen bomb, its explosion was a thousand times more powerful than the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, Japan during World War 2. Simon Winchester describes the historic blast in his 2015 book Pacific, in a chapter entitled “The Great Thermonuclear Sea.” He writes:

Bikini’s Castle Bravo bomb was a quite extraordinary event, jaw-dropping, awesome, and, except for a few scientists who had advised caution, generally unexpected. It released a truly vast amount of radiation, and all of it was now spreading fast eastward across the Pacific in an enormous plume of dust and debris that for hours following the explosion was raining chunks of highly radioactive coral down from the sky and contaminating everything below. The explosion was greater than anyone had calculated…

A Japanese fishing vessel was unlucky enough to be 60 miles (97 km) from the Bravo blast. It soon became covered in ash, and the crew began suffering from burns, nausea, hair loss, and other ailments. Back home they were quickly diagnosed with acute radiation sickness by doctors who knew from the war what they were seeing. The ship’s radio operator died from acute organ malfunction about six months later. Other crew members succumbed to cancer and other ailments.

If North Korea did decide—and manage—to detonate its own hydrogen bomb in the Pacific, it would similarly put at risk people on ships or even land, depending on the location, not to mention create long-lasting environmental damage.

“We are talking about putting a live nuclear warhead on a missile that has been tested only a handful of times,” Vipin Narang, a nuclear strategy expert at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told the Guardian. “It is truly terrifying if something goes wrong.”

Or, indeed, if all goes to plan.