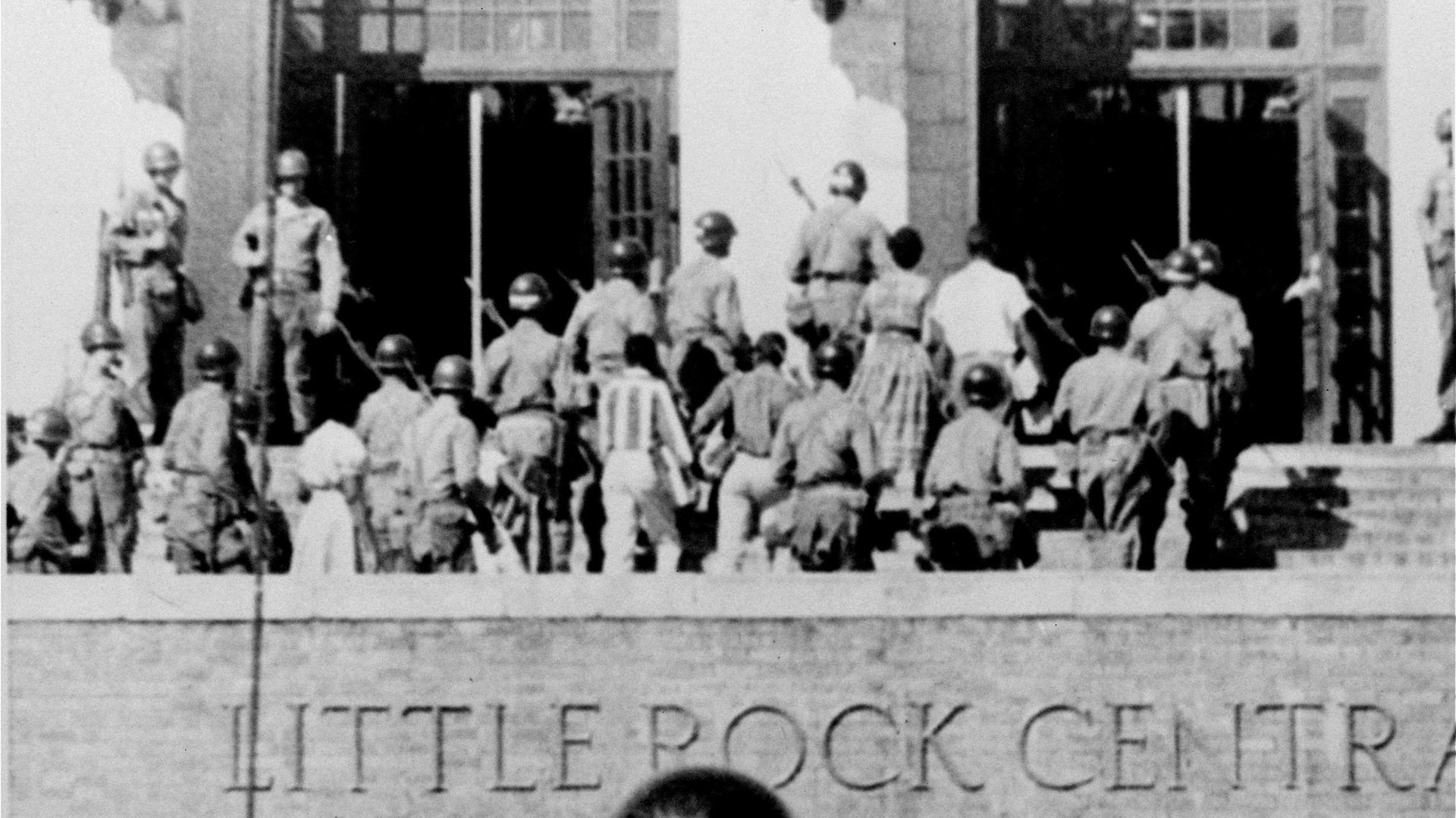

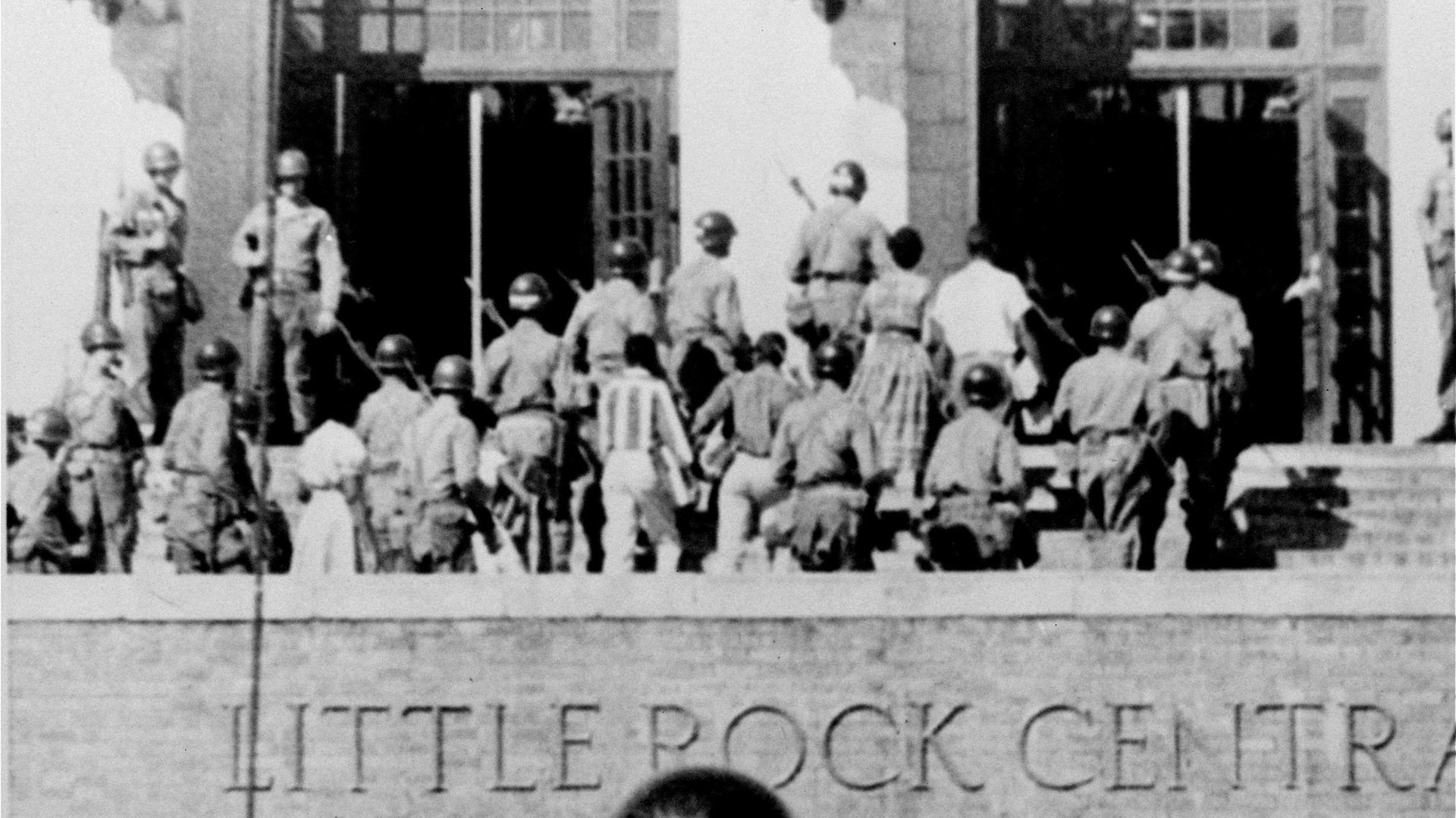

Photos: Sixty years ago, nine black students in Little Rock were escorted into a white school

On Sept. 25, 1957, nine African-American students in Little Rock, Arkansas were escorted by federal troops into Central High School after they were initially barred from entering by the Arkansas National Guard.

On Sept. 25, 1957, nine African-American students in Little Rock, Arkansas were escorted by federal troops into Central High School after they were initially barred from entering by the Arkansas National Guard.

The image of peaceful, brave high-school students making their way through an angry, white, violent mob in order to get the same quality of education as white students became a defining image of the civil-rights era.

The act of protest was “a physical manifestation for all to see of what that massive resistance looked like,” Sherrilyn Ifill, director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, told the AP. “The imagery of these perfectly dressed, lovely, serious young people seeking to enter a high school… to see them met with ugliness and rage and hate and violence was incredibly powerful.”

The Little Rock Nine—Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals—entered the school three years after the landmark 1954 Supreme Court ruling, Brown v. Board of Education, which banned segregation in schools.

Desegregation in Little Rock public schools was in name only—the Little Rock Nine were subjected to a year of verbal, emotional, and physical abuse at the hands of white students and Little Rock public schools shut down altogether the next year to avoid having to integrate even further in what was known as “the lost year.“

Then and now

Reflecting on the bravery of Little Rock Nine and all the abuse they endured brings to light a troubling fact: Little Rock School District’s segregation problems have never really gone away.

In 1971, schools in the area established mandatory busing practices in an attempt to better integrate Little Rock’s schools after a US District Court case brought by Delores Clark, an African-American mother, found that black students were being denied entrance to predominantly white elementary and junior high schools. In response, white families increasingly left the district.

In 1984, Little Rock was approximately 65% white, yet 70% of the students in the district were black. Critics charged that white students were leaving Little Rock to go to the other two districts in Pulaski County, North Little Rock school district and Pulaski County special school district. The courts found that all three districts were unconstitutionally segregated, and they were placed under court supervision until they could be declared unitary (meaning they met the criteria for desegregation put in place by Green v. County School Board of New Kent County in 1968). Little Rock and North Little Rock weren’t ruled unitary until 2014; Pulaski County special school district is still under supervision.

The 2014 settlement ruled that the state of Arkansas would continue to pay $65.8 million a year through 2018 in continued desegregation efforts, such as aid with student transportation, and facilities project to improve the condition of schools in the district.

Last year, the Civil Rights Project at UCLA reported a “striking rise” in segregation by race and poverty for African-American and Latino students in schools that “rarely attain the successful outcomes typical of middle-class schools with largely white and Asian student populations.” The group found that 1988 was a “high point” in terms of the share of black students in majority-white schools, but since then, the percentage of “intensely segregated nonwhite schools” (10% or less white students) rose from 5.7% to 18.6% of all public schools.

On the 40th anniversary of the Little Rock Nine in 1997, president Bill Clinton addressed the nation from the steps of Central High School. “Segregation is no longer the law, but too often separation is still the rule,” warned Clinton, who is from the state. “Today, children of every race walk through the same door, but then they often walk down different halls. Not only in this school, but across America, they sit in different classrooms, they eat at different tables. They even sit in different parts of the bleachers at the football game.”

Today, the Little Rock school district is still two-thirds black and has been under state control since 2015 because some of its schools are in severe “academic distress.” Despite the state paying millions and millions of dollars over the course of decades in an effort to desegregate Little Rock, the district has changed very little from the Jim Crow-era education system the Little Rock Nine sought to disrupt all those years ago.

Perhaps it’s not as blatant as it was in 1957, but signs of segregation are there. “White flight” continued, and increased white attendance at private schools has led to a Little Rock that is almost 50% white, but a school district with a white student population of only 17.8%.