Suddenly people are breathing a very cautious sigh of relief about Europe

A year ago today, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi made a market-moving promise: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough,” he said in a speech in London.

A year ago today, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi made a market-moving promise: “Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough,” he said in a speech in London.

So far, the ECB has done just that. The statements swiftly pushed down borrowing costs for troubled countries like Spain and Italy, preventing them from having to seek an international bailout. Although almost all European economies saw economic contraction in the next few months, the market no longer believed in the euro’s imminent collapse.

On the anniversary of that speech, the euro zone is getting even more good news. A handful of economic indicators published this week suggested that the euro zone may actually return to growth in the second half of 2013.

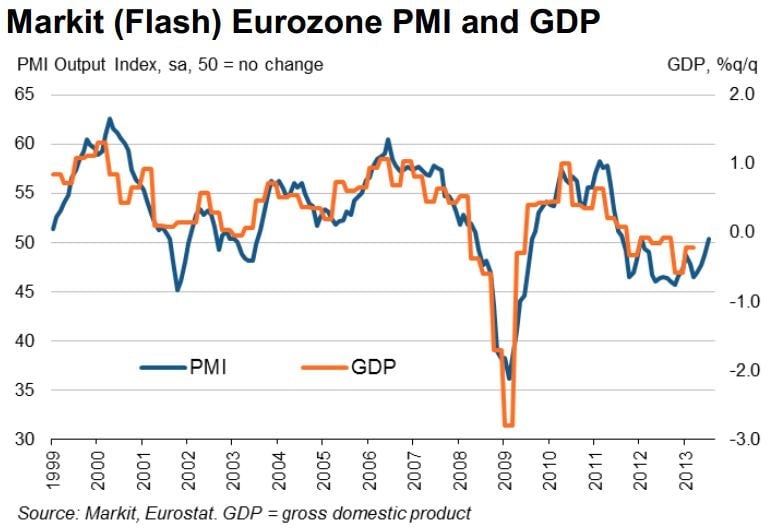

First, Markit’s purchasing managers indices (PMI)—combining managers’ outlook on sales, employment, prices, and new orders—hit multi-year highs for both the services and manufacturing sectors. In this index, readings above 50.0 suggest that output is growing, and readings below 50.0 suggest the economy’s slowing. The overall PMI index for the euro zone rose to 50.4 in July, from 48.7 in June.

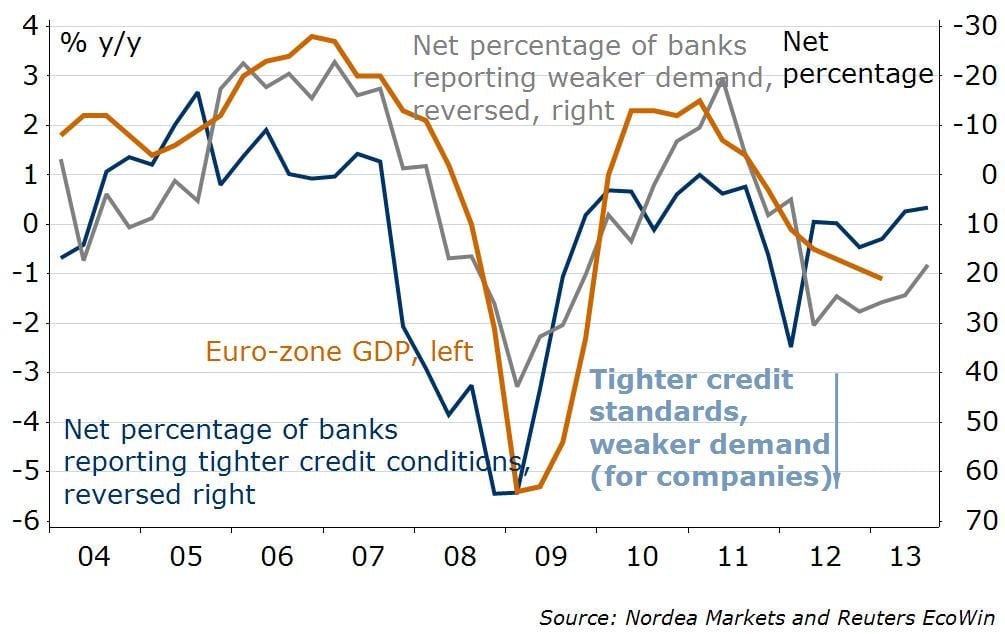

Surveys about banks’ lending habits may be even more compelling. According to a lending survey released by the ECB this week, banks say they aren’t seeing credit tighten further, and have eased lending standards slightly. Banks also say that slightly more consumers want loans.

“All in all then, the picture for households is starting to look better, as far as the credit environment is concerned, while companies, most likely foremost small and medium-sized ones, continue to face a grimmer picture,” writes Jan von Gerich, an analyst for Nordea Markets.

Last week, the ECB announced that it would accept a wider range of asset-backed securities—financial products made from packaging loans to businesses—as collateral against which banks could borrow from the ECB. The central bank hopes this will encourage more banks to issue loans to small businesses.

Despite these positive signs, southern Europe is far from fixed. The economies of Greece, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, and Spain are still contracting. So the euro area still faces the ultimate wild card: a mix of political instability, high unemployment, and anger that could bubble over at any time.