Superbug in Chinese pork raises questions on Smithfield deal—but not the ones US politicians are asking

Shuanghui’s $4.7 billion takeover of Smithfield Foods, the US’s biggest pork producer, has been a popular target for US politicians, on the grounds that it might pose a danger to America’s strategic access to bacon, or even its supply of the blood heparin. But what about the risks that American-style pig production—with its heavy reliance on antibiotics—might pose to China?

Shuanghui’s $4.7 billion takeover of Smithfield Foods, the US’s biggest pork producer, has been a popular target for US politicians, on the grounds that it might pose a danger to America’s strategic access to bacon, or even its supply of the blood heparin. But what about the risks that American-style pig production—with its heavy reliance on antibiotics—might pose to China?

Scientists in Hong Kong have just discovered a strain of drug-resistant bacteria on pork imported from mainland China known as ”vancomycin-resistant enterococci,” or VRE. The superbug has only been found once before in China, in chicken exports bound for Japan, according to a study published July 19 in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

However, VRE is common in the US, where it first appeared in the 1980s. In the United States, where the meat industry uses 80% of the nation’s antibiotic supply on livestock, a government study released earlier this year found antibiotic-resistant bacteria in 69% of pork chops and 55% of ground beef.

That doesn’t mean that China’s meat industry is necessarily much better, when it comes to antibiotics; China already has a “huge burden of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in livestock,” scientists from the University of Hong Kong wrote in the July 19 study. But there is little to suggest that the problem will be improved after Western techniques and expertise are brought into the country, and it could easily become worse with bigger, consolidated US-style farms where the animals are routinely dosed with antibiotics.

So far, the VRE superbug that researchers discovered in Chinese pork does not appear to be widespread—just one out of 137 samples tested positive—but the specific type of VRE has them worried. The particular sequence “is highly adapted to pigs,” said Pak Leung Ho, the lead author on the report and an associate professor at Hong Kong University’s Department of Microbiology, in an interview. “I really worry it will become endemic quickly,” he said.

“There is a danger of antibiotic resistance in food animals, but people are not taking it seriously in China or the United States,” he said. Experts ranging from the US Department of Agriculture to the World Health Organization have tried to address the problem and made useful recommendations, Dr. Ho said, but none of the global industry leaders are following them, he said. The study he co-wrote recommended “stricter regulation and monitoring of antibiotic use in animal husbandry.”

VREs generally only cause disease in already-sick individuals, so this discovery is unlikely to signal the beginning of widespread health problems. But their newly discovered presence in China could signal a worrying trend in a country already wracked with food safety scandals and rising public anger about food quality.

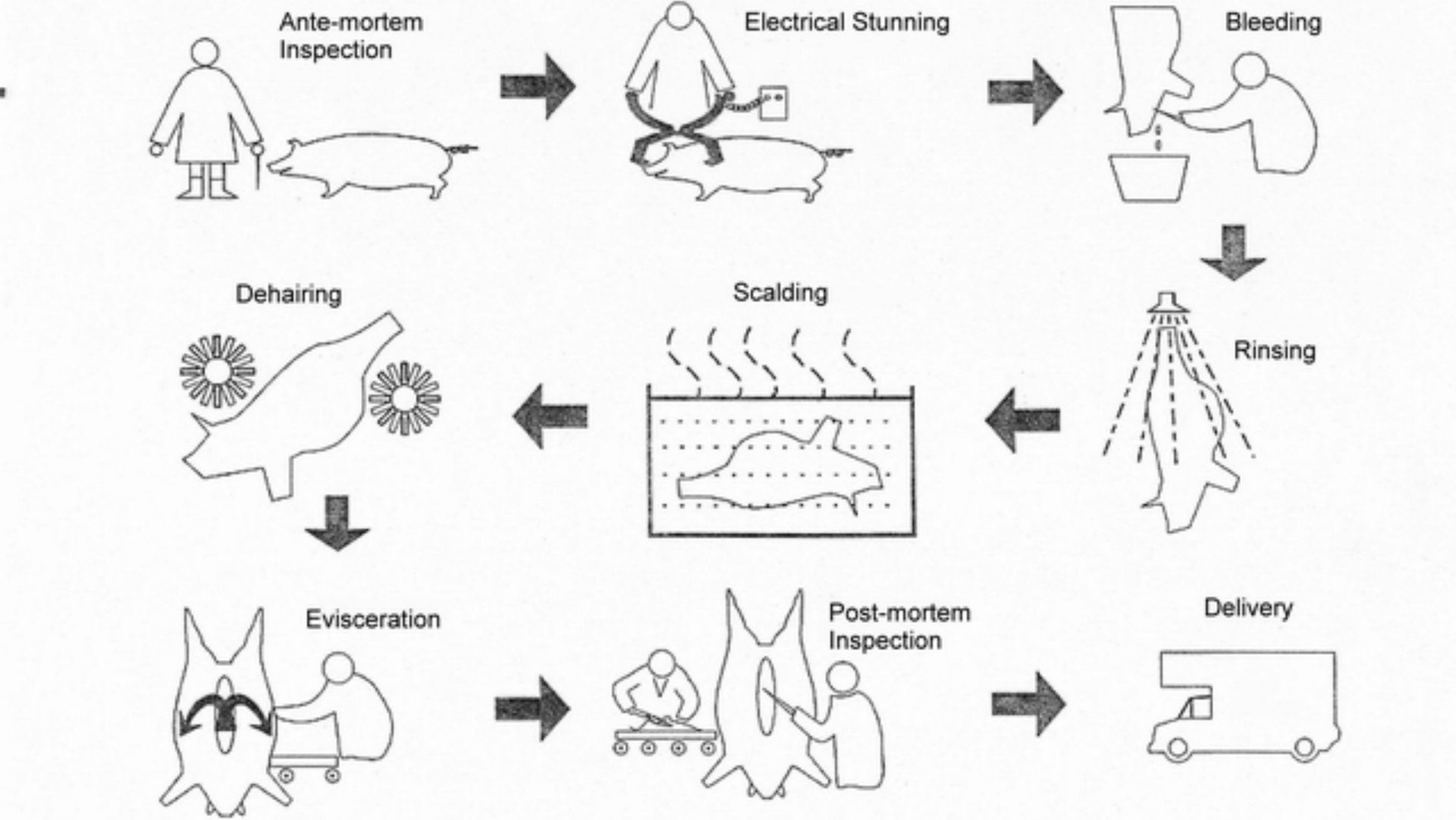

Hong Kong’s fresh pork, mutton and beef come from three slaughterhouses within the special administrative region, including Sheung Shui, where tests for this study were conducted. Tracking the pork’s origins to a particular farm is impossible, the scientists said, because it comes from multiple sources in mainland China, but Hong Kong’s government says this production is closely monitored, as this chart illustrates.