Amazon’s Whole Foods deal isn’t disrupting grocery prices

When Amazon’s acquired Whole Foods for $13.7 billion, it announced it would start slashing prices on some of the grocery chain’s best-selling items. Customers took note and flocked to stores for cheap baby kale and “responsibly-farmed” salmon. The first two days after prices dropped, the number of Whole Foods shoppers swelled by 25%.

When Amazon’s acquired Whole Foods for $13.7 billion, it announced it would start slashing prices on some of the grocery chain’s best-selling items. Customers took note and flocked to stores for cheap baby kale and “responsibly-farmed” salmon. The first two days after prices dropped, the number of Whole Foods shoppers swelled by 25%.

So is the retail giant on track to disrupt the marketplace for organic produce in the US? To answer this question, Quartz looked at the advertised retail prices of fruits and vegetables across the continental US, using data from US Department of Agriculture for a wide array of products.

Let’s start by looking at avocados—the second item Amazon said would become more affordable, right after organic bananas.

In the week following the acquisition, the average advertised organic avocado price went up, not down. Nationally, the fruits are now more expensive than a year prior.

Since the takeover, the average price of organic avocados has bounced around, but remained within typical levels. Conventionally grown avocados have remained at mostly constant prices.

The gray chart above shows the premium paid for an organic avocado, as calculated by subtracting the average advertised price of the organic fruit from a conventionally-grown one. You can see that premiums for avocados differed drastically this year compared to last.

It’s not just avocados. This trend holds true for other US produce staples.

Amazon took over Whole Foods roughly two months ago and the advertised prices of organic produce—a mainstay of Whole Foods’ offering—are essentially back to where they were at the time of the takeover after a seasonal dip.1

Conventionally grown varieties have been advertised at higher prices, meaning the difference in price between organic products and their non-organic counterparts has shrunk. These changes, however, are similar to the same period a year ago.

If Amazon was driving down prices, you would expect to see conventional produce prices remain the same, organic produce getting cheaper, and the difference between the two narrowing. This has not happened.

The market for supermarkets

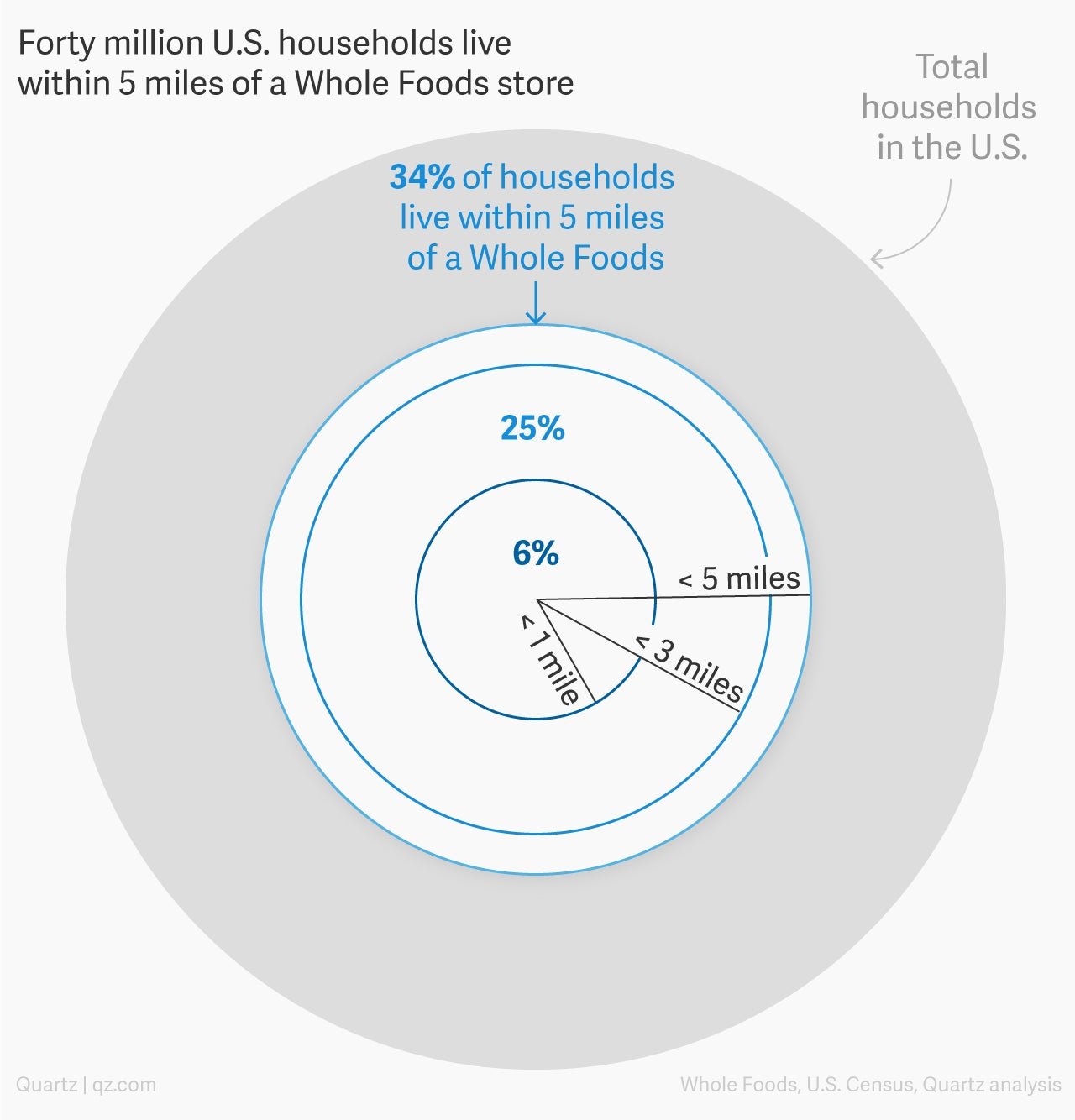

With about 450 US stores primarily in metropolitan areas in proximity to 75 million of America’s richest shoppers, Whole Foods is a large player in grocery, but by no means a dominant one. Companies like Kroeger, Wal-Mart, Aldi, and Albertsons have a thousand or more locations. Nonetheless, those other markets will have to react to Whole Food’s discounting to remain competitive.

Even in neighborhoods that don’t have Whole Foods, its pricing could have an outsized influence on its cross-town competitors. So far, there’s not much to react to. A study of a Princeton, New Jersey Whole Foods location showed that prices store-wide are only down 1.2% since the takeover (paywall).

If supermarkets are changing their prices–and there are dozens of reasons why they change them–our analysis suggest that Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods isn’t one of them.

A line-up of organic food prices

Here’s a look at some of the most widely stocked and advertised organic produce products and how their prices have changed since the takeover.

Another featured Amazon sale item, organic bananas, are consistently priced throughout the year. Ahead of the deal, the premium for the organic variety was consistently higher on a year over year basis. Since Amazon took over, the premium on organic has been both lower and higher looking year-over-year.

Bags of organic baby carrots got slightly cheaper into September and October. Looking back a year, however, the same thing happened. The premium for organic, however, is higher than a year prior.

One of the most popular items for stores to advertise, the promotional prices of red seedless grapes, have hardly changed in months.

Organic mango prices jumped in the final week of September after remaining steady for weeks. Conventionally grown mangoes haven’t moved as much. It’s a similar trend to a year prior. In late September organic mangoes got expensive, while conventional mangoes did not. The premiums paid for an organic mango are lower than a year prior.

The end of summer also brought an end to cheap organic blueberries. By the middle of September last year, no stores surveyed by the USDA were advertising their blueberry prices. This year, there were still ads for both conventional and organic varieties into October, with organic prices hitting a 52-week high, creating the largest price premium of the year.

The prices of organic yellow onions have stayed consistent with price levels from a year ago. The premium for organic has been about the same as well, though the most recent figures show a year-over-year divergence.

Organic cauliflowers are being advertised at higher prices this year while prices of the conventionally grown varieties have stayed consistent. As such the premium for organic was much higher than the year prior until organic prices dropped in the first week of October.

Behind the deals

The data analyzed here is derived from a weekly survey of thousands of supermarket locations’ advertising circulars. The prices are not representative of all in-store prices, just those prices which supermarket companies are actively promoting to their customers.

Of course, the motivations for advertising a product can be myriad. Produce needs to be sold before it spoils and organic products are typically less hearty. Advertising deals can bring shoppers into the store to clear the shelves.

But advertising can also promote a false perception of a deal to an uneducated consumer, increasing margins. When Amazon first announced it was discounting prices at Whole Foods, the company described the celebratory sales as a ‘down payment’ on the company’s vision to make natural and organic food affordable. Given how little prices have changed, it looks like the behemoth still has a ways to go before they’ve made good on their promise.