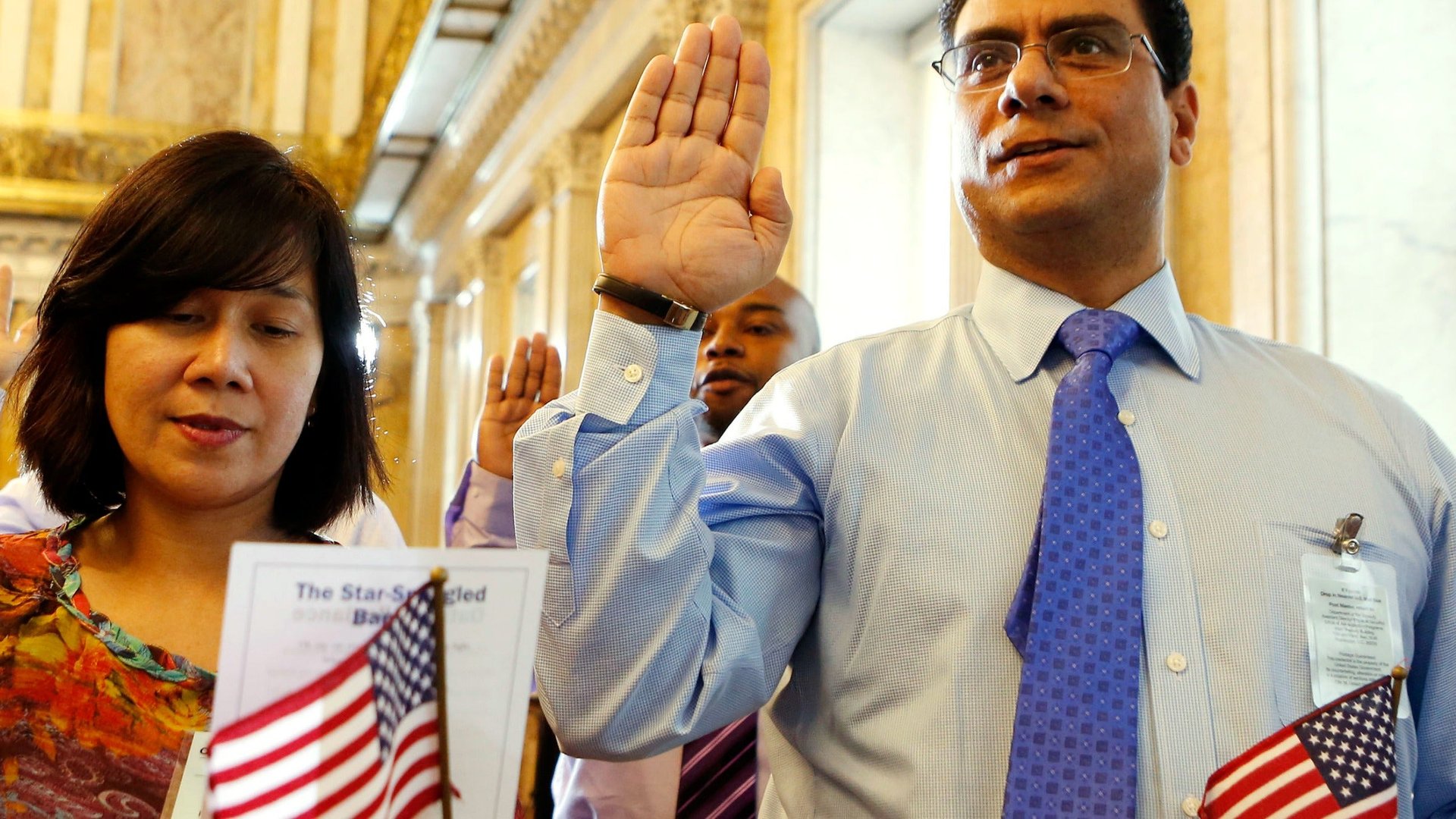

Almost all of the growth to the US labor force by 2050 will come from immigrants

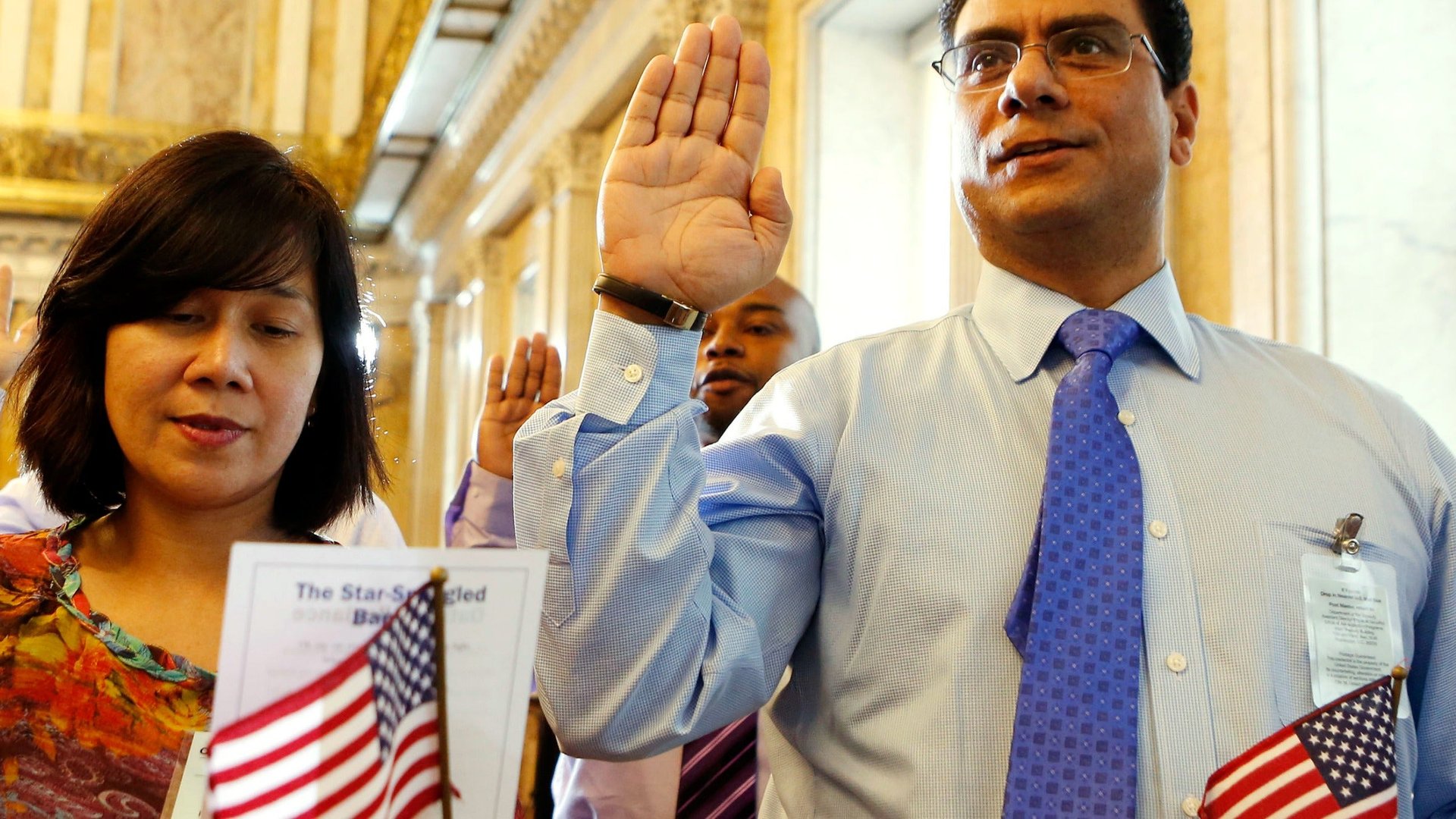

Recent polling shows that 72% of voters in the US consider immigration a net positive for the country but it’s not clear whether Congress has gotten the message. While the Senate passed a strong immigration reform bill last month, the House of Representatives seems less eager to act, and probably won’t produce a bill for weeks if not months.

Recent polling shows that 72% of voters in the US consider immigration a net positive for the country but it’s not clear whether Congress has gotten the message. While the Senate passed a strong immigration reform bill last month, the House of Representatives seems less eager to act, and probably won’t produce a bill for weeks if not months.

While the federal government dithers and fumbles, metropolitan areas have to step up on immigration. Metros—collections of economically related cities and suburbs led by networks of elected, civic, corporate, and philanthropic leaders—are on the front lines of immigration. Some 85% of the nation’s foreign-born are living in just the 100 largest metropolitan areas.

Here are three things that metropolitan leaders should do while immigration reform is stalled in Washington.

First, understand how immigrants fit into your geography and economy. Immigrants and their children will likely account for almost all of the growth in the US labor force through 2050. As taxpayers, immigrants contribute to the local economy and bring federal dollars from things like the earned income tax credit and childcare tax credit into circulation in local stores, doctor’s offices, and businesses.

Moreover immigrants also create jobs. As Mayor Rahm Emmanuel stated recently, in Chicago, 50% of all small business applications come from immigrants. And in a world where global connections are increasingly critical to economic growth, immigrants can provide a metropolitan area with a built-in global network, contributing personal, professional and economic links to their home countries. Indeed, the Small Business Administration has found that immigrant-owned businesses are more likely to export (pdf) goods and services abroad than native-owned firms.

Many people’s view of where immigrants settle and what work they do in a metropolitan area is decades out of date. In 63 of the 95 largest metros, including Atlanta, Detroit, and Orlando, the majority of the foreign-born population lives in the suburbs, rather than the central city. Immigrants are also coming to the United States with a range of skills. The Seattle, San Francisco and Washington, DC regions attract high-skilled immigrants, while Houston, San Antonio and Wichita tend to draw a greater share of immigrants lacking a high school diploma.

Second, metropolitan leaders can learn from the places across the country that are ahead of the curve when it comes to integrating immigrants and making the most of their economic contributions.

In our new book, The Metropolitan Revolution, we highlight one such effort in Houston, one of the most diverse metros in the country. Neighborhood Centers Inc. is a network of 21st century settlement houses that has embraced Houston’s diversity and is providing thousands of new immigrants the services they need to succeed in the city’s vibrant economy. Neighborhood Centers offers English language training, childcare, financial and banking assistance and many more services that provide a ladder to the economic mainstream.

In 2012, Neighborhood Centers’ efforts to help immigrants and other low-income people prepare their federal tax returns brought $41 million back to the Houston economy in the form of tax credits and refunds, money that will send children to school and provide seed money for small business. They also helped 350 people become US citizens, which, according to one study (pdf), paves the way for higher earnings in the short run and wages that rise faster over the long term.

In New York City, home to the nation’s largest immigrant population of more than 5.3 million, the mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs focuses on both community integration—via English language classes, NYPD liaisons, civic engagement programs—and on economic integration, by providing tools to support immigrant-owned small businesses with legal and financial advice and by linking high-skilled immigrants with suitable jobs.

Either of these efforts could inform an immigrant integration or outreach initiative in a metro. Metropolitan leaders should see what is happening in similar communities, and copy the best of what works.

Finally, metropolitan leaders need to be ready to move once federal immigration reform does pass, in whatever guise. Our colleagues Audrey Singer and Jill Wilson have identified many questions that metros may have to answer about the on-the-ground impact of the federal bill, including the following:

- How will local governments and other organizations help implement the legalization rules, which may require biometric identifications, background checks, and English and civics courses, among other things?

- How will local DMVs handle a potential influx of new requests for driver’s licenses?

- How will the shift to more employment-based immigration (as opposed to family-based immigration) affect which immigrants move to which communities?

- What support to local employers need to adjust to new provisions like electronic verification of immigration status?

Local leaders need to reach out to their networks of business, civic, religious, educational, and other institutions to answer these questions, so that they understand who has the capacity and skill to take on the post-reform challenges.

This is immigrant policy from the ground up. Smart metro leaders recognize immigration, and the eventual immigration reform bill, as an opportunity. Places that work hard to educate and integrate their immigrant families will set themselves up for success. Places that ignore them—or wait until Washington acts first—will not.