How five great leaders dealt with crisis, and what we can learn from them

In the early 2000s, Nancy Koehn was socked with one personal blow after the next within a three-year period: Her father dropped dead suddenly. Her husband walked out and a terrible divorce ensued. And she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

In the early 2000s, Nancy Koehn was socked with one personal blow after the next within a three-year period: Her father dropped dead suddenly. Her husband walked out and a terrible divorce ensued. And she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

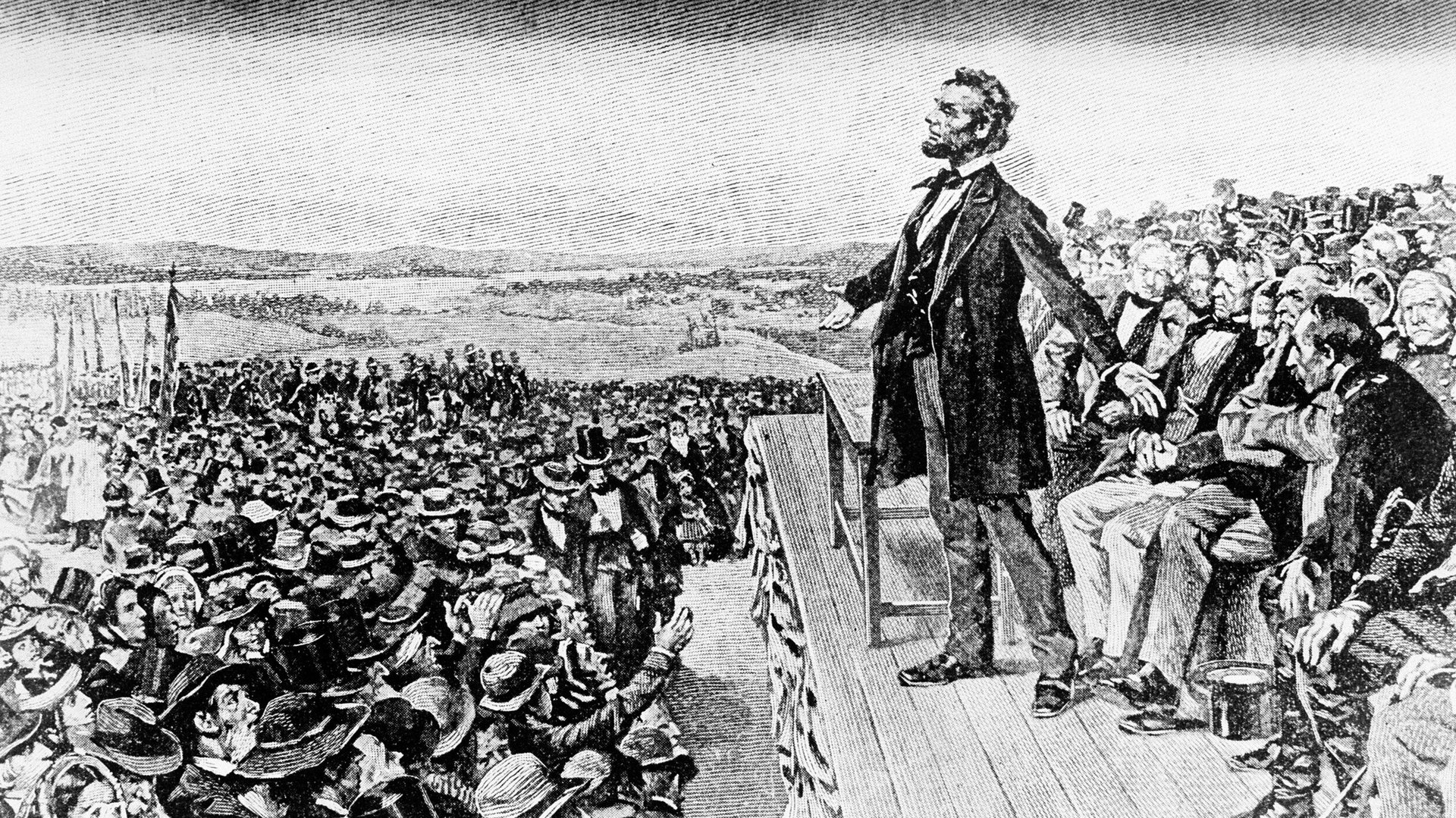

As these “big hunky blocks” of her life were falling around her, the business historian says she reached for the collective writings of Abraham Lincoln.

“I was feeling vulnerable, and it was a personal search for some sort of clarity and redemption,” explains Koehn, the James E. Robison professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. “I was struck by all that Lincoln was carrying, and I thought, ‘Nancy, you think you have problems. Look at Lincoln!’”

Koehn set out to write a book about the former president, inspired by his remarkable leadership as he persevered in his fight against slavery. He did so despite the weight of many Civil War losses on his shoulders and personal tragedies, including the death of his son. But, after four years of “sniffing and snooping,” it occurred to her the world didn’t need another Lincoln book.

Koehn realized she had more to say about how great leaders were made, and Lincoln was just one shining example. She decided to pull into the fold other leaders who had gripped the attention of her students in her courses at HBS: polar explorer Ernest Shackleton, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, Nazi-resisting clergyman Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and environmental crusader Rachel Carson. The result, about a dozen years in the making, is Koehn’s book Forged in Crisis: The Power of Courageous Leadership in Turbulent Times, which is being published this week.

Each of the extraordinary people Koehn chronicles found themselves at the center of a great crisis. Shackleton was stranded on the ice with his men in the Antarctic. Lincoln was on the verge of seeing the Union fall apart. Douglass, an escaped slave, was dodging capture by his former owner. Bonhoeffer was secretly working to bring down Hitler while attempting to evade his own arrest by the Nazis. Carson was racing to finish a book about the dangers of pesticides before cancer silenced her.

Each person faced long odds of success, each was filled with fear, dread, and uncertainty, and yet each found the inner strength—rooted deeply in the need to fight for the greater good—to carry on.

The book urges readers to peer into the past and find inspiration from five people who managed to accept their failures, steady themselves, and overcome great obstacles to make their mark. It’s a call to action for future leaders: “Read these stories and get to work,” Koehn says in her introduction. “The world has never needed you and other real leaders more than it does now.”

Yet, the book is also more than that. Like a warm cup of tea on a cold, rainy day, it’s an antidote to those times when we all feel overwhelmed by our own struggles—work-related or personal. Koehn herself certainly knows that feeling.

“Lincoln taught me a great deal about the possibilities of growth in the midst of crisis,” says Koehn, whose research focuses on how leaders craft lives of purpose, worth, and impact. “When I’m scared or confused or besieged with problems, I think, ‘What would Bonhoeffer do?’ I’ve had other people say to me, ‘Here’s what I was dealing with, and this is why Rachel Carson really spoke to me.’ The ability for a story from history to help someone when they are emotionally vulnerable and confused is deeply gratifying. Each of these people triumphed—after they failed—and they made a great difference in the world. We can learn a lot from their stories.”

In this interview with HBS Working Knowledge, Koehn delves into the many leadership lessons readers can take away from the five subjects she profiled.

Dina Gerdeman: As a slave, Frederick Douglass feared his master, but then something shifted in him the day he decided to physically fight back. You say that confronting your fears head on allows you to find your core strength. I imagine this is as true for the people you write about as for the entrepreneur looking to start a business?

Nancy Koehn: When we’re dealing with our worst fears, it’s hard. I call it the 2 am cold sweats, where you think: How am I going to get through this? Every leader knows these moments, and the people in this book experienced those.

What’s interesting about this critical moment for Douglass: You see a man who’s been made a slave, and he’s scared of [the overseer], but he’s not going to succumb this time. He steps into it. Bonhoeffer talks about killing himself, then learns how to step back from the edge of caving in. He is quaking in his boots when he is interrogated [by Nazis]. And the next time, he’s a little less scared. Lincoln talks a lot about doubt and despair, but he learns how to manage it.

These people squared their shoulders and took a series of small steps into the fear. Each step you take makes you a little stronger and a little braver, and that means that the next baby step is easier than the one before. The people in my book keep on keeping on and walking into the fear—until the winds have died down and they know the storm has passed for them.

At times, leading an organization is about an ongoing encounter with one’s own fears and the fears of one’s people. A lot of leaders who take on the amount of responsibility and accountability that goes with being the CEO of a major company will encounter fear and have to figure out how to deal with it.

Some of our alumni [who are business leaders] have said, I knew it was going to be really hard, but I took that first step and the next step, and after a difficult journey, the impossible was made possible. They understand that ordinary people can make themselves capable of doing extraordinary things.

It’s not easy. Turbulence is all around us, and that creates more fear. I think of Merck CEO Ken Frazier, who resigned from the president’s manufacturing council because he didn’t believe the president was speaking with integrity [during his initial failure to condemn white supremacists]. I can imagine Ken Frazier had some anxiety about that. But he did it anyway.

Gerdeman: You say in the book that great leaders live by “right action.” Can you explain what you mean?

Koehn: If you read all five stories, you realize that part of what fuels each of the protagonists, when they’re most vulnerable or confused or in a fog of doubt, is the mission. The goodness of what they’re trying to do gives them each the energy to take the next step. It’s not like they wake up and are born with the genes of Jesus or that they have been endowed with a prophet’s sense of purpose.

Shackleton is chasing fame when he goes to the Antarctic. Carson wants to be a best-selling author. It’s a narcissistic quest that gives way to the realization of a larger moment and a sense that they can make a worthy difference to other people. They stumble onto the goodness of their contribution and the possibility of service to others, and the narcissistic quest disappears in that discovery.

Carson realizes: “DDT is a big deal. I’ve got to wake people to the dangers here.” Shackleton says, “I’ve got to save my men.” Lincoln says, “We can’t have this loss of life in the war without cutting out the cancer of slavery.”

I say to my students: “Don’t give up looking. You have a bigger purpose, and the search for that purpose can take you somewhere astounding.” Our millennial students and our alumni want to answer that call. So many values we hold dear as a nation are up for grabs right now in a newly prominent and frightening way, and this is a call for action.

Gerdeman: Shackleton is an example of someone who worked quite a bit on team-building. He made a point of connecting personally with his men, and he also knew the way he carried himself could make the difference in whether his team survived. Can you talk about why team-building is important?

Koehn: Without Shackleton’s ability to foster cohesion among his team, those folks wouldn’t have survived. It started with how he selected people for his team. He hired for attitude and trained for skill.

And then he knew how to manage his worst enemies, the naysayers. He couldn’t fire the people who doubted him and spread pessimism and negativity because they were all on the ice together, but he kept the naysayers close, so he himself could contain them. At the same time, he was managing the energy of his team in other ways. Once the ship had been down for months and supplies were running low, for example, Shackleton ordered up double rations to raise the men’s spirits by feeding them. Each evening after supper, he walked around to the men’s tents at night to play cards or tell stories.

All of Shackleton’s actions were intended to make his men feel they were a part of this band of brothers that together could not fail. And, when he himself walked out of his tent in the morning, he made certain to appear confident and to show up with positive energy, even when he harbored his fears and doubts himself.

Gerdeman: Even when Bonhoeffer was in prison, he woke up at a certain time, exercised by pacing his cell, and pinpointed certain times for reading and writing. What is the importance of focus and discipline—and is it harder today with all of our distractions?

Koehn: We certainly have distractions, but I don’t think it’s necessarily tougher to focus today. When Lincoln was president, for example, he had hundreds of citizens lining up at the White House to speak to him, many with issues that needed executive attention. His office was at the center of the war effort and he had no joint chiefs of staff, so he had scores of military issues swirling around him at all times. He also had to deal with constant political pressures—in Congress and with the states. While all this was happening, Lincoln was the focal point for enormous amounts of vitriol and hatred stirred up by the war. He didn’t have Twitter or television, but the 16th president kept in close touch with politicians and ordinary Americans through his speeches, letters to editors, individual communications to citizens, including his weekday office hours [in which anyone could line up to see the president], and ongoing visits to the battlefields. So we may think modern leaders have a lot coming at them, but it’s hard to argue the leaders in the past, like Lincoln, were not similarly besieged.

There’s a great seduction to our iPhones. I often say to executives that they’re like our lovers. We keep them close; we depend on them; we even stroke them; we’re anxious if we’re not near them. Most of us have some small or large addiction problem with our technology. But, at some point, leaders need to turn away from their inboxes and newsfeeds and twitter notifications and realize that they don’t contain all the answers, and that they often prevent us from seeing a range of important things.

One of the other critical lessons in the book related to focus is that making a big, worthy difference is never about the 10 things in front of a leader; instead, it is about one or two or three key issues. And with all the stuff coming at leaders so much of the time, we have to be reminded of that.

Before he became president, Lincoln gave a lecture to law students saying that if he could swing the jury to one or two of the points that really mattered to the case, he could give away the rest of the points to the opposition. This makes for smart negotiation tactics—disarm your opponent by relinquishing the points that you don’t need to keep while holding onto the essential issues—but it is also a leadership mantra.

Gerdeman: The leaders you write about have these “gathering periods”—times when there may not be any great outward progress, but they gather their tools and experiences and find the strength to take the next step forward.

Koehn: Yes, all of the people in this book had these periods in which they were not checking off a lot of items on life’s to-do list, and they weren’t seeming to make a great difference in the external world. Lincoln spends six years practicing law and keeping himself informed about politics. He is watching the cauldron of slavery gather to a rising boil, but the resume isn’t crowded in those years. Shackleton is waiting for the ice to break up. Carson is working at the Fish and Wildlife Service, but not accomplishing a great deal on what today we might call her bucket list.

What’s happening to these people during these moments? They are investing in themselves. They’re learning a great deal about their thinking and possible contribution to the great events of the day. Those periods of not accomplishing things externally were, instead, about building their equipment inside—emotionally, intellectually, and in some cases spiritually—to be ready for their moment. They’re not losing sight of the big picture and the stage on which they’re going to make a big difference. These are people who commit to getting better from the inside-out.

These gathering years are important for our millennial students to understand. Your moment doesn’t always have to happen in a dramatic, made-for-the-movies way when you’re 27. You prepare yourself for the next big move you’ll make, but you can’t make that move until you understand the stage.

Gerdeman: You talk about Rachel Carson’s struggle to find that work-life balance—something many working women relate to. It’s important for leaders to take care of themselves, right?

Koehn: Rachel was so careful about understanding the natural world and bringing this understanding to a larger audience. She understood organisms and what made them thrive. But she didn’t turn that same care and attention to herself. She gave and gave and gave to others and to her work without consistently feeding and watering herself very well.

Today, we know a lot more now about the relationship between emotional duress and diseases like cancer than medical science did in the early 1960s when Carson was writing Silent Spring, her magnum opus. But, I will always think that Rachel’s battles with breast cancer were partly related to all the years she worked so hard and did so much giving without much refueling. For several decades, she was the primary breadwinner for her family as well as being an important caretaker for the same people.

In some ways, Carson’s dilemma was a particularly female one. Like many women, she kept giving and supporting and fluffing and buffing the people she loved. She focused on that and often neglected the fuel she herself needed. Sometimes women need to put up boundaries and say, “No, I can’t do that” in the interest of taking care of themselves. I think women often have a harder time doing this than men. The feeding and watering and protecting of one’s energy is important. Mothers are great leaders, but every mom knows what it’s like to run out of gas.

Recently, I was at dinner with a dozen high-ranking executives and someone said, “If you as the leader flag, everything flags. Everything becomes vulnerable.” It’s really important to remember that, especially for women leaders.

Gerdeman: You mention that charisma and aggressiveness—two traits we often associate with important leaders—aren’t essential to making a big impact.

Koehn: The stories in this book demonstrate that charisma and aggressiveness aren’t essential characteristics for courageous leaders. Carson and Bonhoeffer were not aggressive. Their cause and their sense of integrity created energy around them that was compelling for others. Both of these people were also deeply reflective. Carson was shy. Bonhoeffer was a man of fewer rather than many words. But these people motivated others to do the hard stuff and work from their better selves.

In this context, one thing these stories can do is expand our idea of what a great, effective leader is. We’re wedded to thinking that if someone is hard-charging, quick-acting, compelling, and charismatic, those are the people we must follow and elect and support. That’s not the whole story by any means.

Lincoln was a good public speaker and people wanted to be around him, but he was slow-moving. He was hardly hard-charging. People called him a country bumpkin in his early years in the White House. He often looked at every angle of a decision before making a choice. When the stakes were really high and the emotions around an issue were charged, Lincoln often did nothing in the heat of the moment. And this is a vital lesson for our time. Sometimes doing nothing is the most powerful something we can offer in service to our ultimate purpose. If we’re too aggressive and act quickly, we can sabotage our mission or make the situation more incendiary than it needs to be.

Gerdeman: You say in the book that we live in a moment when our collective faith in government, business, and religion is waning. Do you think people have a growing concern that we’re experiencing a void in great leadership?

Koehn: There’s no question we have a leadership vacuum here. It’s not confined to the executive wing. It’s also in Congress and across the political spectrum.

This void is partly a result of the lapses of integrity and judgment and decency that contributed to the financial crisis of 2008—and regrettably, many of these lapses were never made right, just as many of the people responsible for them were not held accountable. And this lowered standards for people in power in a range of organizations.

At the same time, we voters have become seduced by what I call “leadership bling”: by who’s on the red carpet, who got rich quick, by who seems sexy and full of charisma and decisiveness. All this interest in celebrity and wealth has kept us from focusing on what really matters in the people we elect and follow and that is people of strong and decent character, people who want to serve others and advance the collective good.

As citizens, we need to pay closer attention to these kinds of priorities, and this means asking different questions, such as, how did a given individual respond to adversity? That will tell us a lot about whether that person’s master is the people or his or her own self-interest. We need to be much more demanding of the people we choose to be our leaders.

Gerdeman: And that’s something business leaders should realize as well?

Koehn: Yes, courageous leadership is courageous leadership. If the leader of an organization can find a worthy purpose, you inspire the people around you to personify the kind of behavior needed to accomplish that purpose. And this makes the company run better and the country run better.

One of the things I have learned writing this book is that leaders come in all shapes and sizes. School librarians can be effective leaders. So can firefighters and chemo nurses and CEOs. And as our collective disillusionment with our national officials grows, so, too, does our search for real leaders in other places and other roles.

We very much want to believe in courageous leadership. At a time when many of our leaders are showing up as petty and divisive and disrespectful, the call to lead with integrity and honor could not be louder.

One of the messages of this book for executives and the general readership base is: This is your moment to step on to the stage and lead from your stronger self, because the world needs you now like it’s never needed you before.

This article was republished with permission of Harvard Business School Working Knowledge, where it first appeared.