The incredible story of how the last known work of Leonardo da Vinci was almost lost forever

When Dianne Dwyer Modestini began chipping away at a painted-over and murkily varnished image of Jesus Christ more than a decade ago, little did she know she was restoring the last Leonardo da Vinci work known to the world.

When Dianne Dwyer Modestini began chipping away at a painted-over and murkily varnished image of Jesus Christ more than a decade ago, little did she know she was restoring the last Leonardo da Vinci work known to the world.

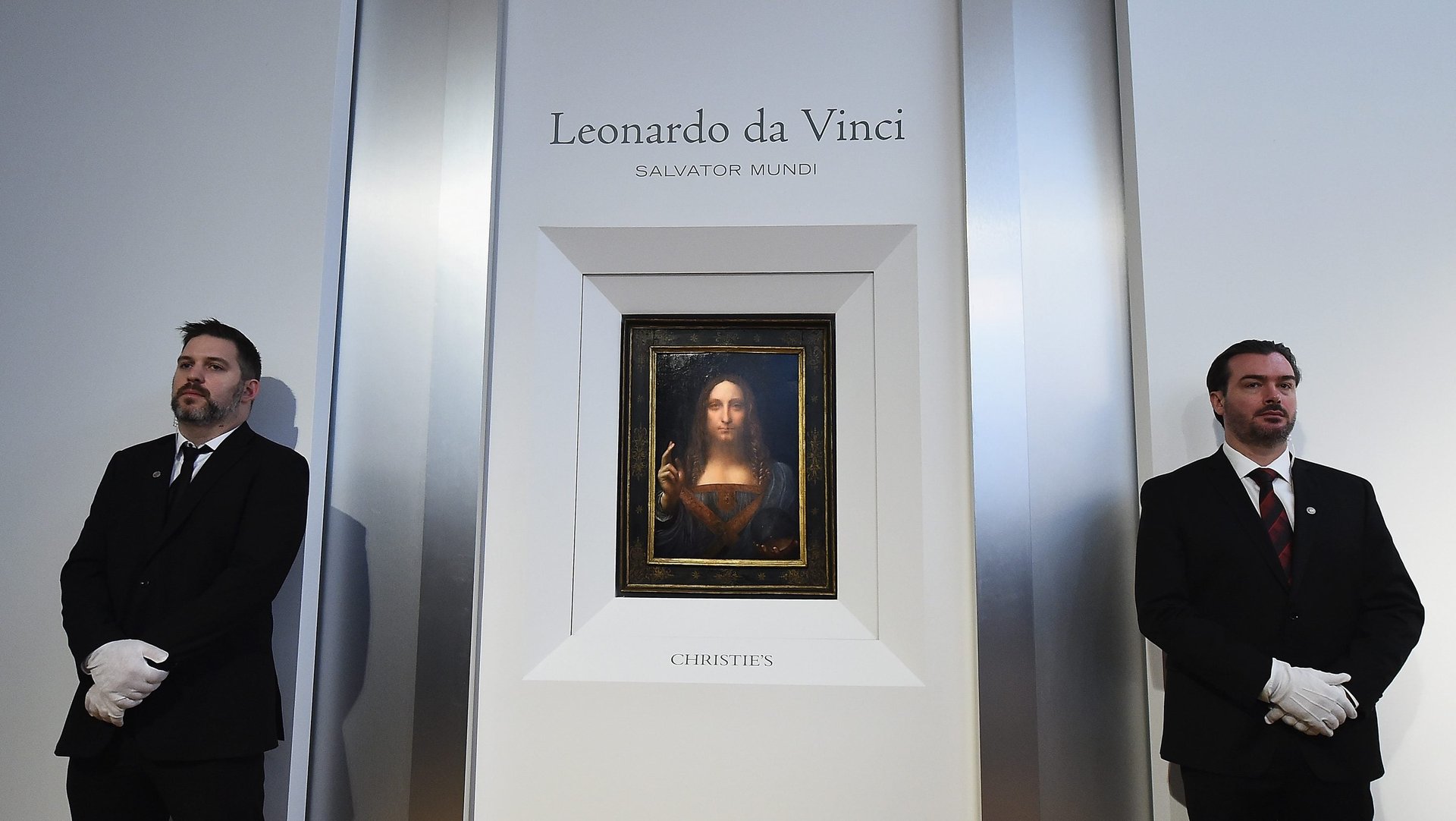

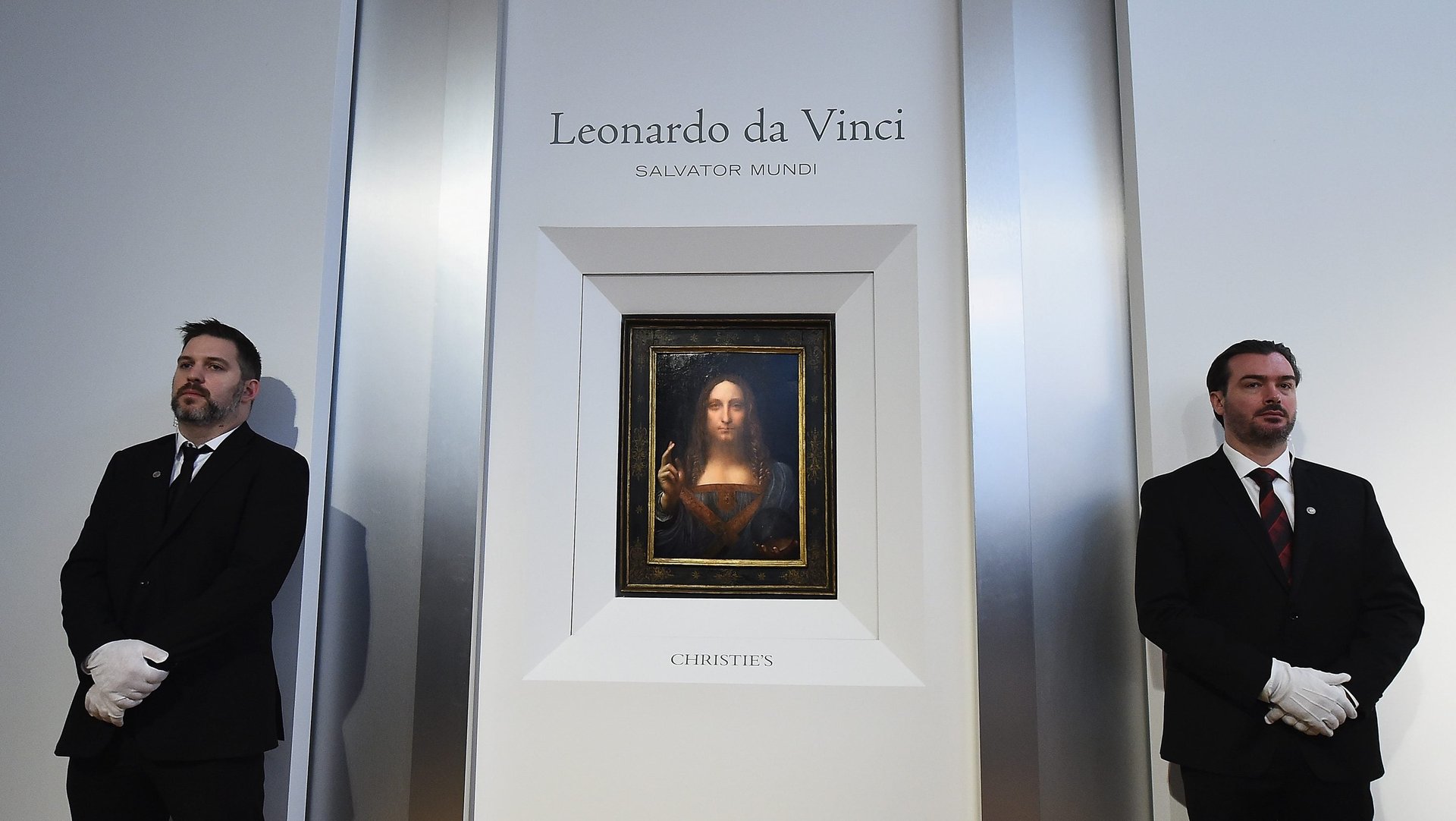

This week, the New York auction house Christie’s, announced that Salvator Mundi (Latin for “Savior of the World”) will be offered for an estimated $100 million next month. The painting is owned by Russian investor Dmitry Rybolovlev, whose estimated net worth is $7.4 billion and has been mired in many controversies—in the art world and beyond.

While art historians knew Salvator Mundi existed, rediscovering the work had become an elusive dream. In 1958, the painting—not known to be Leonardo’s work—changed hands for a meager $60 at an auction at Christie’s. Then, in 2005, the painting was acquired by a group of art dealers, including Robert Simon, a specialist in Old Masters. The painting had clearly been mishandled, painted over, and shoddily restored with an artificial resin that congealed and turned gray.

After careful analysis, documentation, and restoration by a number of scholars, Simon announced that the work was unequivocally a da Vinci, created 500 or so years ago. The last painting to be discovered and verified as a Leonardo original was in 1909, the Benois Madonna, now on display in the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia. Today, most experts believe fewer than 20 original paintings created by Leonardo exist.

The laborious—at times terrifying—six-year restoration process was led by Modestini, a renowned conservator and professor at New York University. The task of restoring one of the world’s rarest works of art could be daunting. Modestini devised a head-on approach, taking account of the full weight of every decision in the process.

“I wanted [to be sure] that none of my restorations had impinged on the original, that I had not done too much, because old pictures have to look old—if you take out every crack, every spot, every anomaly, they can easily look like a reproduction,” she told CNN in 2011.

When the restoration was finally complete, Modestini says she fell into withdrawal, depression, and separation anxiety from seeing the painting move on. She likened the end of her restoration efforts to an emotional break-up: “It was a very intense picture and I felt a whole slipstream of artistry and genius and some sort of otherworldliness that I’ll never experience again.”

In 2011, the painting was shown at the National Gallery in London. Two years later, it sold for $80 million at a Sotheby’s auction to a well-known Swiss dealer, Yves Bouvier, The New York Times reported. Soon after, the painting changed hands, with Rybolovlev saying he paid $127.5 million. (The traders who originally sold the painting to Bouvier threatened to sue Sotheby’s, believing they were unintentionally misled to favor a prized client and give up close to $50 million in value. Rybolovlev, meanwhile, accused Bouvier of fraudulently overcharging him in the purchase of 38 paintings, for as much as $1 billion in profits, the Times reported.)

Others will soon get to revel in the sight of Salvator Mundi, which will be on exhibit in Hong Kong, San Francisco, and London over the next few weeks before returning home to New York.