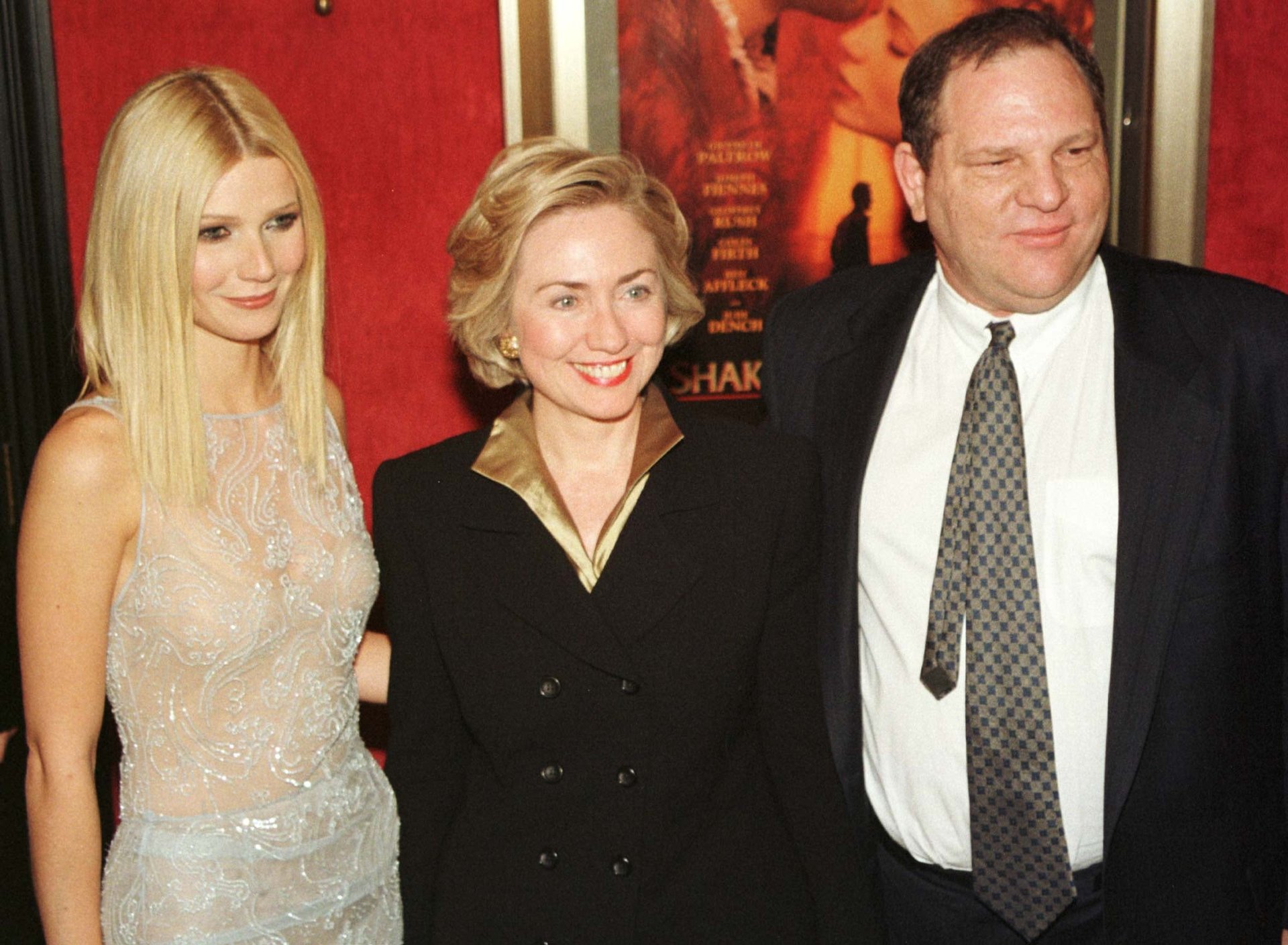

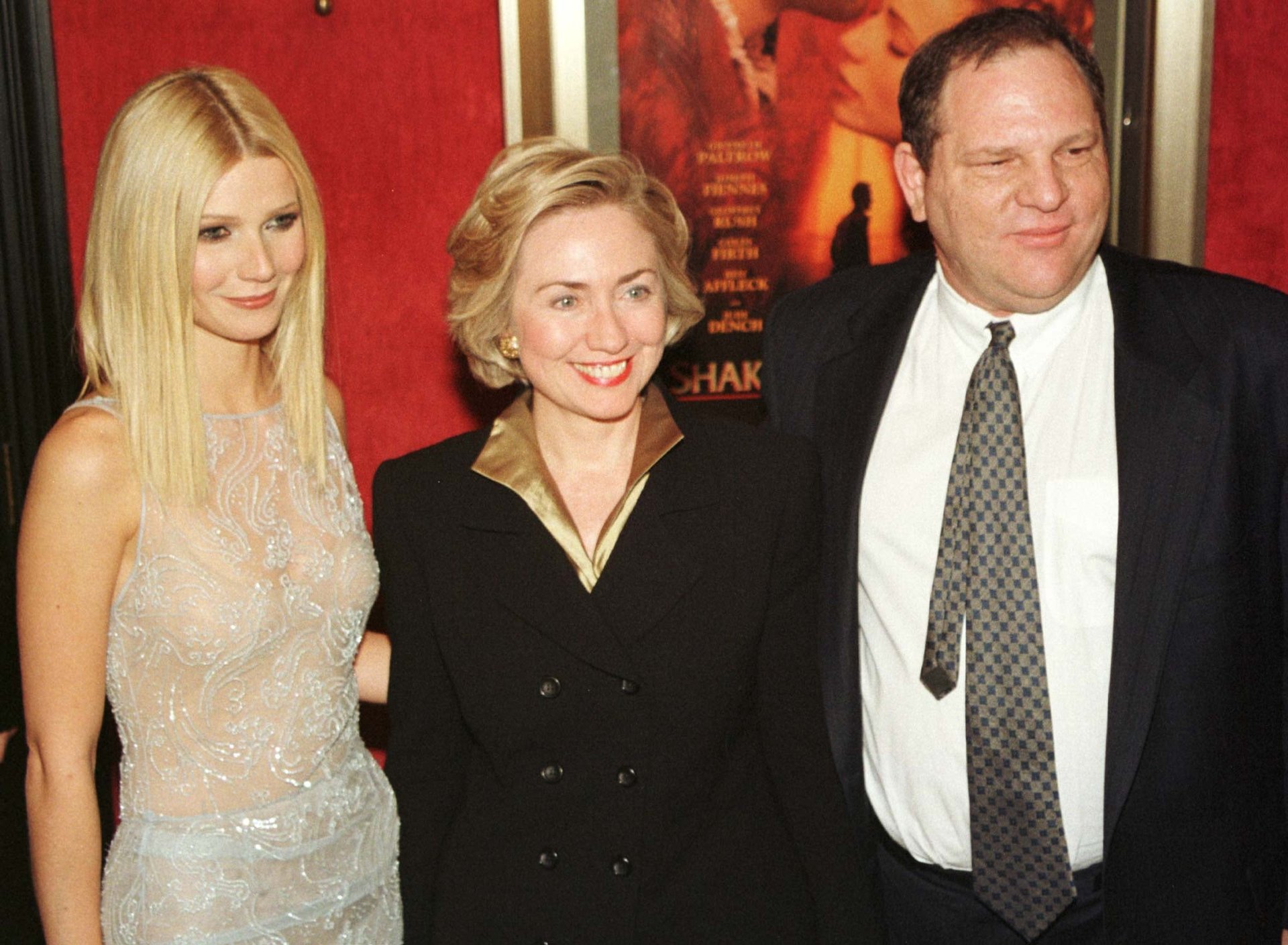

Bill Clinton, Harvey Weinstein and how abuse allegations echo across decades

The fallout from a New York Times (paywall) investigation revealing explosive allegations of routine sexual harassment by movie producer Harvey Weinstein is still reverberating, with Amazon’s entertainment chief, Roy Price, the latest to see his job in jeopardy.

The fallout from a New York Times (paywall) investigation revealing explosive allegations of routine sexual harassment by movie producer Harvey Weinstein is still reverberating, with Amazon’s entertainment chief, Roy Price, the latest to see his job in jeopardy.

Accusations of sexual harassment or misconduct, of course, have been reported over the years in the entertainment world and on Wall Street. The tech industry, too, currently is embroiled in its own scandal. Allegations of powerful men taking advantage of and preying upon women trying to get ahead aren’t new.

Let’s compare, for instance, the clandestine police recording of Weinstein, 65, seeking to have model Ambra Battilana Gutierrez, then 22, to go to his New York hotel room with him in 2015 with what former president Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, allegedly said and did to a 24-year-old Paula Jones in 1991. The cases show how accusations of inappropriate advances and touching often are not enough to establish harassment or any other claim, even in instances when the power imbalance is extreme.

Parallels, decades apart

Investigators taped Weinstein in an attempted sting after Gutierrez told police that he had invited her to his office the day before for a business meeting and asked if her breasts were real before touching them. Here is an excerpt from the hotel-room tape, as reported by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker:

Weinstein: Please, I’m not gonna do anything. I swear on my children. Please come in. On everything, I’m a famous guy.Gutierrez: I’m feeling very uncomfortable right now.

Weinstein: Please come in now. And one minute. And if you wanna leave, when the guy comes with my jacket you can go.

Gutierrez: Why yesterday you touch my breast?

Weinstein: Oh, please I’m sorry just come in. I’m used to that.

Gutierrez: You’re used to that?

Weinstein: Yes, come in.

The Manhattan district attorney’s office opted not to file charges of sexual abuse, the New Yorker said, and, according to Farrow’s sources, Gutierrez later accepted a payment from Weinstein in return for a nondisclosure agreement. (Overall, Weinstein denies any allegations of non-consensual sex and retaliation for refusing his advances.)

According to Jones’s 1994 sexual-harassment lawsuit, here’s what Jones, who was a state government employee, said Clinton did:

Plaintiff states that upon arriving at the [hotel] suite and announcing herself, the Governor shook her hand, invited her in, and closed the door…Plaintiff states that the Governor then “unexpectedly reached over to [her], took her hand, and pulled her toward him, so that their bodies were close to each other.” She states she removed her hand from his and retreated several feet, but that the Governor approached her again and, while saying, “I love the way your hair flows down your back” and “I love your curves,” put his hand on her leg, started sliding it toward her pelvic area, and bent down to attempt to kiss her on the neck, all without her consent. Plaintiff states that she exclaimed, “What are you doing?,” told the Governor that she was “not that kind of girl,” and “escaped” from the Governor’s reach “by walking away from him.”…Plaintiff states that she sat down at the end of the sofa nearest the door, but that the Governor approached the sofa where she had taken a seat and, as he sat down, “lowered his trousers and underwear, exposed his penis (which was erect) and told [her] to ‘kiss it.‘”

It took Jones, now 51, four years and a slew of bad publicity to reach an $850,000 settlement with Clinton, who denied the allegations. Most of the settlement money went to pay her lawyers. Her marriage broke up. She didn’t get an apology, later left her job, moved to California, and posed nude for Penthouse, citing single motherhood and the need to support two children. In dismissing the case on grounds Jones couldn’t prove damages, the judge called Clinton’s behavior merely “boorish.”

Why accusers often have no recourse

The costs of coming forward to accuse a powerful man are huge. You are likely to have your reputation smeared, your career prospects dimmed, and you may lose your job when he retaliates. For most women, it’s not worth the risks. Easier to complain privately, smile, and move forward. Nor can other supervisors be relied upon to be interested in getting involved—they also depend on that man for their livelihoods.

A court case is particularly dicey. Legally, sexual harassment in the workplace is not the occasional grope, lewd comment, or leer. You either must show sexual favors were demanded to get or keep a job—and you lost it because you didn’t acquiesce—or the behavior is so hostile and pervasive that it hurts your ability to perform your job. According to the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “sexual flirtation or innuendo, even vulgar language that is trivial or merely annoying, would probably not establish a hostile environment.” And most men in power know this. (And, of course, harassment does not have to be between people of two different genders.)

Why wouldn’t a company take action? If the man involved is as powerful as Clinton or Weinstein, the risks to everyone else in the organization are enormous. Clinton’s administration was derailed during the broader investigation by a special prosecutor who included the Jones lawsuit in his probe. Clinton was later impeached and almost lost the presidency. With Weinstein himself fired as co-chairman, his company is now exploring a sale or shutdown. That will put many good, creative people out of work.

Navigating the delicate dance in the workplace between flirtation and harassment has clearly been tricky for men, and for women. That so many, many women have recently come forward in the media to expose entertainment figures and those in technology as sexual predators is extraordinary. It has the potential to remake the workplace for women—and for men.