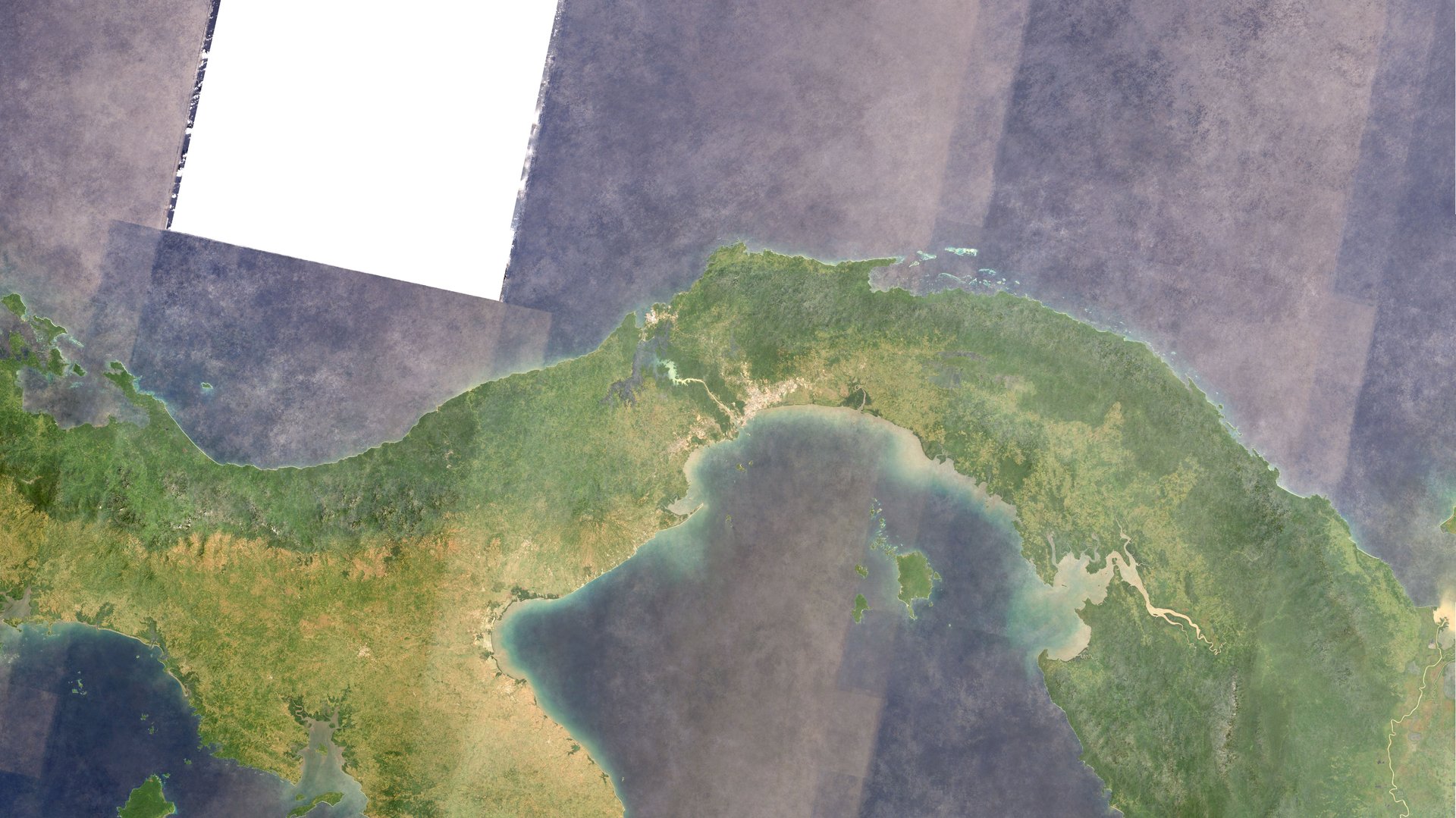

Seven places in the world where global trade could be stopped cold

This article originated in the research for Quartz’s new book The Objects that Power the Global Economy. You may not have seen these objects before, but they’ve already changed the way you live. Each chapter examines an object that is driving radical change in the global economy.

This article originated in the research for Quartz’s new book The Objects that Power the Global Economy. You may not have seen these objects before, but they’ve already changed the way you live. Each chapter examines an object that is driving radical change in the global economy.

The world produces 96.7 million barrels of oil on average per day. Of that, 18.5 million float daily through a water corridor as narrow as Manhattan. Called the Strait of Hormuz, this stretch of water connects major oil producers, including Saudi, Iraqi, Emirati, and Qatari wells, to the rest of the world. If the Strait shut down abruptly, as it did during the Gulf War (and as constantly threatened by Iran today), the disruption would cause ripples in jobs and costs of goods across the global economy.

The Strait of Hormuz is what’s known as a “chokepoint.” It is one of seven extremely narrow water corridors that big ships tend to use as shortcuts. It is faster and cheaper to travel from the Middle East to Europe through the Suez Canal (another chokepoint) than by circling Africa, for example. But since chokepoints are surrounded by land, and therefore vulnerable to regional and national politics, they are as risky as they are useful.

In addition to the Strait of Hormuz and the Suez Canal, there are several other commonly-traveled chokepoints in the world; the US Energy Information Administration also names the Mandeb Strait, the Danish Straits, the Turkish Straits, the Strait of Malacca, and the Panama Canal as the most important to global energy security. Roughly six out of ten barrels of all oil produced worldwide travel by sea, and are likely to pass through these tight spots.

Below, striking satellite images of these water corridors serve as reminder of the fragility of those global flows.

Strait of Hormuz

The main gateway for six of the 15 largest oil producers in the world, the Strait of Hormuz has been consistently under threat of disruption over the past decades. Earlier this year, Iranian vessels approached an American destroyer here, causing it to fire warning shots. Sometimes, the Iranian government or Iranian politicians threaten to close the strait, limit shipping, or charge for passage—“choking the throat of the West,” as one political party leader in Iran put it in 2010.

If the Strait of Hormuz were blocked for just one month, the US would lose between $10.6 billion and $14.7 billion in GDP per quarter, according to studies from 2007 and 2011. Only Saudi Arabia and the UAE could still move oil out of the region, through overland pipelines.

Strait of Malacca

After the Strait of Hormuz, the busiest water corridor is the Strait of Malacca. This narrow passage between Indonesia and Malaysia connects the Indian Ocean with the Pacific Ocean—or Gulf wells with Asian economies.

More than 80% of the oil that arrives to China by sea travels through the Strait of Malacca. Here, the biggest dangers to passage are congestion and pirates. Because it is even narrower than the Strait of Hormuz, there is also the danger of collisions and groundings.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal, which connects Asia with European and American economies, is an important source of money for Egypt. But the Suez Canal has been losing ships to the Panama Canal over the past year. After a nine-year and multi-billion dollar expansion, the Panama Canal can fit some of the larger ships that before would pass only through the Suez on their way from Asia to the Atlantic.

Mandeb Strait

The Mandeb Strait connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean, with Djibouti and Eritrea on one side, and Yemen on the other. Somali pirates were once been a common threat for tankers in the area, but in recent years, the number of pirate attacks has dropped due to safety measures, like naval task forces that patrol the area, ran by the US, NATO, and the EU, among others.

The economic cost of piracy in the broader West Indian Ocean dropped from $7 billion in 2010 to $1.3 billion in 2015. However, in early 2017, pirates did manage to hijack an oil tanker close to Somalia for the first time in five years.

Danish Straits

There are three Danish Straits connecting the North Sea and the Baltic Sea in Scandinavia: Øresund, between Copenhagen and Malmö; the Great Belt; and the Little Belt. Together, these make up an important path for oil coming from Russia and into Europe.

Turkish Straits

The Turkish straits are the extremely narrow Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits. These connect Russian and Central Asian wells with Europe. The narrowest section of the Turkish straits is only half a mile wide. On top of that, the course is sinuous and crowded with ships, making navigation more dangerous than in some other water corridors.

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal connects the Pacific with the Atlantic ocean. Though it is the most famous, it receives the smallest amount of oil of the seven chokepoints.