The scientist who traveled the world in a shipping container to study cold storage

Shortly after graduating from Cornell University, Barbara Pratt was hired in 1977 by shipping company Sea-Land (now Maersk) to build a laboratory inside a standard shipping container. For years she traveled around the world inside of it, figuring out how best to ensure that perishable goods remained fresh on long journeys. Today, Pratt directs refrigerated technical services for Maersk North America.

Shortly after graduating from Cornell University, Barbara Pratt was hired in 1977 by shipping company Sea-Land (now Maersk) to build a laboratory inside a standard shipping container. For years she traveled around the world inside of it, figuring out how best to ensure that perishable goods remained fresh on long journeys. Today, Pratt directs refrigerated technical services for Maersk North America.

The following has been condensed and edited for clarity:

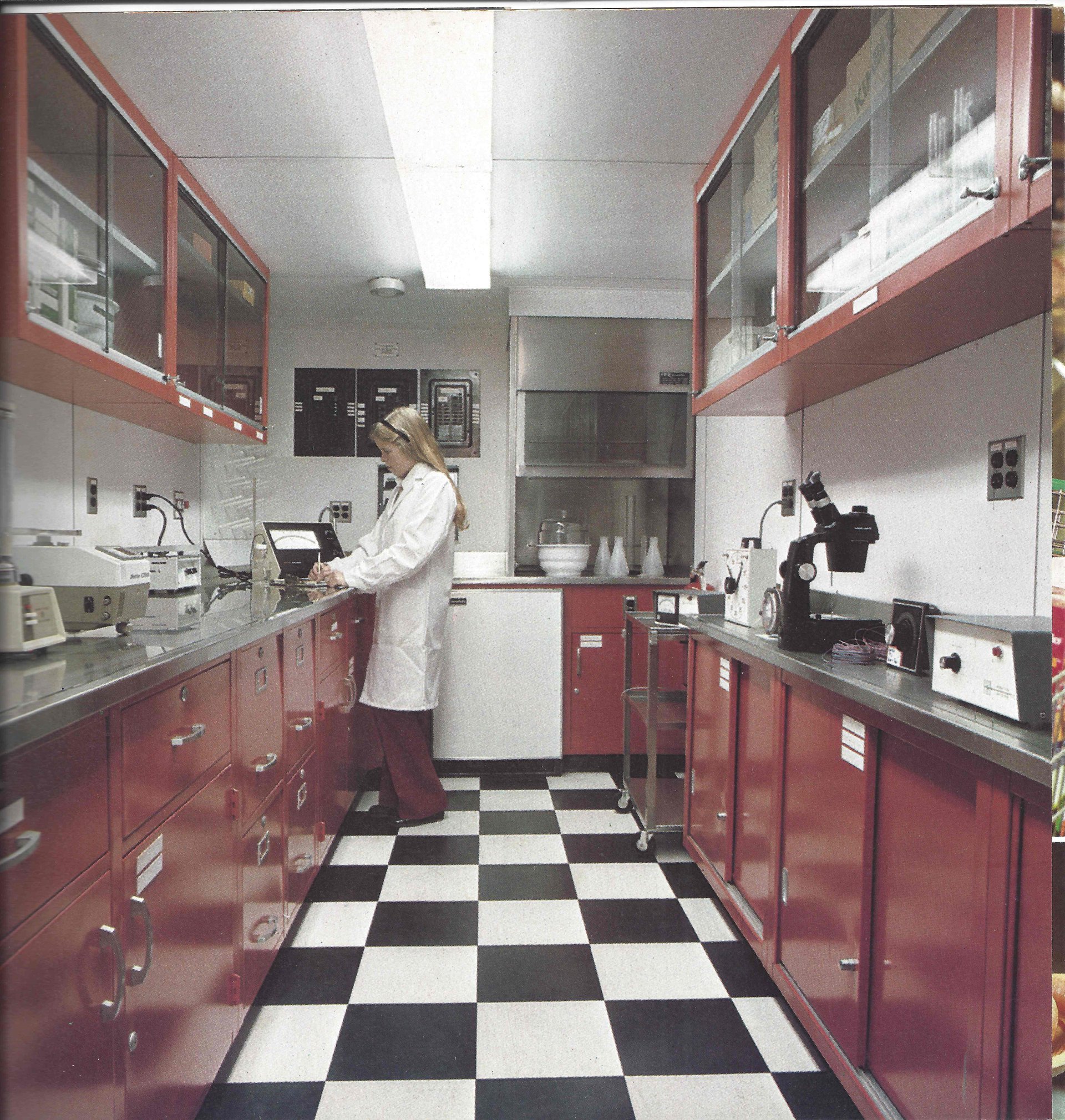

“The laboratory we built was three different compartments: It had what we called an engine room where we had a diesel fuel tank, a diesel generator for power, a water tank, a hot water heater… We had a laboratory section which was in the middle which had your typical equipment but it also had things like a gas chromatograph, a computer, a fume hood, and a microscope—those types of things. And then we had an office section which had bunk beds in it, and a couple of desks and cabinets, a microwave, and a refrigerator.

“Once the laboratory was completed, our first project was working trying to improve the turnout of cocoa beans that were moving from the Dominican Republic to United States. The beans themselves were ending up moldy, had mold on them by the time they got to destination or were put in the warehouse.

“What happens typically is when the sun comes up the temperature increases inside a dry container, that would create a mini oven, and that draws the moisture out of the beans…And what happens when sun goes down at the end of the day, the water then condenses out of the air because the air temperature changes. It would then become water droplets [and] drop onto the bags of cocoa beans, and when you have excess moisture you would then have mold growing.

“We ran a number of tests, and the end result was we came up with a new container design which ultimately was patented, which provided some paths of ventilation, and helped improve the out-turn of the beans.

“Over the next number of years we worked on various different commodities—almost any commodity that moves today: We worked on pineapples, watermelons, tomatoes, peppers, bananas, all kinds of perishables, trying to see if we could extend the shelf life of those products and carry them, say, for two weeks’ transit, instead of one.

“Part of the reason ages ago we had to stay in the container was the unknown reliability of the computers that we were working with at the time. Today, with the state of the industry and the microprocessors that exist today, it’s possible to monitor what’s happening remotely—whereas I had to stay with the containers to monitor what was going inside them when they were only 20 or 30 feet from me, today that can all be done remotely. The use of microprocessors and computers gives us the ability to analyze and figure out what’s going on with a lot more power than what we used to have.

“In the future, I think that there’s going to be a continued focus on quality, on wanting to know if there was a problem with something, being able to react faster, being able to know what to do. For example, if you were planning on moving into a market and holding the product there for four months, if you you know that there’s a problem with your product, maybe you move it into the market faster and sell it in the first month instead of four months later. I don’t think that will be true for every commodity and I don’t think it will be true for every single shipper. Some of the higher cost items like pharma, they have been moved by air, now they can move some on the water because they can monitor these remotely, and there’s GDP regulations and food regulations that are in existence and are being evolved and the AI.

“When it comes to the consumer, maybe they’re okay with only eating grapes for six months of the year, but I think the consumer over the last 20 years has got used to going to the store and getting more than pickles, potatoes and dried meat. They’re used to fruits and vegetables—they want fruits and vegetables—and their economies are such that they can afford the fruits and vegetables. There are some economies that want more protein, and those markets are going to need to be balanced with the cost it takes to get the products to markets.

“Maybe 98% of commodities we move today move without [damage] claims. It’s the last 2% that I’m excited about working on.”

This interview is an extended version of a piece featured in Quartz’s new book The Objects that Power the Global Economy.