A spider-obsessed artist is collaborating with MIT to spin the architecture for climate change

Inside a dark exhibition hall at the Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, South Korea, a gigantic spider is crawling along the web she has built with her own silk threads inside a cubed frame. The spinning process and the sound of her creation are amplified by a microphone and the image is projected on the wall behind. The eerie installation could well be the perfect prop for Halloween, but according to its creator, Argentine artist Tomás Saraceno, we have a lot to learn from spiders—including, possibly, how to live with climate change.

Inside a dark exhibition hall at the Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, South Korea, a gigantic spider is crawling along the web she has built with her own silk threads inside a cubed frame. The spinning process and the sound of her creation are amplified by a microphone and the image is projected on the wall behind. The eerie installation could well be the perfect prop for Halloween, but according to its creator, Argentine artist Tomás Saraceno, we have a lot to learn from spiders—including, possibly, how to live with climate change.

“These complex spider webs help us understand that we are part of this cosmic web,” the Berlin-based artist told Quartz, speaking about the large-scale work Cosmic Dust Installation featured in Our Interplanetary Bodies, his first solo exhibition in South Korea running until March 25, 2018.

Born in 1973 and trained as an architect before becoming an artist, Saraceno is known for creating artworks inspired by spiderwebs—and often made by actual spiders, thousands of them. Nearly a decade ago, he set up a spider lab in his three-storey studio in southeast Berlin near the Spree River to study spider architecture. It is a place that nearly a hundred spiders call home, and he looks at their behavior and creations for inspiration for futuristic architectural structures that can help humans live in a climate-changed environment.

Arachnologists have praised his work for “expanding the horizons of scientific research,” with his approach of making photogrammetric scans of spider habitats in order to construct large three-dimensional models of them. Bruno Latour, a French anthropologist who focuses on science and technology, said that for Saraceno to achieve his artistic aims, he had to first “push the frontier of spider science.”

Saraceno’s enthusiasm for spiders, and the possibilities they suggest, is backed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was the inaugural visiting artist at MIT’s Center for Art, Science and Technology (CAST) and has an ongoing residency to collaborate with scientists there. MIT describes his work as drawing on physics and aeronautics, and says his biospheres share attributes of soap bubbles and neural networks as well as spider webs. Besides noting their incredible strength, MIT believes spiderwebs have lessons for less tangible networks, such as the internet, for their ability to continue operating well despite local tears and flaws.

Saraceno says that of the more than 40,000 types of spiders, about two dozen of them are social and without hierarchy, meaning that rather than destroying existing webs, these spiders build new structures on top of existing ones, and live there. The installation on show in South Korea is built by one of them, a species known as Nephila, or commonly known as the Golden Orb Weaver, common in warm regions from Asia to Australia, Africa and Americas.

“It’s like me going to your house. This is built by different spiders with different degrees of social ability. They collaborate to build these webs,” he says. It is a communal habitat, he says, and humans should learn to live like spiders do.

The artist has been testing such possibilities by creating installations of a monumental scale that allow people to experience being in a suspended web, giving birth to his Cloud Cities series. He envisions that in the future humans will be able to live in a connected way, sharing a habitat in a sustainable modular city floating above the clouds. It’s a vision of an architecture that might one day help humans cope with the effects of climate change, such as the expected reduced availability of land to live on. National boundaries will also be dissolved up in the sky—a utopia that Saraceno dreams of.

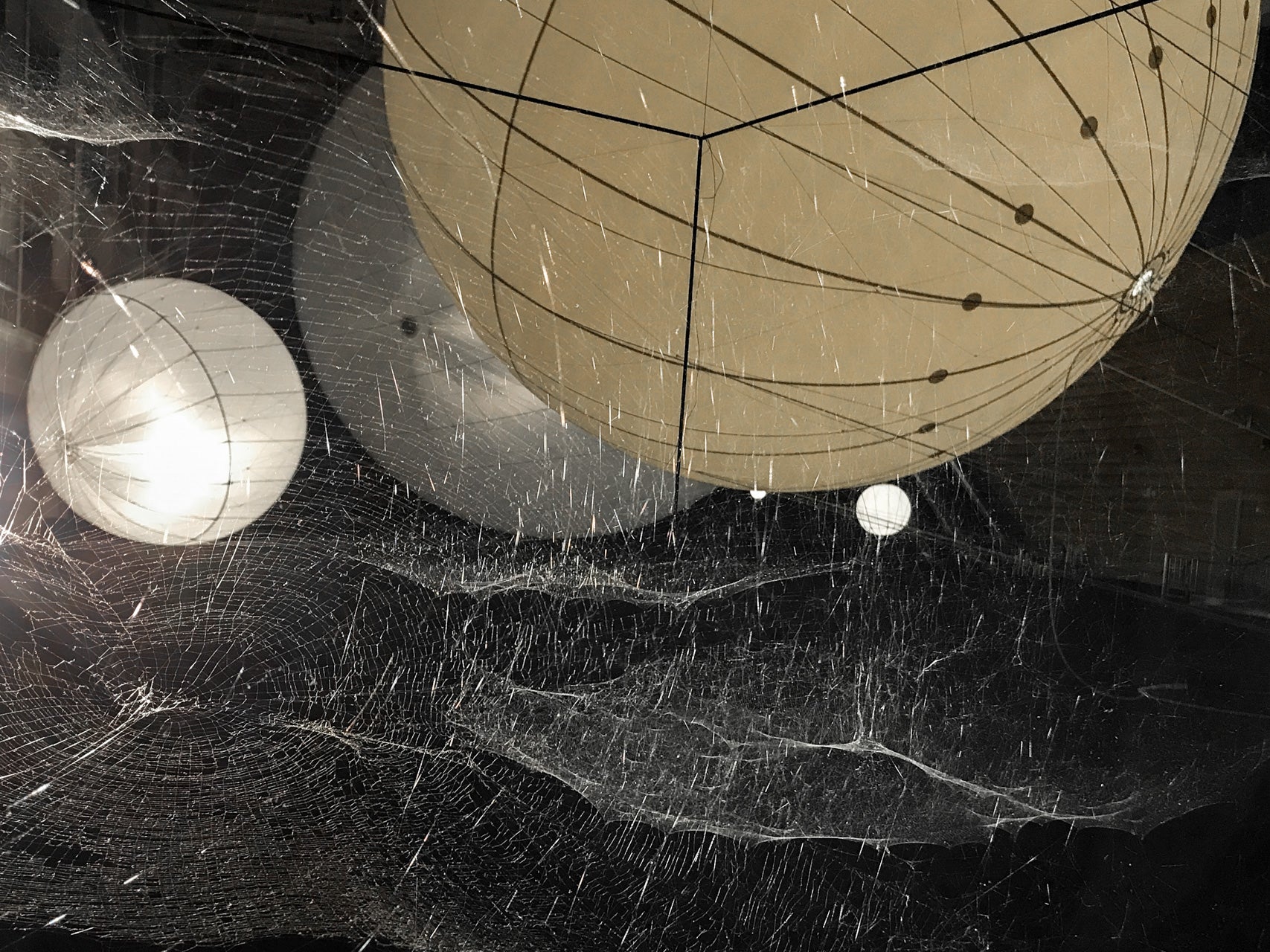

In 2012, his exhibition On the Roof: Cloud City at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York featured a large-scale sculpture made of modular compartments that visitors could climb inside. Installation In Orbit, a webbed structure containing five air-filled spheres suspended 25 meters (80 feet) above the ground is on long-term display at K21 in Dusseldorf, Germany, and people can also climb all over it, just like spiders.

Saraceno describes himself as an artist who “lives and works in and beyond the planet Earth” and apparently it’s not a joke. In addition to Cloud Cities he has created famous floating sculptures in his Aerocene series, first publicly displayed during the UN climate talks in Paris 2015 that resulted in a landmark agreement. These sculptures are propelled by sunlight—they float as the sun heats up the air that fills the sculptures—making them prototypes for how humans can travel in the future, without burning fossil fuels or consuming any other form of energy that pollutes the earth. One of these floating sculptures is also part of the show in South Korea.

“If it’s big enough it can lift a person—and even a city—up above the clouds. The sun can help us reverse gravity,” he said while launching the floating sculpture at the outdoor theater of the Asia Culture Center.

Saraceno hopes that his art can inspire a feeling of inter-connectedness that helps people accept the links between humans and everything else in the universe, including climate change. “I’m surprised to see people deny climate change, like some people in America. There’s an urgency to communicate and rebuild [the trust]. Politics isn’t dealing with the urgency of climate change,” he says.