How Hollywood manipulates you by using your childhood memories

“Nostalgia. It’s delicate, but potent. Teddy told me that in Greek, ‘nostalgia’ literally means ‘the pain from an old wound.’ It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship: It’s a time machine…It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the wheel: It’s called the carousel. It lets us travel the way a child travels—around and around and back home again, to a place where we know are loved.”

“Nostalgia. It’s delicate, but potent. Teddy told me that in Greek, ‘nostalgia’ literally means ‘the pain from an old wound.’ It’s a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone. This device isn’t a spaceship: It’s a time machine…It takes us to a place where we ache to go again. It’s not called the wheel: It’s called the carousel. It lets us travel the way a child travels—around and around and back home again, to a place where we know are loved.”

Don Draper, the smooth-talking ad executive in the TV show Mad Men, knew the economic power of nostalgia. Brands and advertisers from Kodak to Coca Cola act as its puppet masters, pulling at heartstrings and lulling us into making purchases through the promises of the past. By tapping into our emotions, nostalgia encourages us to buy a piece of a memory—a moment in time when things seemed simpler and we thought we were happier.

The exploitation of nostalgia for economic gain is perhaps most readily apparent in the entertainment industry. In 2017, there have been 34 TV spin-offs of old franchises, including new versions of Dynasty, Twin Peaks, and Heathers. Of the top 10 grossing movies for 2016, only two were new properties. The others drew from films dating back to 1894, 1938, 1959, 1977, 1991, 1997, and 2003.

George Lucas in particular is often credited for taking full advantage of nostalgia’s powers. His first blockbuster, American Graffiti, was a 1973 film that yearned for the simpler times of the 1950s and 1960s. The 1977 space western Star Wars heavily referenced the western genre, which peaked in the 1950s. Lucas has now capitalized on Star Wars’ true value, which is how it lingers in our hearts: In 2011, decades after the original film screened and in a year where no new Star Wars movie was released, over $3 billion of Star Wars toys were still sold.

In video games, Nintendo has long profited from players wanting to revisit its 1990s heyday. The Pokemon and Zelda empires have both experienced recent renaissances, with the Pokémon Go app reaching three quarters of a billion downloads and a new Zelda game driving sales of their best-selling game console, the Switch. They also released a reboot of their NES Classic console last year, which they couldn’t make fast enough to keep up with demand.

These companies tap into our emotional longing for simpler times; even Socrates yearned for the days before this new-fangled technology called “reading” ruined everything (paywall). Never content with the cards we’ve been dealt, we keep on turning old ones over, wanting to escape into their familiar embrace.

Marketers know that reminding us of positive memories also makes us buy more stuff. Experiments show that advertisements that induce more nostalgia makes viewers like the ad more, which makes them like the brand more, and therefore increases their likelihood to buy that product. When large populations begin to seek the comfort of the familiar, media creators can profit by catering to their teenage memories. It’s not that we’ve run out of fresh ideas: It’s that the old ones are safer money-making bets.

As a behavioral economist, my field attempts to simplify complicated, multifaceted social constructs like nostalgia by analyzing the general principles that underlie them. Based on my research, I’d like to argue that nostalgia’s economic prowess is caused by the interplay between two competing economic forces: depreciation and appreciation.

Depreciation of nostalgic value

One of the basic tenets of economics is the “law of diminishing marginal utility”: For most things we consume, we tire from repeated exposure. The second slice of cake is never as good as the first, and the third might give you a bellyache.

This may be an evolutionary response to balancing our need to explore our environment versus exploit it. Primitive man on the savannah had to decide whether to search for new foraging grounds on the other side of the mountain or continue using the food sources they already knew. Likewise, a typical business-school case study asks when a company should explore fresh business opportunities or continue relying on the prospects it already knows. Even if the existing options are still viable, we tend to have an inclination to seek out the new.

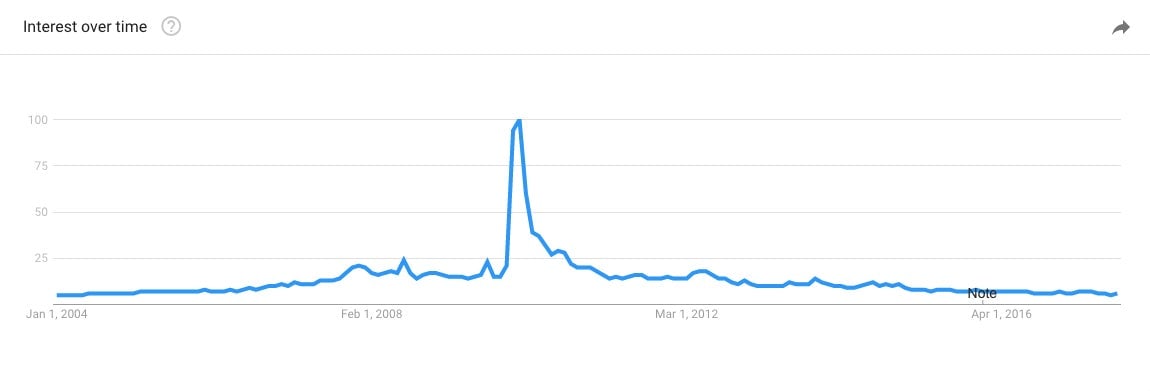

A simple example of whether an entity might be experiencing appreciation or depreciation can be seen by looking at Google search data. Economist Seth Stevens-Davidovitz argues that this data offers a uniquely honest window into the minds of internet users, revealing unexpected patterns in areas as diverse as our porn proclivities to predicting the flu and diagnosing cancer. Measuring what we are paying attention to is valuable because our attention invariably can be turned into dollars.

When you look at the Google search frequencies for the word Avatar—the name of the highest grossing movie of all time—the trend, as with most media properties, experiences a sudden spike in popularity and then a gradual exponential decay into obscurity. The further away we get from the original release the more the novelty fades, and consumers who have seen the movie once are less likely to want to see it again.

Appreciation of nostalgic value

While depreciation is common to much of what we consume, it is also counteracted by an oppositional force: properties that gain appreciation over time. While the value of some properties wither away and depreciate as they grow older, others gain value with maturity and age.

The term “appreciation” is used in finance to describe how a financial asset like a stock tends to grow in value over time as the asset gains maturity. While most physical assets depreciate with age, some appreciate, like classic cars or vintage wines. But it can be risky to bet on appreciation. For example, the potential value a bottle of wine holds increases each year the bottle matures—but with each year that passes, the chance that the bottle turns into vinegar increases, too.

Economist Joel Waldfogel also likes to use the wine term “vintage” to describe the aging of media properties, as in “Star Wars has a 1977 vintage.” The wine metaphor is apt: It can be hard to predict whether a franchise will appreciate or depreciate with time. The value of a media asset—such as a movie or video game—depends on its popularity and the passion of its fans. Like a stock, the growth of these assets is not always smooth, and can be buffeted by societal trends.

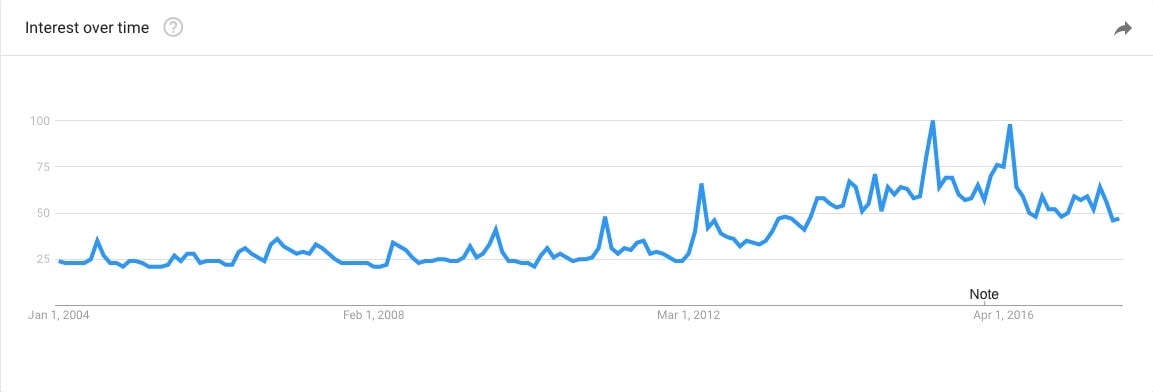

One of the biggest appreciations of the past decade has been that of comic-book franchises. Here we look at the trend of the search term Marvel, whose movies have come to dominate the top-10 lists in recent years. Most of the comics that these new movies are based off—Spider Man, X-Men, and Iron Man and The Hulk from The Avengers—were created in the 1960s. So why the sudden appreciation now?

Nostalgia as an economic force

Neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky argues that our preferences for music (and other media) is formed in our teenage years and early twenties, when our brain is most primed to explore new things. For example, Spotify recently launched a time capsule playlist that features songs from when the listener was a teenager, and it quickly became one of their most popular features. This was likely because music and movies that trigger memories of our carefree younger years normally put us in a good mood and increase our likelihood to buy related products. Content creators know this and attempt to create value by triggering the happiest memories of those they target.

Marvel fans who were teenagers during the comics’ heyday are at the peak of their spending power today; their nostalgia for their younger years is helping drive ticket sales. But Marvel is also taking advantage of some compounding interest: today’s teenagers who are experiencing the franchise as something new and novel. Marvel’s comic-book business as measured by share price peaked in 1993 and then crashed just three years later, meaning that most millennials and Gen Z kids were either born or came of age too late to experience the hype the first time around. After the near-demise of Marvel, the modern movies are their first exposure of these properties, which creates a second demographic to drive the films’ success.

This is then compounded yet again by another component psychologists identify with nostalgia: its ability to induce feelings of social connectedness. The economic study of conformity concerns itself with how our consumption choices depend on our connections to other people. Memories acquire meaning not just in the connections made in our own mind, but in the connections of the collective consciousness. In work published by the Marketing Science Institute, my co-authors and I show how our consumption choices—such as TV shows and sneaker brands—acquire meaning based on how others in society decide what to consume. For example, watching Game of Thrones acquires an additional extrinsic value when we start talking about it around the water cooler.

This gives Marvel and other franchises from the late 1970s to the early 1990s—such as Star Wars (1977), Blade Runner (1982), and Jurassic Park (1993)—the perfect trifecta of economic forces to attract our entertainment dollars:

- Franchises that are 20 to 40 years old appeal to the nostalgic memories of those aged 35-55, which is the demographic where earnings and spending power begin to peak.

- Franchises from that era are also just old enough for younger generations to view them as novel media properties anew, thus circumventing depreciation.

- This ability to appeal to two different generations is amplified by our social connectedness, which reinforces the whole package.

And there’s arguably a fourth factor that will see this cycle repeat in decades to come: Fast forward another 20 to 40 years, and the millennials who are discovering Iron Man for the first time might feel nostalgic for the remakes (of the remakes), and the cycle begins anew.

So for those who complain that “nothing is new anymore,” we have no one to blame for these constant franchise reboots but ourselves. Firms supply the nostalgia that consumers are seeking, but there is a way to game the system: We need to become more aware of how sellers manipulate our memories to peddle their wares. As recent Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler has promoted, a better awareness of the social forces that drive economic behavior could help us all demand better media choices, which could in turn drive media producers to improve their offerings.

As for the next reboot that takes advantage of the holy trifecta? I have my bets on Titanic: 2020.

Read more of the Quartz Ideas series on The Nostalgia Economy.