Cell phones are stepping in where governments are failing

Myanmar is opening up politically, and among the first, largest civil society campaigns is a social movement organized over Facebook for cheaper cell phone calling plans. Syria has been locked in civil war for almost two years; despite the strife—or because of it—cell phone subscriptions have taken off. In Nairobi’s largest slum, a local initiative to digitally map the muddy streets, open sewers, and infrastructure needs has bloomed into a network of community groups that deliberate over development priorities and then collect taxes to spend on those priorities.

Myanmar is opening up politically, and among the first, largest civil society campaigns is a social movement organized over Facebook for cheaper cell phone calling plans. Syria has been locked in civil war for almost two years; despite the strife—or because of it—cell phone subscriptions have taken off. In Nairobi’s largest slum, a local initiative to digitally map the muddy streets, open sewers, and infrastructure needs has bloomed into a network of community groups that deliberate over development priorities and then collect taxes to spend on those priorities.

Wherever governments are in crisis, in transition, or in absentia, people are using digital media to try to improve their condition, to build new organizations, and to craft new institutional arrangements. Technology is, in a way, enabling new kinds of states.

It is out of vogue in Washington to refer to failed states. But regardless of the term, there are an unfortunate number of places where governments have ceased to function, creating openings for these new institutional arrangements to flourish. Indeed, state failure doesn’t always take the form of a catastrophic and complete collapse in government. States can fail at particular moments, such as during a natural disaster or an election. States can also fail in particular domains, such as in tax collection.

Information technologies like cell phones and the internet are generating small acts of self-governance in a wide range of domains and in surprising places.

Sometimes even governments-in-exile find cohesion online. Libya’s transitional government formed online a month before most leaders were able to even get on the ground. Syria’s government-in-waiting started haggling online as soon as protesters took to the streets in Damascus. There are no clear examples of states that have been totally “born digital,” but there are many examples of people using digital media to provide governance.

Almost everyone can connect to almost everyone else these days—cell phone penetration in most countries is upwards of 80%. So when the modern state fails in one or more ways, people go online, check in with family and friends, and make new plans.

Most of the world gets its news from various forms of state-run news agencies. But citizen journalists pop up whenever the state-run media is so corrupt that it can’t provide a reasonable public service. Indeed, before the Arab Spring, the best investigative journalism in Tunisia and Egypt was only found online, and those exposés on corruption and abuse did much to undermine the regime. Even China’s ruling Communist Party has trouble controlling its bloggers and Weibo users, especially on topics like corruption and pollution. When street shootouts between warring Mexican drug cartels made cities like Monterrey inhospitable, citizens developed their own emergency notification networks with Twitter. Urban governments failed to provide public warning systems, so citizens created their own public communication system over digital media.

Almost every country in the world now has a digitally-enabled election monitoring initiative of some kind. Such initiatives are rarely able to cover an entire country in a systematic way, and they often need the backing of funding and skills from neutral outsiders like the NDI. But even the most humble projects to map voting irregularities, video the voting process, or crowd source the poll station results helped expose and document electoral fraud.

***

There is lots of technology at work in places we don’t usually look. But is it really providing governance? It is not so much that the smartphones have taken over government, but that people are using information technology to do quick institutional repairs.

Just because a development project uses social media in some way doesn’t guarantee good governance. But when states fail to deliver governance goods, communities increasingly will step up, digitally. This shouldn’t be surprising, given how much excitement there is around the prospect that e-government will significantly improve the capacity of even rich governments to deliver services. However, what we’re talking about here is about more than service delivery: it is about the capacity of communities to set rules, stick to them, and sanction the people who break the rules. A sovereign state is one that can implement and enforce policies. When states don’t have these capacities, a growing number of communities use digital media to not only provide services, but to do so in a way that amounts to the implementation and enforcement of new policies.

Digital media can strengthen social cohesion to such a degree that when regular government structures break down, strong social ties can substitute. In other words, if the state is strong but the society weak, information technologies can do a lot to facilitate new forms of governance.

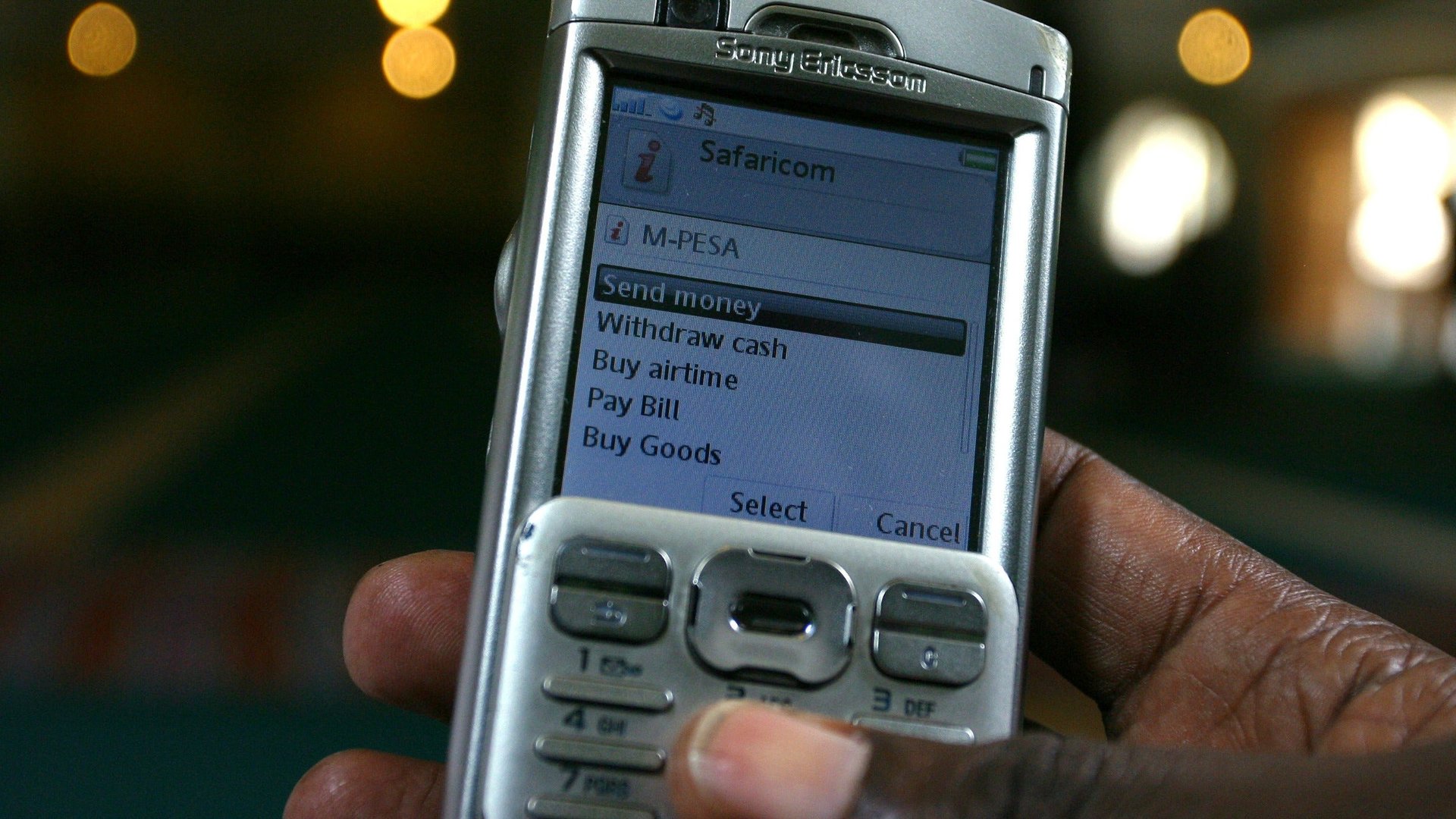

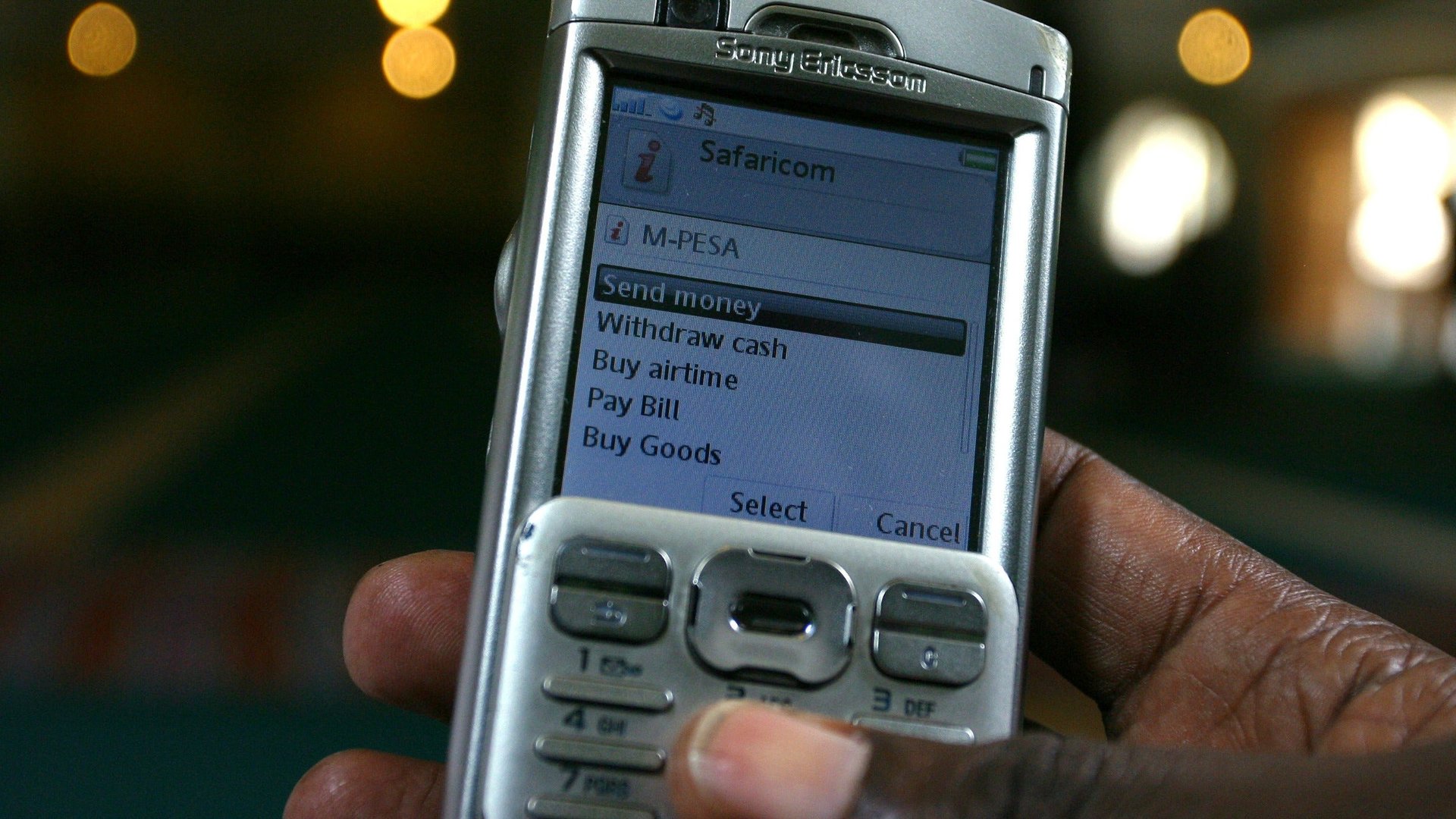

The real innovations in technology-enabled governance goods are in the domains of finance and health. In much of Sub-Saharan Africa, banking institutions have failed to provide financial security or the benefits of organized banking to the poor. This stems from a lack of interest in serving the poor as a customer base, but also from a regulatory failure on the part of governments. These days, wherever financial institutions have failed whole communities, cell phones support complex networks of private lending and community banking initiatives.

M-Pesa is a money transfer system that relies on cell phones, not banks or the government. Airtime provides an alternative currency to government-backed paper. Since a banking sector that gets some regulatory oversight is missing, people have taken to using their phones to collect and transfer value. In the first half of 2012, M-Pesa moved some $8.6 billion, so this isn’t chump change.

Moreover, people make personal sacrifices to be able to have the technology to participate in this new institutional arrangement. iHUB research found that people would forgo meat at mealtime if it would save enough funds to allow them to make a call or send a text message that might eventually result in some economic return. A typical day laborer in Kenya might earn a dollar a day, but the value of personal sacrifices for cell phone access amounts to 84 cents a week. Two-thirds of Kenyans now send money over the phone. The service is popular precisely because financial institutions are too corrupt or not interested in serving the poor.

An important part of any government has always been infrastructural control, and maps have historically been the index to how infrastructure is organized and therefore a key artifact of political power. Civic leaders in one of Nairobi’s uncharted slums decided to make their own digital map specifically for the purpose of identifying public infrastructure needs and raising their own taxes to help pay for the most urgently needed repairs. Ushahidi, the online mapping platform, has claimed many important victories in the battle to provide open records about the demand and supply of social services. In doing so, they’ve taught the United Nations a few things about managing disaster relief, and they’ve schooled the Russians about coordinating municipalities to deal with forest fires and lost children.

FrontlineSMS, another cell phone enabled governance mechanism, helps improve dental health in The Gambia, organize community cleanups in Indonesia, and disseminate recommendations about reproductive health in Nicaragua.

Of course, this type of tech-based governance isn’t always a positive thing, and it can sometimes result in vigilantism. In many parts of the Philippines, the government is unable to dispense justice in a consistent way, and can’t always follow through in punishing those convicted of serious crimes. So vigilante groups equipped with cell phones and social networking applications have organized themselves with their own internal governance structure to dispense justice. Over SMS they deliberate about targets, negotiate over punishments, and delegate tasks. Such groups are responsible for upwards of 10,000 murders in Manila, and they are blamed for killing both drug lords and journalists on Mindanao.

Plus, plenty of these technology-enabled governance systems are stillborn without some kind of state backing. Most of the Congo is un-policed, and the government cannot track the movement of local militias. In the absence of the institutions, the Voix de Kivus network documents sexual assaults, reports on the kidnapping of child soldiers, and monitors local conflicts. UNOCHA, local NGOs, philanthropists, and USAID study the reports. In this case, the organizers admit that there is little evidence of a governance system taking root. Reports of conflict are now credibly sourced and appear in real-time, but nobody acts on the knowledge. In order to have serious impact, most social media projects need to work in concert with government.

Most examples of technology-enabled governance systems come from the parts of the world where the state really has failed to govern. But even in the U.S., digital media provides the work-around to weak government performance. Average Americans who felt the U.S. was not doing enough to support the Green Movement in Iran in 2009 could dedicate their own computational resources to democracy activists by hosting a TOR server. Citizens unhappy with government efforts at overseas development assistance turn to Kickstarter.com to advance their own aid priorities. The next cyber-battle might be started by Bulgarian hackers or Iranian Basijis, but it might also be started by Westerners using basic online tools to launch their own Twitter bots.

These may seem like isolated examples, but the reason such initiatives are important is that they are contagious. In the last 10 years, we’ve gone from imagining that the Internet might one day change the nature of governance to finding a plethora of examples of how this is really done. Cell phone companies across Africa, Latin America and Asia now offer asset transfer systems, many of which are structured like M-Pesa. There are some 35,000 Ushahidi maps in 30 languages. In complex humanitarian disasters, most governments and United Nations agencies now know they need to take public crisis mapping seriously.

International aid can help prop up a failing state and can help fund rebuilding operations in a state that has failed. However, the citizens themselves have to do the hard work of the actual rebuilding. These days, as people see their state falling apart, they pull out their cell phones and make their own arrangements.

Philip N. Howard is a professor at the University of Washington and the School of Public Policy at the Central European University.