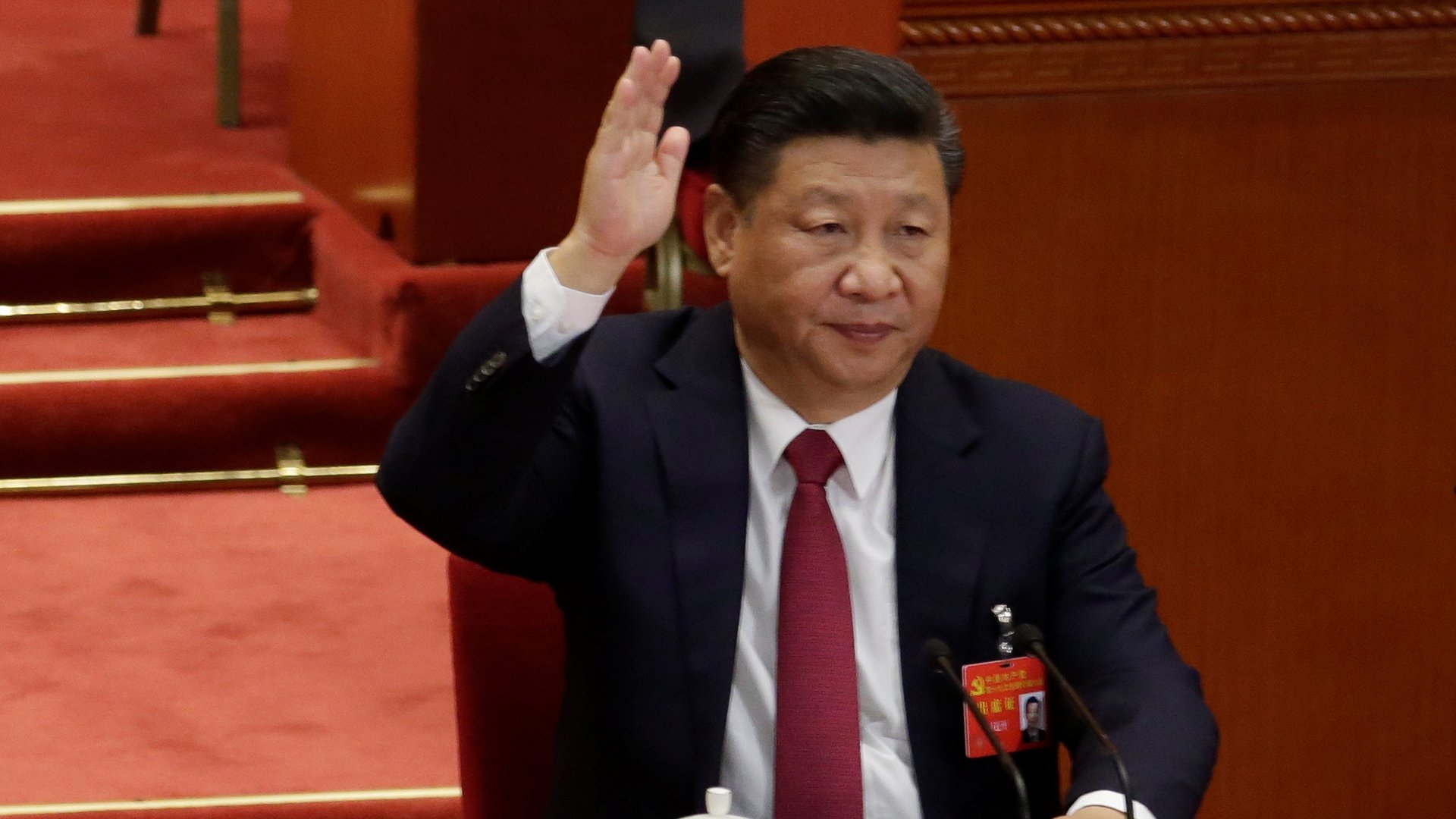

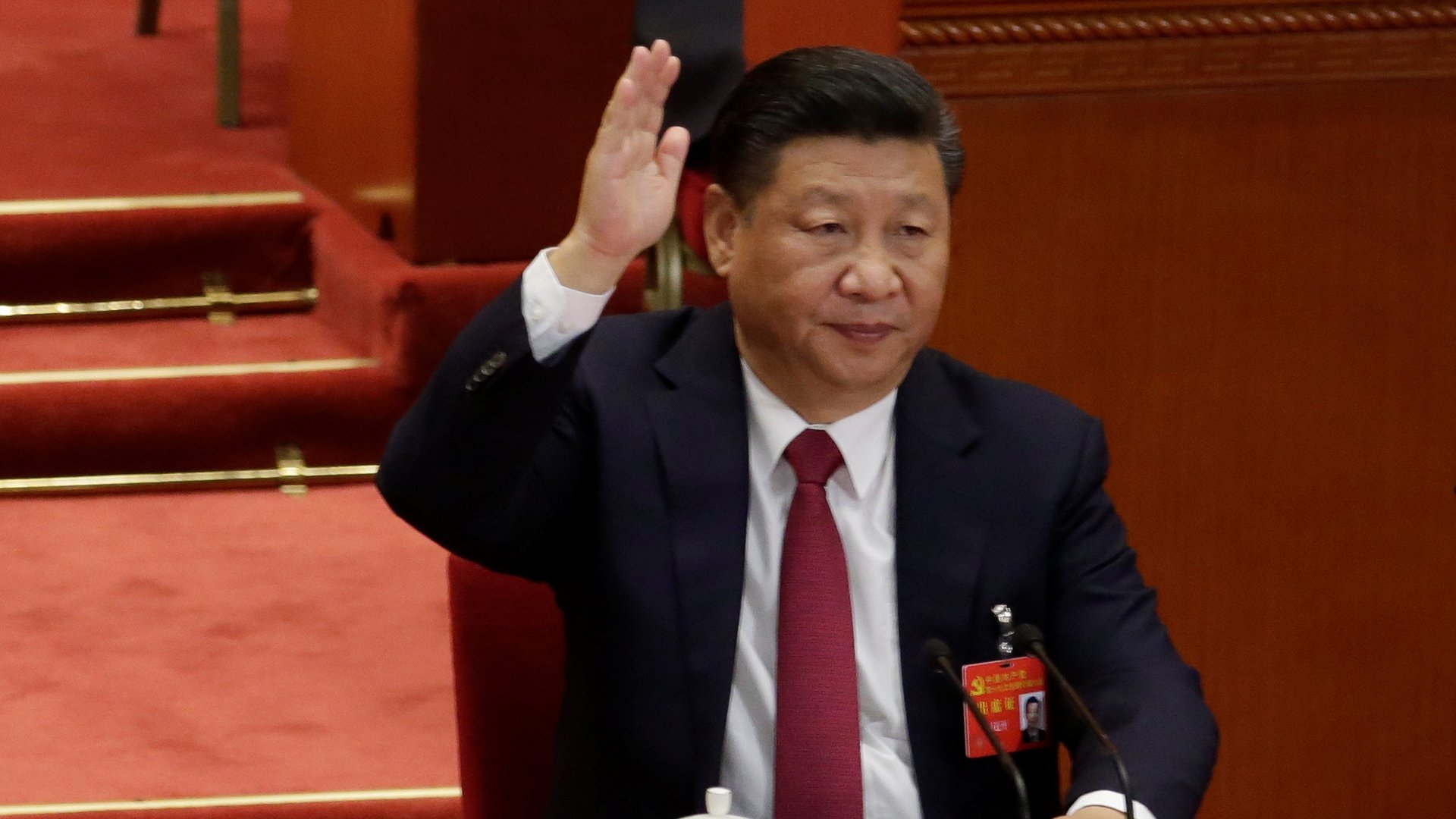

China’s Xi Jinping just put himself on par with Mao

Chinese president Xi Jinping emerged from a pivotal Communist Party meeting on Tuesday on par with Mao Zedong, the autocratic leader who founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Chinese president Xi Jinping emerged from a pivotal Communist Party meeting on Tuesday on par with Mao Zedong, the autocratic leader who founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

The 19th National Congress, a major leadership reshuffle event, wrapped up Oct. 24 with an amendment to the party’s constitution that saw Xi’s name added to the document (link in Chinese) along with a signature policy that will guide the party in the years to come.

Recent Communist leaders have seen their theories added to the constitution—but not their names. Until today, only Mao and Deng Xiaoping, who opened up China’s economy during the 1980s, enjoyed that honor. The addition of the phrase—“Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”—elevates the already enormously powerful Xi to the same status as the country’s most revered leaders.

Xi first put forward the term without attaching his name to it on Oct. 18, when he opened the leadership meeting with a three-hour speech. It’s a broad concept that he explained in 14 parts that covered everything from party discipline to economic reform to national security. The new era appears to refer to China’s next challenge, now that extreme poverty is rare, to help the country become a higher-income one. In his remarks last week, Xi declared that “the principal contradiction” facing China’s socialist society has evolved. In the past, the contradiction was between “the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people and backward social production.” Now, it is between “unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life,” Xi said.

Every top Chinese leader has his own signature political theory that is enshrined in the party constitution as a way to sum up his legacy. These terms, however, are evidently not equal in stature. For Mao, it’s “Mao Zedong Thought.” For Deng, it’s “Deng Xiaoping Theory.” And for Xi’s two immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, it was “Three Represents” and “Scientific View of Development.”

Mao Zedong Thought first appeared in the Communist Party’s constitution during its seventh national congress in 1945. The term disappeared from the document in the eighth congress in 1956—the first congress held after the founding of the People’s Republic—as the party was concerned about developing a cult of personality similar to that of the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. The term made a comeback during the ninth congress in 1969, in the midst of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a chaotic campaign that mobilized the masses to purge disloyal officials. It’s seen as referring to the localizing of Marxism, through Mao’s emphasis on China’s rural peasantry as the heart of the country’s revolutionary zeal.

During the 15th congress in 1997, Deng Xiaoping Theory was written into the party constitution months after Deng had passed away. That enshrined Deng’s focus on economic development, and his philosophy that it was perfectly possible to adapt elements of a market economy with socialism in China.

The theories of Jiang and Hu were added to the party constitution at the end of their tenures as party general secretary, in 2002 and 2012, respectively.

Xi Jinping has only served one term as party general secretary, and is now beginning a second. In that respect, having his name in the constitution while he is still in power, raises Xi to an even higher status than Deng.

It also vindicates dozens of tea-leaf readers, who had been predicting this move. Confidence in the likelihood of it happening rose as dozens of senior party officials from the central leadership, provincial level and the military made explicit references to a tweaked version of the phrase, adding Xi’s name, during discussions on the sidelines of the congress. These included six of the seven current members of the Politburo Standing Committee—the apex of the party’s leadership—apart from Xi.

The grand finale of the congress actually comes Wednesday, when Xi will complete the leadership transition by leading the newly selected Standing Committee members to meet the press. The New York Times (paywall) and the South China Morning Post have reported the same set of names, a lineup that has no people young enough to be Xi’s successor as party chief in 2022. If correct, that is a further signal that Xi could break with convention to hang on to power beyond his second term.

But a separate development showed that Xi honored another convention—the unwritten rule of retirement at age 68. The absence of 69-year-old Wang Qishan in the new 200-strong Central Committee (link in Chinese) unveiled Tuesday means that he will be stepping down from the apex group. Speculation had been rife that Wang, a trusted ally of Xi, could stay in his post as the party’s top graft buster for five more years, which would have been seen as the strongest indicator yet that Xi himself would break with tradition in 2022, when he will be 69, and serve another term.