The Niger ambush highlights the precarious nature of US military engagement in Africa

Three weeks after eight US and Nigerien soldiers died in an ambush in Niger, officials are still struggling to put together details of what actually happened.

Three weeks after eight US and Nigerien soldiers died in an ambush in Niger, officials are still struggling to put together details of what actually happened.

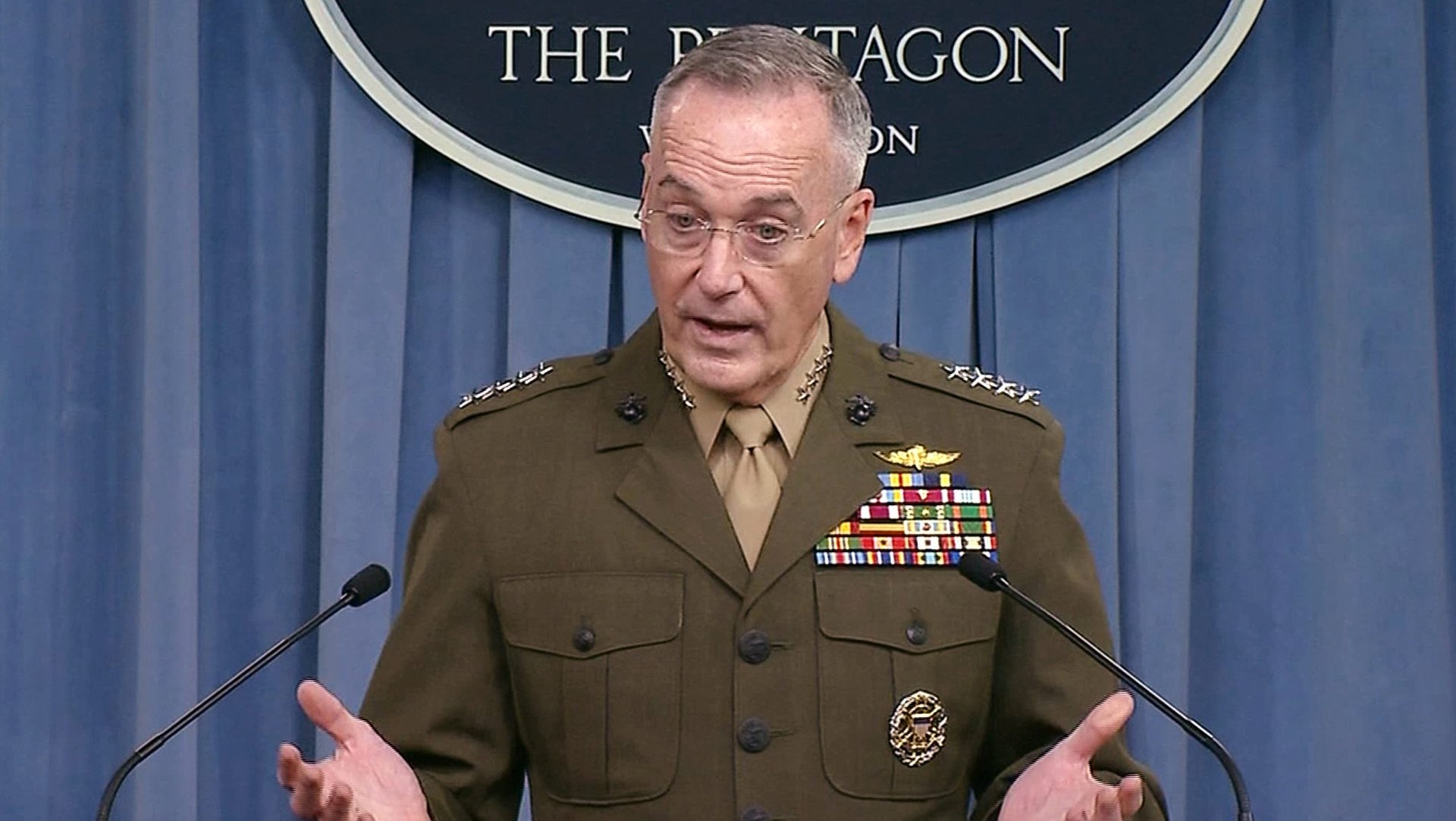

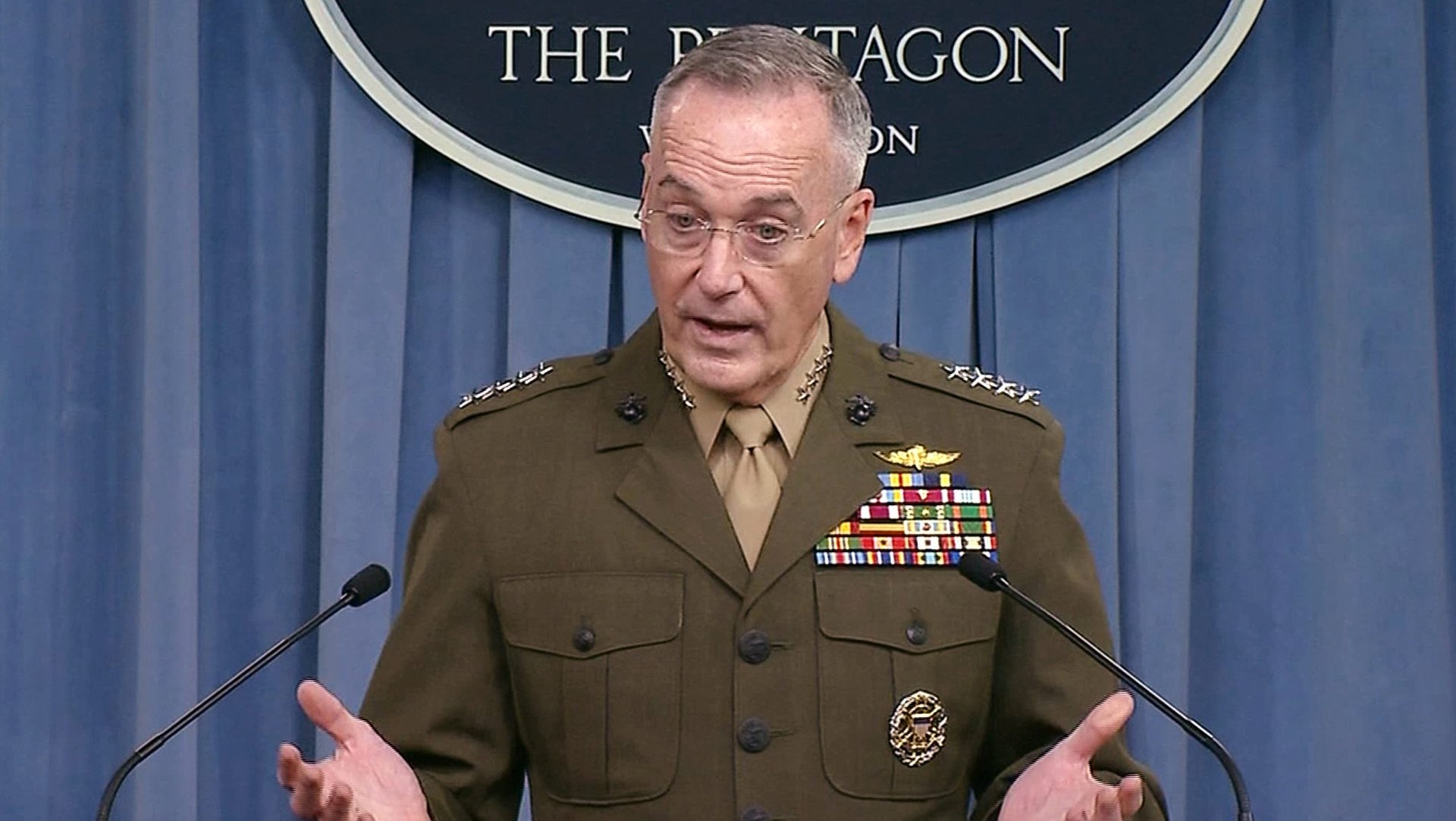

On Monday (Oct. 24), the top US general Joseph Dunford said key questions about the operation remained unanswered. These included whether the troops had adequate intelligence and equipment, why it took them an hour to call for help, hours before those injured and killed were evacuated, and days before the body of sergeant La David T. Johnson, a mechanic serving with the unit, was recovered. The investigation is also compounded by the conflicting narratives and media reports that have emerged since the attack took place.

On Oct. 3, a dozen American troops and about 30 of their Nigerien counterparts departed for an area around 85 kilometers (53 miles) north of the capital Niamey. On returning the next day, they were attacked by dozens of militants on vehicles and motorbikes, leading to the death of four American soldiers, four Nigeriens, and the wounding of eight others from both sides. French warplanes arrived an hour later for air support and helped transport the bodies of the dead soldiers from the battlefield.

In recounting the event, Dunford speculated that the troops thought they could defend themselves against the militants who attacked them, but added: “I don’t know how this attack unfolded. I don’t know what their initial assessment was of what they were confronted with.”

The event has brought into sharp focus the precarious nature of the US military involvement in Africa. The ambush and its outcome also show the limits of American power in a country and region where the US is expanding its presence and counterterrorism efforts. The US Africa Command (AFRICOM) has 800 military personnel stationed in Niger, running a drone operation, and supporting the government in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance efforts. And as the threat of terrorism looms over the entire Sahel region, Niger has become an indispensable Western ally, closely working with the over 3,500 French troops based in the region.

Yet for an administration that has had a hands-off approach towards Africa, the attacks present an avenue for due criticism. It took president Donald Trump 12 days to speak about the ambush, with senator John McCain saying he was ready to subpoena the government to get more information. A Florida congresswoman even called the attack “Trump’s Benghazi,” in reference to the coordinated attack on the US embassy in Libya in 2012 that killed ambassador Christopher Stevens.

The Niger operation also underscores the massive shadow wars the US is undertaking in Africa, and the bleak reality that surfaces when these operations go awry. For instance, a US airstrike in Somalia killed government soldiers in 2016, and in August, Somali forces supported by US troops killed civilians in a village near the capital Mogadishu. In Niger, French officials were reportedly frustrated with the American troops for going to the field with limited intelligence and without a contingency plan.

Even as they assist African governments to tackle Islamic extremism, observers say the long-term effect of these operations could be short-lived and unsustainable. In the wake of the recent attack, defense secretary Jim Mattis said the military was shifting its counterterrorism strategy to focus more on Africa, with a view to increasing lethal force against terrorists.

William Assanvo, the west Africa regional coordinator with the Institute for Security Studies, says that such a move, “if not properly thought and carried out may further contribute to an escalation of the situation on the ground.” And if the new rules of engagement lead to civilian casualties, “this may alienate local population and provide extremist groups with more recruits.”