One historic meeting determined the size and shape of every passport in the world today

On Oct. 21, 1920, the League of Nations convened in France for a meeting that would shape modern travel.

On Oct. 21, 1920, the League of Nations convened in France for a meeting that would shape modern travel.

After World War I, easing border crossings by train was a priority, but the lack of a standardized passport design posed “a serious obstacle to the resumption of normal intercourse and to the economic recovery of the world,” the League noted. Border officials struggled to scrutinize foreign certifications of dizzying shapes and sizes, with sometimes partial information and little guidance as to what was authentic.

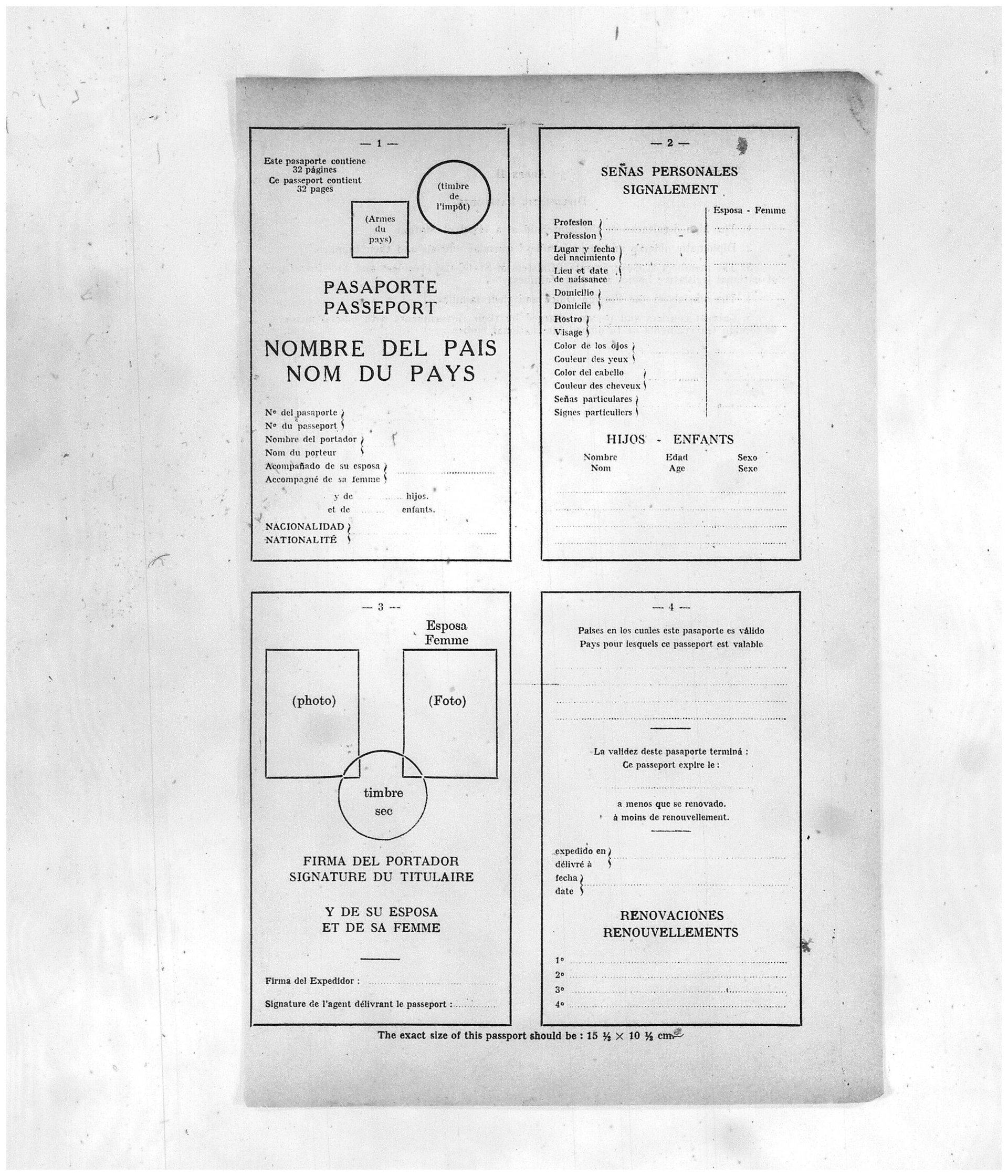

The Paris Conference on Passports & Customs Formalities and Through Tickets specified the size, layout, and design of travel documents for 42 nations. It ratified the template for a 32-page booklet exactly 15.5 cm x 10.5 cm (6.1 inches x 4.1 inches) with the first four pages detailing the bearer’s facial characteristics, occupation, and residence.

Assuming that travelers were married males traveling with their families, the layout included a box for a photo of the bearer’s spouse and space for the names of his children. Each passport was to be in French and at least one other language; its cardboard cover would have the country’s name and coat of arms centered on it; and the document should cost no more than 10 francs.

Although now governed by standards set by the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organization, passport layouts have remained much the same for nearly 100 years. But the invisible technology that secures them has greatly advanced, including layers of watermarks, holograms, disappearing inks, perforated numbers, fluorescent threads, embossed letters, see-through registers, and book-binding techniques.

Most notably, a small rectangular icon on the cover () denotes the presence of a microchip containing the bearer’s biometric data. Now widespread, the ePassport was pioneered by the Malaysian government, which has been using microchips invented by a Kuala Lumpur-based biometric company, IRIS Corporation, since 1998.

However, the passport booklet itself may soon become obsolete. Australia is already testing a face-scanning-based system called “Seamless Traveller” that will eliminate the need for most travelers to show passports at borders by 2020.

Like the League of Nations passport committee a century ago, officials hope the system will ease queues and “transform the border experience” for travelers. But the small magic of having a nostalgic, pocket-sized record of one’s travels will be lost.

This piece is featured in Quartz’s new book The Objects that Power the Global Economy.