There’s at least one place in Africa where China’s “win win” diplomacy is failing

Juba, South Sudan

Juba, South Sudan

The rice giving ceremony is more than an hour late. Zhang Yi, China’s economic attaché in South Sudan, sits in the mid-morning heat in a full suit, occasionally checking his phone, a mobile headpiece clipped to his ear. Next to him, a dozen South Sudanese bureaucrats and journalists are waiting in plastic chairs under a pair of trees. Trucks meant to transport 1,500 tonnes of rice donated by Beijing to three states in the country’s northeast and west haven’t arrived yet.

After a few more minutes, Zhang signals that the ceremony should go ahead. He reads off a list of China’s recent donations to South Sudan: a total of 8,800 tonnes of rice and 27 containers of blankets, mosquito nets, tents, and other supplies. Afterwards, the group doesn’t quite know what to do. Zhang suggests a photo. He and his South Sudanese counterparts pose with the donated bags of rice, labeled in bold red print: CHINA AID.

It’s a rare scene. China isn’t typically known for its humanitarian aid in South Sudan, where a civil war has displaced a third of the population and left almost half the population at risk of starvation. Tens of thousands of South Sudanese have died in the fighting; there is no formal death toll.

Instead, China is seen as an investor. The state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), one of the largest oil companies in the world, controls around 40% of the two main oil consortia in the country. Other large Chinese companies have set up shop, waiting to build roads, buildings, and other infrastructure. Chinese entrepreneurs run restaurants, private hospitals, factories, and furniture stores. Last year, China’s former special representative on African affairs, Zhong Jianhua called South Sudan a “paradise for investors.”

Elsewhere on the continent, China is also seen primarily as a business partner. It’s a foreign policy based on what Chinese leaders are fond of calling ”mutually beneficial” or “win-win” cooperation. Chinese companies get lucrative contracts and experience overseas while the host country receives needed infrastructure, jobs, and eventually technology and skills.

“When we are inviting foreign investors it’s not a lose-win, it’s a win win,” says Zhang. “They are bringing expertise. They are training the local population and eventually they will transfer knowledge of management and skills, and practical technology.”

But so far, no one appears to be winning. And South Sudan may be the starkest example yet of when China’s so-called win-win diplomacy doesn’t work. A civil war that has lasted almost four years has put infrastructure projects, loans and other financial help from Beijing on hold. Many private Chinese businesses and investors have left over the past year as the prospect of peace appears more remote. Chinese oil giant CNPC was losing as much as $2 million a day when oil prices dipped below $30 a barrel last year.

Researchers and observers have taken to calling South Sudan a testing ground for China’s ascendent role as a global power. Chinese officials themselves have referred to South Sudan as a “pilot case for Chinese diplomacy.” The experiment hasn’t gone so well.

“South Sudan represents China’s first engagement with crisis diplomacy as a modern rising global power. But far too much attention has been paid to the novelty of this event, in neglect of China’s lackluster results,” says Luke Patey, author of The New Kings of Crude, a book on China’s oil interests in the Sudans.

China has stepped up humanitarian aid like rice donations, but as the situation in South Sudan grows more desperate this isn’t enough. ”We have millions of people in Uganda, in POCs. We need somebody to help with food, with water,” says Leben Nelson Moro, who teaches at the University of Juba’s Center of Peace and Development, referring to the United Nations protection of civilian (POC) camps for IDPs within the country.

“China will tell you, ‘We are here for business. We gain; you gain,’” he says. “That is good in normal times but for South Sudan, this is out of place.”

On hold

China’s involvement in South Sudan has always been about business. CNPC began developing Sudan’s oil fields in the 1990s, in what was one of China’s first major overseas investments. After years of fighting between the north and the south, a peace deal in 2005 paved the way for South Sudan’s independence.

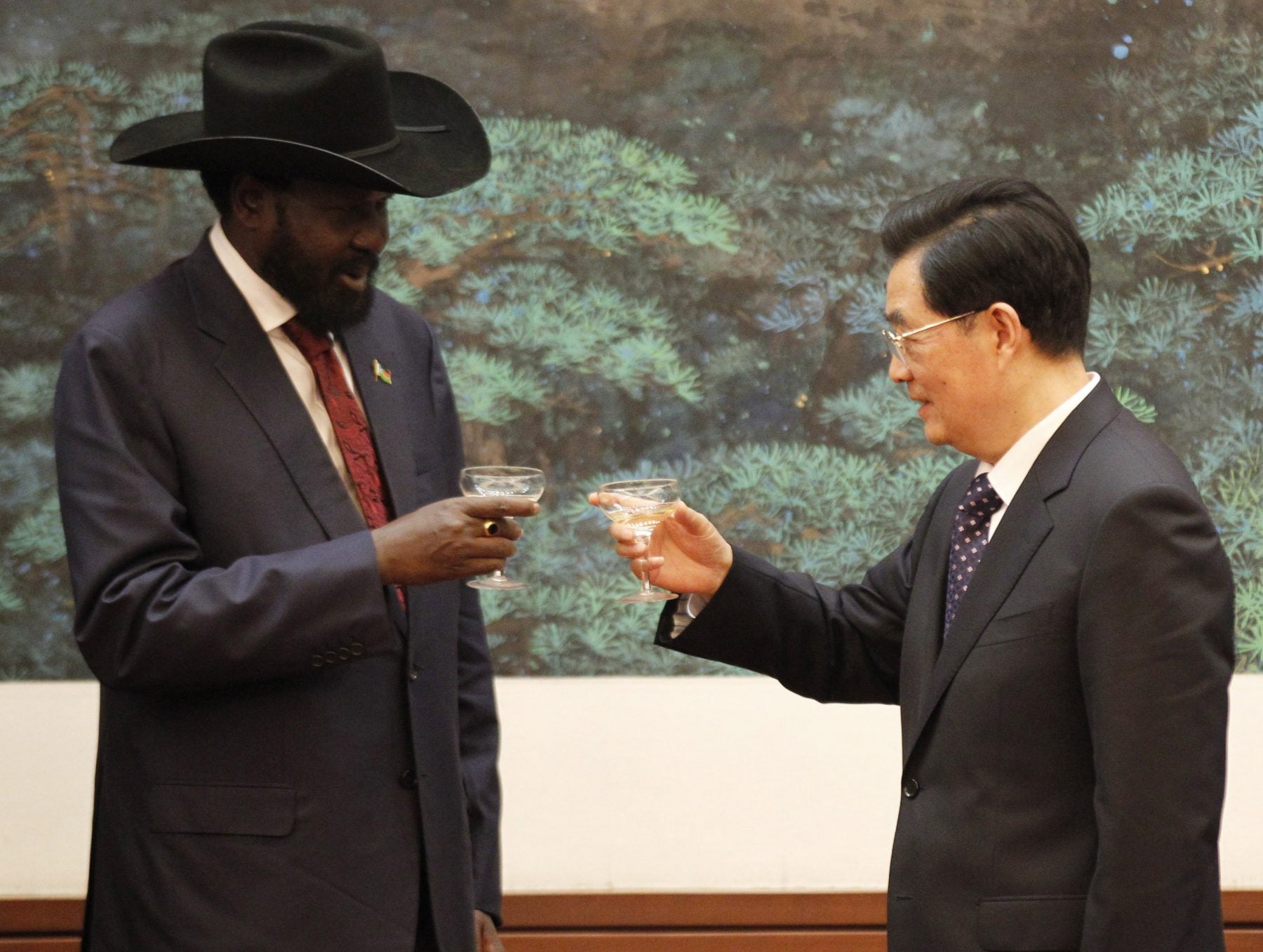

Despite years of support for Khartoum in the north, China moved quickly to establish ties with the future government of South Sudan where 75% of the oil reserves would be found. On July 9, 2011, when South Sudan became the world’s youngest nation, China was among the first countries to recognize Juba.

Chinese companies, entrepreneurs, and small business owners soon descended on the new country, anticipating a rush of infrastructure projects, a flood of Chinese financing, and few competitors, Western or otherwise. In 2012, there were as many as 10,000 Chinese nationals working in the country and more than 100 Chinese companies registered, most of them private firms.

They opened water bottling plants, restaurants, super markets, restaurants, and hotels. A handful of Chinese restaurants served only Chinese patrons. The flights into Juba were always full of Chinese passengers, local Chinese expatriates remember.

“The country was a blank slate. You felt like whatever you did, as long as you did it well, the returns would be good,” says Dai Binggang, the owner of a Sichuanese restaurant, who came to Juba in 2012 from Uganda where he was working for a Chinese construction company. His restaurant, a single dining room under a thatched roof, is next to a Chinese-run hotel, and an office for a South Sudan-China friendship association.

But six years after independence, the world’s newest country is still struggling to find its footing. Fighting in 2013 between government forces under president Silva Kiir and those loyal to his rival and former vice president Reik Machar turned into a many-sided civil war that engulfed much of the country.

A peace deal, mediated with Chinese help, between president Kiir’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) government in Juba and Machar, head of the SPLA in opposition, fell apart last July. The two sides fought in Juba, killing hundreds of civilians over the course of four days.

Today, the only major Chinese-funded infrastructure going ahead is a renovation of the runway, navigation system, and parking lots of Juba International Airport, a contract worth about $160 million. South Sudan, a country the size of France, has only around 200 kilometers of paved road.

“Economically South Sudan has not benefitted a lot from China,” says a South Sudanese diplomat who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to media. “We are talking about roads, schools, hospitals, agriculture, and power—these are the most important for the development for our country. China has not done much except for the airport.”

That’s in large part because the flood of Chinese money has yet to arrive. South Sudanese officials excitedly announced an $8 billion Chinese loan in 2012 that never materialized. The Chinese embassy says that figure was “just a wish,” a request by South Sudan for a long list of projects ranging from a community for retired soldiers to a hydropower plant, and a 1,600-kilometer road through western and central South Sudan. Chinese banks committed to a few of the projects, but they have been put on hold.

“Without a peaceful environment, there’s no such force to protect those operations. It is not a good situation for these big projects for the time being,” Zhang says, speaking on behalf of the Chinese embassy. Other countries are not having more luck, he notes. A bridge, funded by Japan’s aid agency, connecting Juba to a critical highway leading to Uganda, has also been halted indefinitely.

While Chinese companies are known for having a higher risk tolerance, South Sudan has proven too volatile. Large state-owned or private Chinese companies have evacuated most of their staff, leaving only a skeleton crew. Those running smaller businesses have also left, frustrated by the plummeting South Sudanese pound (SSP). Government workers and military in Juba haven’t been paid their full salaries for most of the last half year, hurting the spending power of some of these businesses’ main clientele.

The Chinese embassy says that of about 140 Chinese businesses in South Sudan only half are still active. As few as 500 Chinese expatriates remain in the country. Many of those who have stayed are just trying to recuperate their investments before leaving.

Dai curses while he prepares a plastic bag full of South Sudanese pounds to buy diesel off the black market for the generator to run his restaurant—20,000 South Sudanese pounds for 140 liters of oil. His business partner is watching a Chinese soap opera in the empty restaurant. “We’ve invested all of our money here. If we just leave it, we won’t have anything,” he says.

China Aid

China is working to make its humanitarian contributions more visible. At Juba Teaching Hospital, corrugated metal walls outline what will be a new maternity ward and an outpatient and emergency center. They bear the same “China Aid” label as the bags of rice Zhang donated. A new building for the foreign ministry, visible over its walled enclosure, is also clearly marked with the same logo. Even more noticeable are the 2,600 Chinese peacekeepers who help man a UN POC camp for displaced South Sudanese.

At the urging of the Chinese embassy, Chinese companies are also trying to do more. CNPC cleared and leveled the site for another UN civilian protection camp. The company has built hospitals and schools in the oil fields where it operates, according to the embassy, as well as a computer lab to Juba University. Every year, China sponsors hundreds of South Sudanese government officials, business people, and students, to attend training or schooling in China.

In place of more economic cooperation, China has stepped up its aid in South Sudan, a contrast to its traditional approach to international development. Most of the funds China provides developing countries are commercial loans and other forms of overseas financing that don’t fit the OECD’s definition of official development assistance, which maintains that money given can’t profit the donor country, among other conditions.

“China has always wanted to be a development partner, not a donor in South Sudan, but now China has little choice but to pull back on these initiatives,” says Daniel Large, an associate professor at the School of Public Policy at Central European University, who has researched China-South Sudan ties.

The results of these efforts have been mixed. When fighting between government and rebel soldiers broke out in Juba last July, aborting the peace deal Beijing helped negotiate, Chinese peacekeepers abandoned their posts at a POC camp at least twice, according to a UN report. Witnesses also said Chinese peacekeepers fired teargas on civilians seeking protection at a UN site to drive them back to their camps once the fighting had subsided. China’s foreign ministry has called these allegations “malicious speculation.”

John Kueth Pouk, chairman of POC 1, was in the camp when the Chinese left. Many of the IDPs are of Nuer ethnicity, the country’s second largest ethnic group that often supports the opposition against the mainly Dinka-run government. Like many others, Pouk feared that government soldiers would attack the camp residents. The Chinese peacekeepers guarded the camp until they themselves came under attack, losing two soldiers.

“That’s when they left,” Pouk says, sitting at a plastic table in the community center of POC 1 that serves as their de-facto seat of local government. More than 30 people from the camps were killed and dozens of women raped during and after those four days of fighting, according to Pouk and other accounts. While the remains of the slain Chinese peacekeepers were airlifted back to China and carried by honor guards, POC 1 residents were burying their dead on the side of a road in the camp by a fence.

Testing ground

Other humanitarian efforts have been hamstrung by local circumstance. At Juba Teaching Hospital, a team of doctors from Anhui province hasn’t been able to work because the machine that sterilizes surgical equipment is broken. Chinese-donated solar powered traffic lights, installed in 15 junctions across the city, now don’t work because the panels have been stolen.

The Chinese embassy won’t give a dollar amount for how much Beijing has donated, because it says, most of its contributions are in kind rather than in cash. Since 2011, China has donated “20 batches of assistance,” whether that is aid and disaster relief items like rice, oil, medicine, and tents, or office equipment and vehicles for the government.

According to one tally, based on pledges made, China has given about $49 million (p. 18) in humanitarian aid to South Sudan since the civil war began. That’s a little less than half what the United States, South Sudan’s largest donor, had given as of 2015.

This year, of $1.4 billion given to South Sudan in humanitarian aid, 40% came from the United States and less than 2% of funds were from China, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’s Financial Tracking Service, which tries to capture all reports of humanitarian flows.

The difference is not lost on critics within South Sudan. The country’s former finance minister, David Deng Athorbei last year, described China as “taking our oil but doing nothing to help South Sudan.” In defense, Zhang says China is still a developing country, and that its donations in South Sudan are a form of “help of among poor brothers,” not assistance “from a donor to a less developed” country.

Few in South Sudan will be convinced by this argument, evidence of how expectations have mounted for the world’s second largest economy as it becomes more involved around the world. “In general, the feeling that China has not done enough at the time when we need their help is widely held,” says Moro, the professor at Juba University.

On a continent where many focus on the influence China has on its African partners, rather than the other way around, South Sudan is an example of how local political realities have stymied attempts by one of the world’s most powerful countries to manage events in its interest.

China’s mistake, according to Patey, was focusing on bringing the country’s warring sides together to ensure protection of Chinese investments and nationals—rather than working more closely with regional and foreign players to build consensus on ending the crisis. “Beijing was trying to do too much on its own in South Sudan. Much like other foreign and regional players, it prioritized its economic interests over long term peace building,” he says.