How a simple three-digit number helps websites stick it to online censorship

Last week, the American gossip site Gawker published a piece about Rebekah Brooks, former CEO of Rupert Murdoch’s News International. Lawyers for Brooks, who is facing criminal charges in the UK relating to alleged phone hacking by the News of the World newspaper, quickly slapped Gawker with a cease-and-desist letter accusing it of potentially prejudicing the outcome of the trial, which would violate UK law. Anyone in Britain who now visits the Gawker page in question is greeted with large, not-terribly-friendly letters that say:

Last week, the American gossip site Gawker published a piece about Rebekah Brooks, former CEO of Rupert Murdoch’s News International. Lawyers for Brooks, who is facing criminal charges in the UK relating to alleged phone hacking by the News of the World newspaper, quickly slapped Gawker with a cease-and-desist letter accusing it of potentially prejudicing the outcome of the trial, which would violate UK law. Anyone in Britain who now visits the Gawker page in question is greeted with large, not-terribly-friendly letters that say:

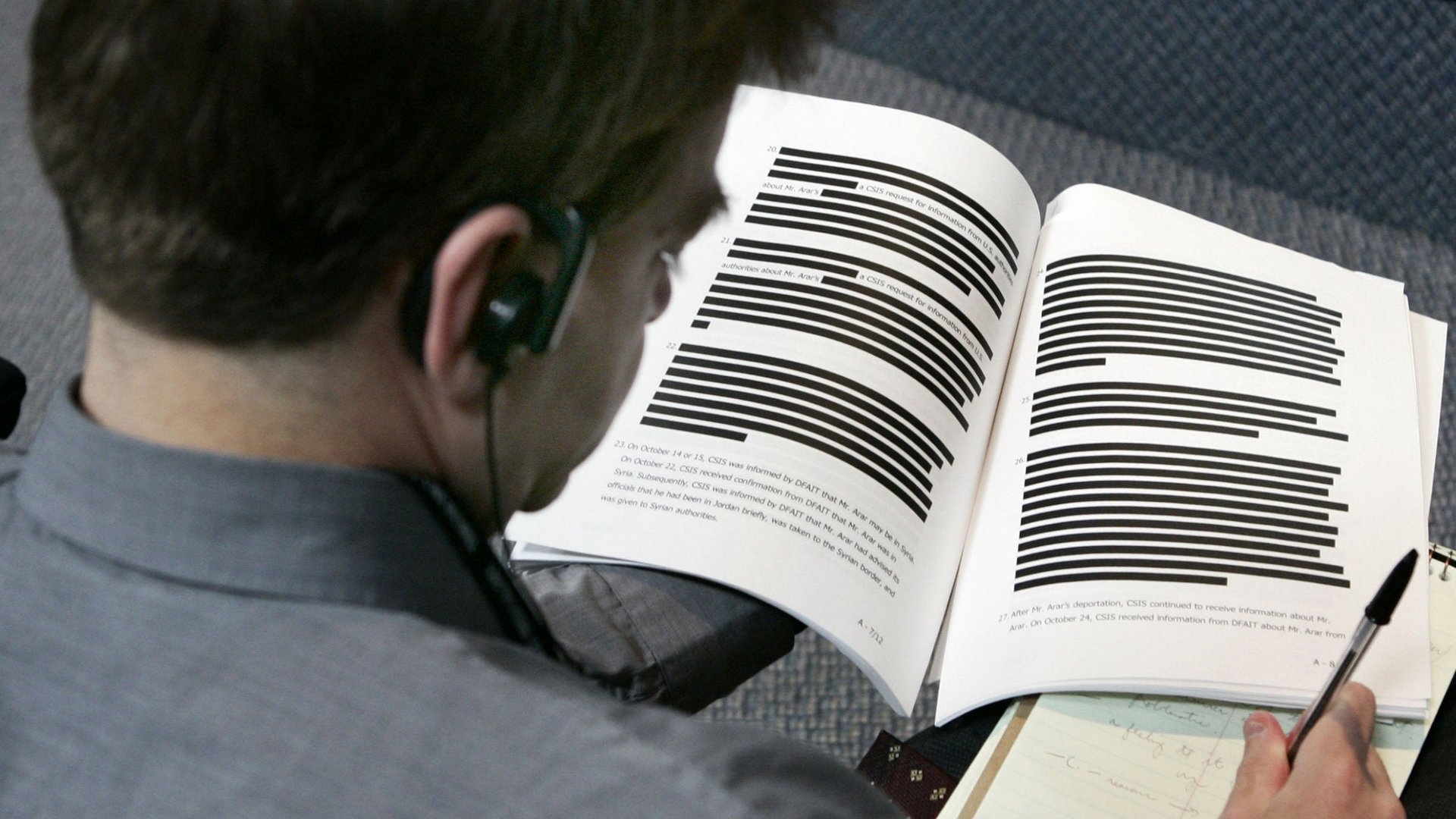

Error 451 freedom of speech not found

Error 451 is an internet status code, a dull but necessary piece of the web’s architecture. These codes are like traffic signals: Whenever computers exchange information on the web they send each other codes, which essentially say things like “Got your request, I’m still working on it” (code 202) or “you won’t find that here, look there instead” (code 308). There are dozens of these codes, including the occasional gag (Error 418: I’m a teapot).

You’re probably familiar with “404 Not found”, which a server spits out when it can’t find the page you’re looking for. In the past, that’s what UK web users might have seen when they went to the Gawker page. The 451 code, however, is a more pointed way of signaling that something has been taken down or blocked because someone didn’t want you to see it.

Code 451 hasn’t yet been formally adopted by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), a voluntary body that handles such things. But Gawker’s use of it isn’t new. Earlier this year, Mozilla also adopted a 451 code, which it will use when an app for its new Firefox operating system for smartphones “is unavailable for legal reasons, perhaps due to region or content restrictions.” Last month Philip Pemberton, a British software engineer, received a copyright infringement notice for posting an article from another site that was subsequently put behind a paywall, and explained how he would use a 451 code for such cases.

Having a special code just to say that a page is missing because of a legal demand might seem like little more than a nicety. But Tim Bray, a Google engineer who is a member of the IETF and wrote a draft document on how to use 451 (though he’s quick to say it wasn’t originally his idea) says it’s important for both engineering and policy reasons. “If we are going to be good engineers and caretakers for the internet infrastructure, we need to understand when breakage occurs and what the reasons for the breakage are,” Bray told Quartz. From a policy perspective, “there should not be a mysterious silence like in China, where you just get met with internet breakage.”

And while the status code numbers themselves are fixed by the IETF, websites can often decide what message to display next to them. (With 404 errors, these are often extremely creative.) Gawker’s “freedom of speech not found” is perhaps on the snarky side. Bray’s draft is more subtly phrased:

451 Unavailable for legal reasons

The point of a 451 starts to make more sense when you start looking for things you’re not supposed to see. Several commercial services do have some sort transparency in place—for example, YouTube explains when a video is not available because of a copyright notice and Hulu does the same if you live outside the United States. But government-imposed bans are rarely as transparent. When I tried loading The Pirate Bay, blocked in the UK since last year, in London earlier this morning, my ISP redirected me to http://www.siteblocked.org/piratebay.html, which does not load at all. But if I try to connect to Fenopy, another blocked file-sharing site, my browser simply returns a “404 page not found” error message.

Bray doesn’t expect Error 451 (the number is a nod to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, a novel about a future world in which books are illegal) to become a web standard in less than a couple of years. But after Gawker’s experience, online publishers may very well decide to push it into the mainstream long before that.