Clinical trials are under fire, but as doctor with a rare cancer, I’m glad they exist

Cancer is rarely far from the front page, and it recently added one more prominent member to the club. Already having returned to work, Arizona senator John McCain has not let his glioblastoma diagnosis slow him down. I respect McCain for his willingness to share his diagnosis so quickly, so publicly, and at a time when he stood up as a critical, influential voice in the debate regarding the future of healthcare. Standard treatment for glioblastoma involves surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, and new therapies are being actively studied. But what happens when there is no standard treatment protocol for a very rare cancer?

Cancer is rarely far from the front page, and it recently added one more prominent member to the club. Already having returned to work, Arizona senator John McCain has not let his glioblastoma diagnosis slow him down. I respect McCain for his willingness to share his diagnosis so quickly, so publicly, and at a time when he stood up as a critical, influential voice in the debate regarding the future of healthcare. Standard treatment for glioblastoma involves surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, and new therapies are being actively studied. But what happens when there is no standard treatment protocol for a very rare cancer?

As a physician and patient with a rare cancer, I had decided to keep my diagnosis and treatment fairly private, not letting this diagnosis define me. For the past year and a half, taking care of myself and my patients was the immediate priority. But now I am ready to lend my voice to the healthcare conversation. And I wish to shed light on an important topic that is not commonly discussed: participation in a clinical trial.

On Feb. 19, 2016, I was a 42 year old newlywed, at the beginning of an exciting new chapter, when my life was forever changed by cancer. A mass found on imaging, a biopsy, a diagnosis. Just as one imagines, everything came crashing to a halt. As a physician, I recognize that I received exceptional care, and saw experts at three leading cancer centers in the span of one week. The scary truth: there is no standard of care for my cancer. It’s called an epithelioid sarcoma, a rare tumor that originates from soft connective tissue below the skin (such as fascia, tendons, muscles). This exclusive club admits 1 in 2.5 million people.

During this crash course in an ultra-rare cancer, I was a student again. I learned about available treatment options including chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which seemed to have high risk and side effects and limited benefit in treating this tumor, and the ultimate goal of surgery to remove the tumor. And, I learned about a recently opened Phase 2 clinical trial involving a novel medication that was being studied in patients with solid tumors that have the same molecular marker as my cancer. I was a perfect candidate for the study, but faced differing opinions about what I should do.

According to the American Cancer Society, in the United States, only 5% of American adults with cancer participate in clinical trials to test a new drug or device. For new drug development, there are several different phases of clinical trials. Phase 1 clinical trials evaluate the safety and side effects of a new drug; Phase 2 assesses if a new drug is effective in treating a specific condition; Phase 3 compares the safety and effectiveness of the new treatment versus the standard treatment. Lastly, after the treatment is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, Phase 4 trials study the long-term side effects. In cancer clinical trials, placebo treatments are rarely used.

Virtually all of the landmark cancer drugs came to the market after cancer patients participated in clinical trials. Examples of cancer drugs that revolutionized treatment include Herceptin for certain types of breast cancer, and Gleevac for certain types of leukemia and stomach cancer.

Two medical oncologists and several of my colleagues encouraged me to consider enrolling in the trial: epithelioid sarcoma is a slow-growing tumor, the study medication has minimal side effects, I was guaranteed to receive study drug (no placebo), and I could continue to work.

I tried to ignore the reality of, well, my reality. Instead I buried myself in my work, preferring to concentrate on being a physician, taking care of patients rather than being one. After weighing the good and the bad, the benefits and the risks of each intervention, I decided to enroll in the study. Why not try it for eight weeks?

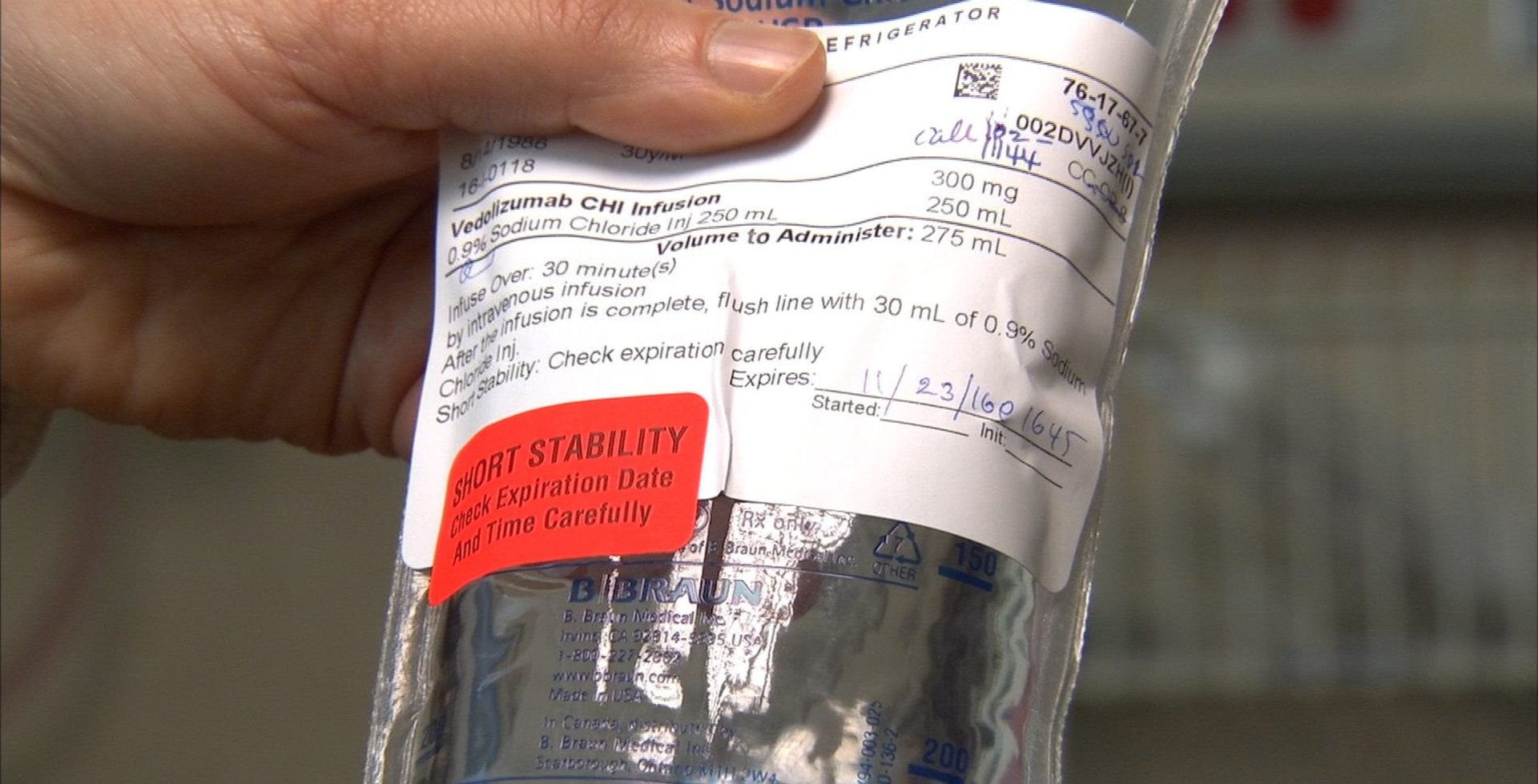

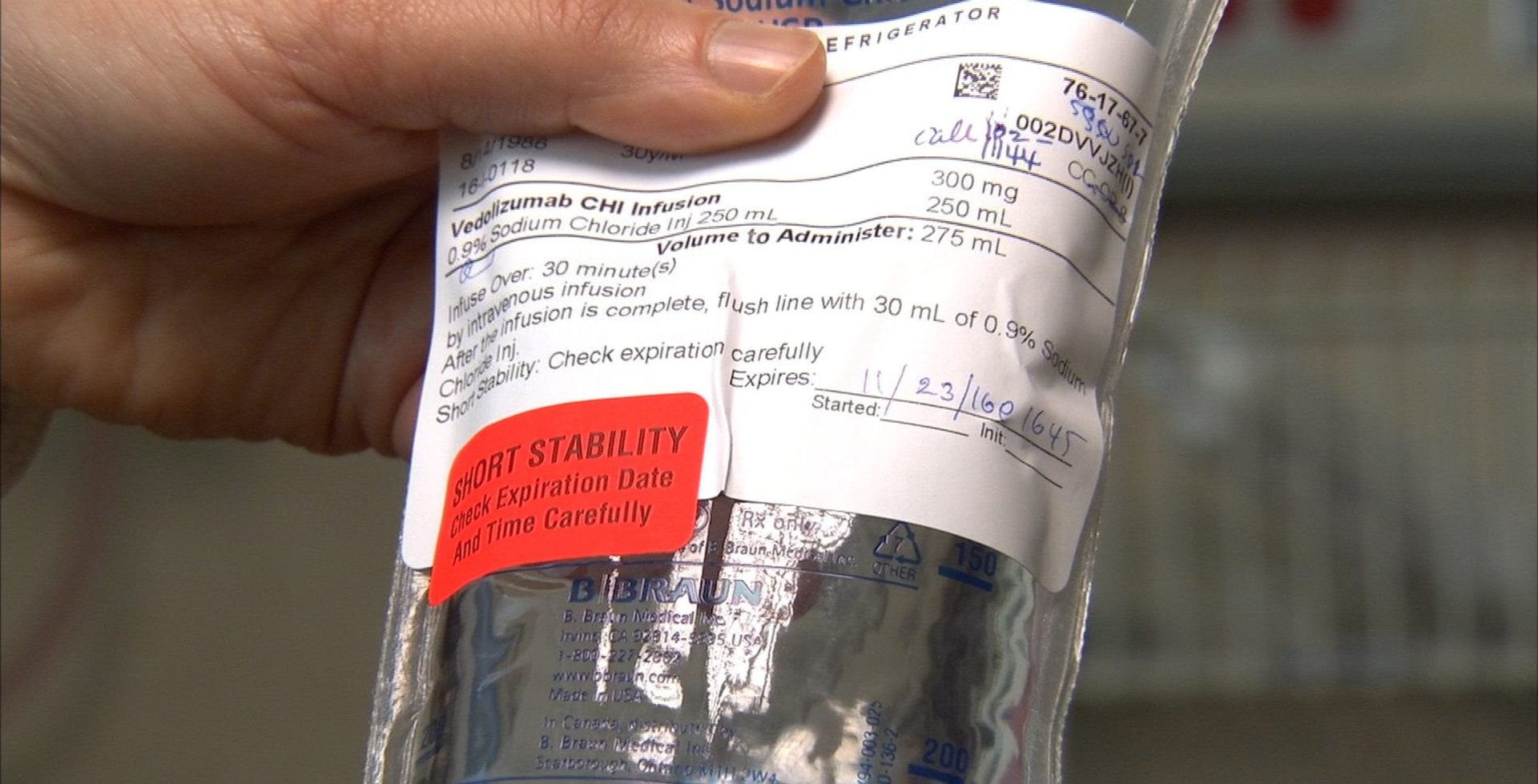

Being in a trial is a commitment. I spent countless hours undergoing additional testing, attending doctor’s appointments, sitting in waiting rooms. I faced the challenge inherent in going from being the expert others seek out to needing to trust my team of experts. I learned to carry my computer or a book with me at all times, knowing I’d spend more time in the waiting room than with my medical team. After my first eight weeks on study drug, my tumor shrank. So we forged ahead with another eight weeks of treatment, always knowing that the future was uncertain. My life was distilled to eight-week blocks of time. Fortunately, on study drug my tumor decreased in size so significantly that surgery was deferred until October.

Epizyme, the company that makes the study drug, Tazemetostat, shared the following in a recent press release: “The epithelioid sarcoma cohort in Epizyme’s Phase 2 study represents the largest prospective study of epithelioid sarcoma with any approved or investigational treatment to date…The cohort was initially designed to enroll 30 patients, and was expanded to enroll an additional 30 patients in December 2016 based on encouraging early activity.” And with only 60 patients in the study worldwide, one of those good responders was me.

A recent article stated that there are too many experimental cancer drugs in too many clinical trials, and not enough patients to participate in the trials. Furthermore, the article questions whether this is the best use of healthcare resources. I benefited from recent advances in targeted therapies, where a drug tackles a specific mutation in cancer cells that allows the tumor to grow, and blocking this pathway for tumor growth can lead to cell death. If a new drug can help even a few cancer patients, it may teach us about other novel ways to combat cancer. As the patient, I need researchers and pharmaceutical companies to ask questions about very rare cancers and to seek answers.

To be sure, cancer patients may fear that participating in a clinical trial could negatively impact their health. They worry that their health will decline during the trial, the cancer will spread or the drug could kill them. As a physician, I see patients who are distrustful of clinical trials. There is no certainty in trials, and it often takes many participants in many trials to achieve a true medical breakthrough. Although poor study outcomes may get disproportionate media attention, the general public is unaware of the thousands of people who are helped each year because they decided to participate in a clinical trial, or the millions who benefit from others who participated in clinical trials. Lists of current clinical trials are available.

I encourage all patients, those with and without cancer, to inquire about clinical trials available to them and to consider clinical trials offered to them. Your contribution to medical science could yield significant benefits for you, fellow patients and future patients.

I wear many different hats depending on the time and place—physician, wife, daughter, sister, aunt, friend, teacher, colleague. I am passionate about my career in medicine, and expected that I would contribute to medical science through innovative patient care, education and research. I did not expect to have to fight cancer along the way. And now, cancer-free for nine months, I recognize that my participation in this clinical trial as a cancer patient, and more recently as a cancer survivor, may truly be my most influential act.