Scientists made robotic bees to one day study the ocean

What’s better than a robot inspired by bees? A robot inspired by bees that can swim.

What’s better than a robot inspired by bees? A robot inspired by bees that can swim.

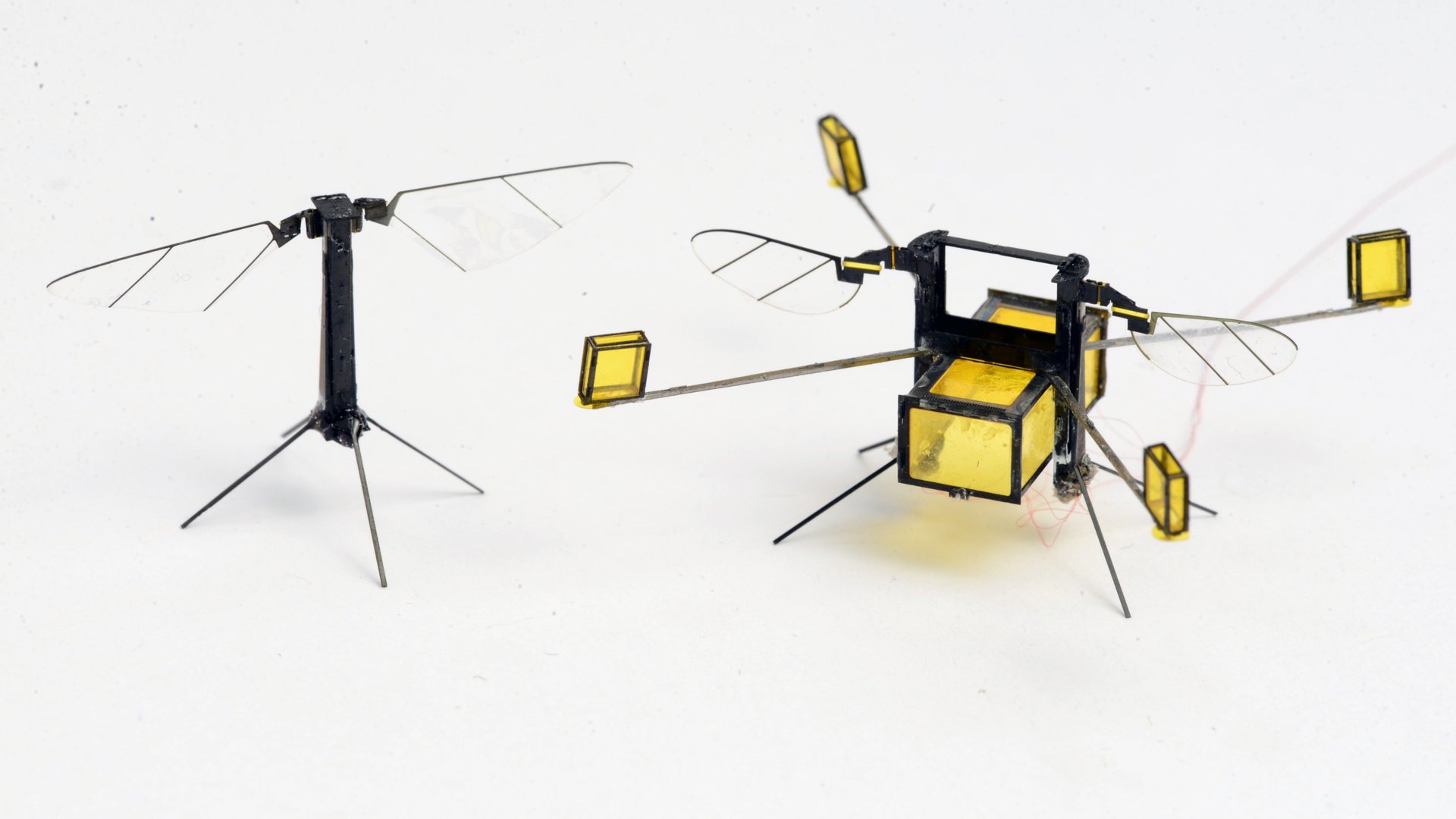

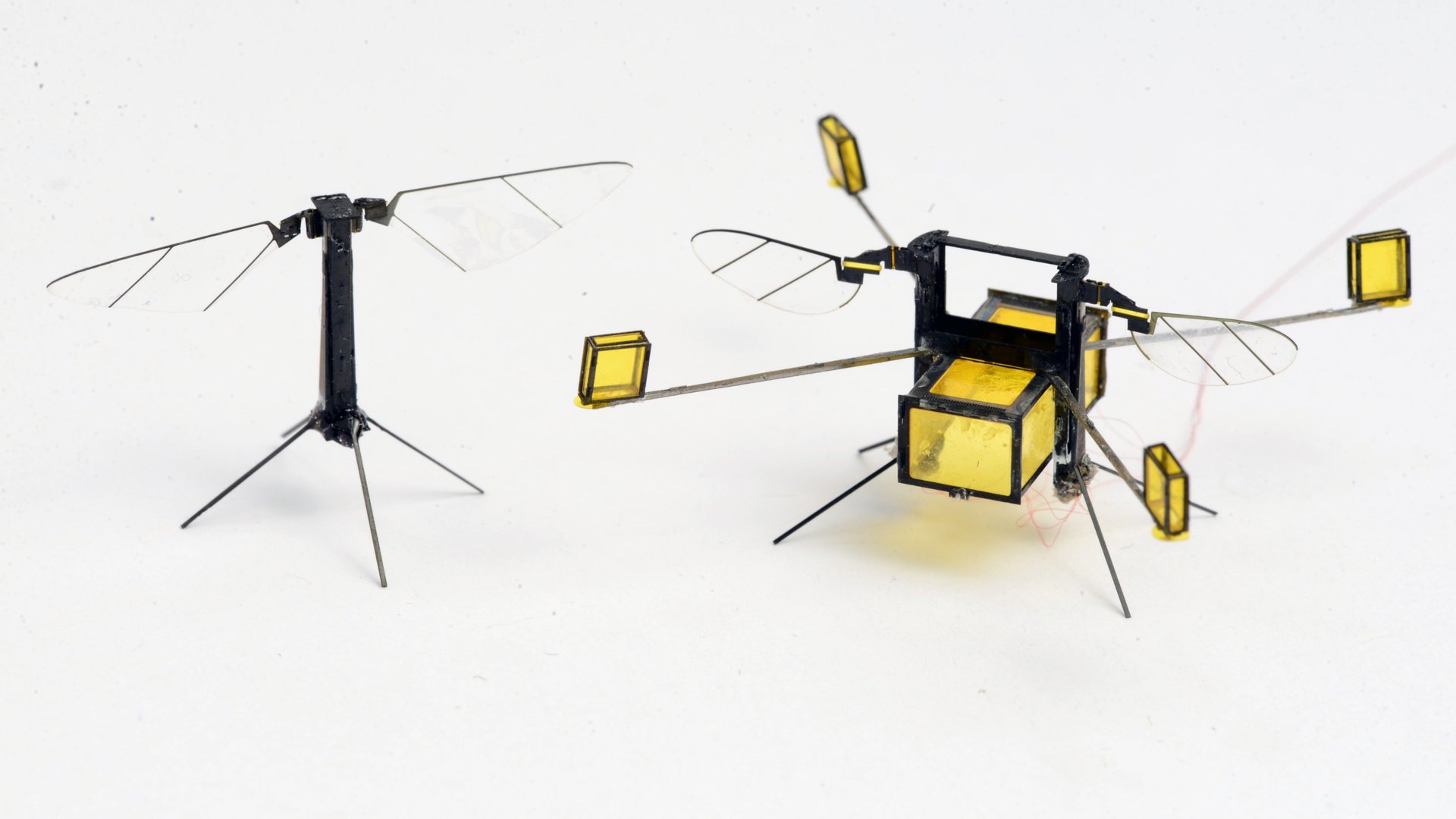

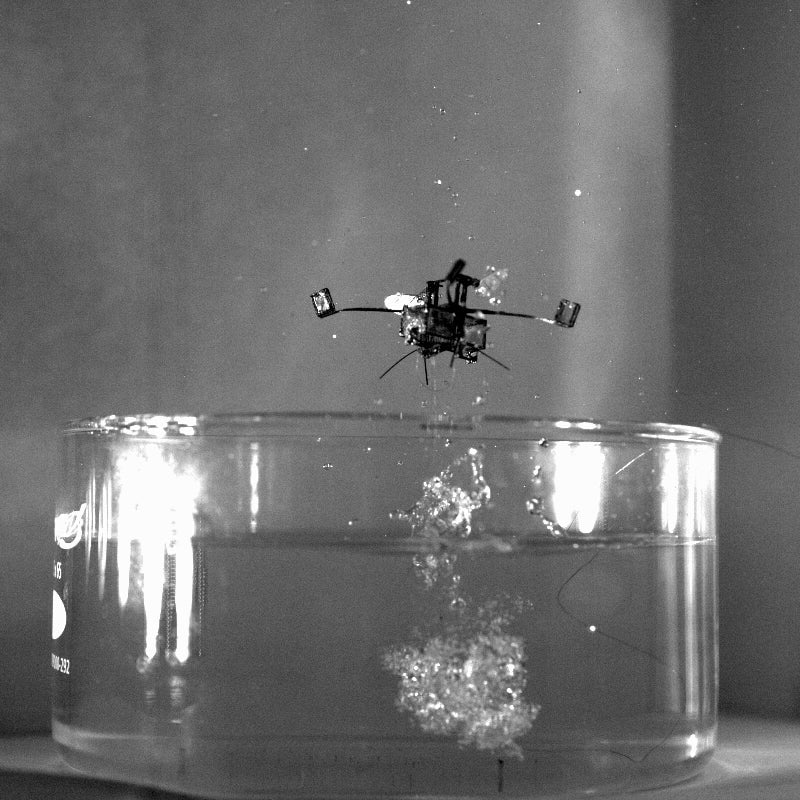

Researchers led by a team at Harvard University have developed a tiny, 175-milligram (about two feathers) device with insect-inspired wings that can both flap and rotate, allowing it to either fly above the ground or swim in shallow waters and easily transition between the two. Researchers think it will one day be used for environmental monitoring studies, according to Science magazine, which dubbed the device the “robo-bee.”

The research, which was published (paywall) on Oct. 25 in Science Robotics, builds on the work of another group of researchers who built a robotic fly four years ago. The new robot is twice as heavy, but with improvements that allow it to dip in and out of water. Instead of rotors like the ones on a helicopter, this one has wings that flap and paddle. They also have little stabilizers to keep the robot swimming upright while underwater.

Most importantly, the robots are equipped with their own little chemical labs to help them escape from water after they take a plunge. The “buoyant outtriggers” break down surrounding water into hydrogen and oxygen gases that build up underneath the robo-bee. After enough gas is generated, a lighter sets it on fire, the force of which shoots the robot about 30 centimeters (12 inches) into the air. It can’t fly when wet, but it can land gracefully to dry off after about a half a second.

Because these robots are so small, each part had to be made by hand. Researchers had to cut their own carbon fiber with lasers and assemble some of the parts together under a microscope.

It’ll still be years before these little gadgets are out flying and diving. For one thing, they can’t fly autonomously yet; they’re tethered to controllers and power sources. But eventually, researchers hope that they can be used outdoors for tasks like keeping tabs on fish and algae populations, water pollution, and even search and rescue missions to help keep rescue teams safe.