Why Boston bombing victims get millions when wounded soldiers only get thousands

To Ken Feinberg, if you lose both your legs, you’re as good as dead.

To Ken Feinberg, if you lose both your legs, you’re as good as dead.

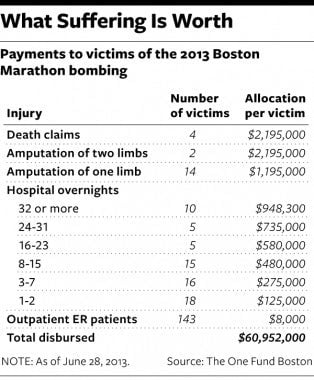

Here, in the world of the living, inspirational media stories after the Boston Marathon bombings featured survivors who persevered, grittily relearning to walk atop state-of-the-art prosthetic limbs, fighting for normalcy with each new step. But in Feinberg’s world, it made no difference whether a person could still live a rewarding life or never left the race’s finish line. That didn’t enter the equation—his equation. His choice. His rules. Whether you died at the scene or you lost both your legs, you received the same amount of money—$2.2 million—from the victim fund established in the wake of the attack. If you lost one limb, you received considerably less. If you were hospitalized but kept your limbs, then still less.

Feinberg is the nearly ubiquitous expert who has been called in to divvy up funds for the fallen and the injured in a stomach-churning sequence of tragedies, from the Sept. 11 attacks to the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, from the Virginia Tech shootings to the Boston bombings. He’s death’s accountant. When the stands collapsed at the Indiana State Fair in 2011, killing seven, they called Ken Feinberg. When a gunman murdered 27 children at Sandy Hook Elementary in Connecticut, they called Ken Feinberg. His is the grimmest of specialties.

“You’ll never make these people whole,” Feinberg says, sitting in his Washington law office as the city below baked in the summer’s heat. Befitting a career lived under klieg lights, one wall is dedicated to press clippings. But here, dread and devastation run though the framed articles, a sorrowful wall of fame. On the coffee table are we-couldn’t-have-done-it-without-you letters from Presidents Bush and Obama, along with a picture of Feinberg and family in the Oval Office. Opera, Feinberg’s passion, is piped into the room continuously.

And characteristic of a man who has waded repeatedly into tragedy’s wake, who has been praised and flayed, who has sent millions of dollars to some victims and told thousands of others they’ll see nothing, and who is viewed as the unparalleled expert in his field, Feinberg is alternately boastful and defensive, contemplative and bombastic. He’s done this so long now, he knows the questions before they come, addresses the criticisms before they’re raised, and stands by his record to the end. With this vocation, it seems, comes a nearly bottomless capacity for self-examination. Feinberg has written books and delivered commencement speeches on the principles of victim compensation, on the value of a life. He has a singular perspective on how our society chooses—or declines—to take care of its own. And it has left him troubled. “Bad things happen to good people each day in this country,” he says.

That is to say, not everyone gets a million dollars when tragedy calls. And by “not everyone,” that is to say just about no one. Feinberg’s entire public career is about the outliers—the handful of moments when the government, or a corporation, or a bevy of private citizens determines that a tragic event somehow merited a pecuniary response. Until 9/11, the government was not in the business of remunerating victims of terrorism; the closest it came to compensating on a mass scale was natural-disaster relief. But families of those murdered on that September day ended up with more than $2 million each, tax free. Feinberg says such an effort, funded by taxpayer dollars, will never happen again. “It’s against our heritage and character as a nation, frankly, to be establishing government funds to compensate for loss,” he says.

Indeed, victims of the first World Trade Center bombings in 1993 never saw any money, nor did the 168 killed and 680 injured in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Nor did the 13 troops killed and 30 wounded by a gunman at Fort Hood, Texas, in 2009. The Boston Marathon bombing, which killed three and injured more than 260 others, can be viewed as a test of whether Congress still wants to redress personal injuries caused by a terrorist attack. It doesn’t.

But if the government is out, everyday donors aren’t. The $60 million that Feinberg administered in Boston was all private money, which gave him license to disperse it any way he saw fit. Funds sprung up to assist victims of the shootings at Virginia Tech, Aurora, Colo., and Newtown, Conn. Obama persuaded BP to set aside $20 billion for businesses and communities harmed by the oil spill after its Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in 2010. Feinberg was involved in each of those efforts.

All of this raises fundamental questions of fairness, he says. On one hand, the 9/11 payout was an expression of political sentiment; few Americans objected. And as far as private money goes, well, that’s the marketplace in action. Donors are free to send checks in one case and not another, just like they’re free to choose between the Jerry Lewis telethon and the March of Dimes. On the other hand is the unsettling feeling that human life ends up being valued in all manner of disparate ways, based on publicity, geography, the nature of the crime, and the identities of the victims. “It’s horrible,” Feinberg says. A woman who lost a spouse in the Boston bombings will receive more than $2 million. A family who lost a child at Sandy Hook Elementary will see less than $300,000. Meanwhile, the families of African-American children killed by stray bullets on the streets of Chicago, Washington, New Orleans, and elsewhere may not be able to cover the cost of the funeral.

Some, not others

There are many reasons why the private victim fund has become the favored means to compensate victims of mass tragedy. Certainly, the 9/11 fund created a model in the public consciousness; it reemphasized the principle of a society collectively responding to disaster—and, more than that, it showed, largely thanks to Feinberg’s work, that compensation could be paid in a humane, effective, and efficient way. Other factors also play in: Technology has made donating easier than ever, while cable networks’ thirst for narrative can drive donations. Victims in some cases are elevated to the status of martyrs or even angels. Tragedies are lingered over for days at a time. In some ways, it canfeel like a telethon. “You’re totally at the mercy of what people have an emotional reaction to, what gets the most visibility, what plays out well as a story,” says Edward Lascher, a social-sciences professor at California State University (Sacramento) who has written about victim funds. “The potential for arbitrariness is pretty high.”

By and large, however, Americans have never made compensating victims of crime or tragedy a societal priority. It was, rather, a matter for criminal law, which provides for restitution in most cases. A perpetrator in an assault case, for example, is ordered to pay the victim’s medical expenses and lost wages as part of his punishment. The aim is to stave off another lawsuit to recover damages. “You don’t want the victim to have to navigate the civil system,” says Meg Garvin, executive director of the National Crime Victim Law Institute in Portland, Ore.—a goal that Feinberg has long shared. Except that, often, the perp pays nothing; and when he does, it only trickles out. Convicted swindler Bernie Madoff was ordered to pay $17 billion to his victims, but he was bankrupted by the same crash that evaporated his clients’ money. Some are just beginning to see partial payments.

A victims-rights movement that sprung out of the progressive criminal-justice reforms of the 1960s and ’70s led to state and federal programs intended to assist crime victims in the same manner as restitution, with basic payments to cover economic losses. But they are chronically underfunded (they draw money from fees and fines rather than from tax dollars) and often underused. They pay nothing on the order of the Boston fund or even the Newtown fund, because most states cap victim awards at $25,000. According to the National Association of Crime Victim Compensation Boards, less than $500 million is paid out annually to about 200,000 crime victims nationwide, an average of close to $2,500—almost 100 times less than the average Boston Marathon award.

In 2004, after Feinberg wrapped up the 9/11 fund, Julie Goldscheid, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law, compared the compensation given to three groups—terrorism victims, the more than 1,000 women killed that year as a result of domestic violence, and the 40,000 to 60,000 women who were sexually assaulted. The average 9/11 fund award, she noted, was $2 million, with payments ranging from $500 to $8.6 million. In 2001, the average award to crime victims through state victim-compensation programs was $2,400. “The contrast was just stark,” Goldscheid says, calling it part of an “unfortunate history of a narrative about deserving and undeserving victims.”

Private fundraising for certain classes of victims, she says, “opens the door to long-standing biases.” Nowhere might this be more true than in Chicago. At the time of the Newtown tragedy last December, 270 children under 18 had been gunned down on Chicago’s streets during the previous three years. One was 7-year-old Heaven Sutton, who was hit by a stray bullet while selling candy outdoors a few months before Newtown. Her family asked for donations to cover the cost of the burial and even setting up a table at her memorial service. “If you think about a victim of gang violence, they do tend to be kids of color,” Goldscheid says. “Is there a sensibility that they are somehow at fault?” According to the Illinois attorney general’s office, the maximum a murder victim or the family can receive from the state compensation fund is $27,000. (Litigating en masse against the gun industry is no longer a realistic option since Congress passed a law in 2005 granting broad immunity to firearms manufacturers.)

Lascher says a valid argument can be made for treating terrorism victims differently than everyone else because of the “psychic damage.” “The community really does suffer from some instances more than others,” he says. He adds, however, that it’s tough to draw a line between the Boston bombings and the Sandy Hook shooting. “If you are ever going to make a case for third-party trauma, it’s probably Newtown.”

But Newtown is also an example of the problematic nature of private victim funds, which can become politicized. Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy last month criticized the administrator of the fund, a foundation, for dispersing only $7.7 million of the $11.4 million to the families. It will use the rest to assist the Newtown community in unspecified ways. That means each family who lost a child will receive only $281,000 from the fund. “I was amazed,” says Feinberg, shaking his head. He was a consultant to the fund but not its administrator.

Lessons from misery

I first met Ken Feinberg 11 years ago at a claims hearings for the 9/11 fund. It was for Juan Cruz-Santiago, a Pentagon accountant who had somehow survived when American Airlines Flight 77 smashed into the building’s outer ring, where he was working. The inferno burned over 70 percent of Cruz-Santiago’s body and seared off his eyelids. He endured 30 surgeries and spent 12 weeks in the hospital, where doctors amputated his fingers.

Cruz-Santiago came with an attorney to ask Feinberg for an award akin to or greater than that given to a victim who had died in the attacks. Even then, Feinberg exhibited the mix of warmth and implacability that defines him, on one hand sympathizing with the victim’s suffering and on the other rejecting outright his lawyer’s efforts to inflate the award toward $3 million. Feinberg has written that he takes inspiration from the seated pose of Abraham Lincoln at the memorial on the National Mall. One hand is relaxed, showing his compassion toward the disloyal South; the other hand is clinched with determination to keep the Union together.

Feinberg works hard not to be swayed by emotional appeals—and he tries as best he can to keep some distance. “You sob in private,” he says. “Never in front of a victim.” As a rule, he does not visit the sites of the tragedies to which he has been connected. He avoided the marathon finish line and the Sandy Hook campus. He didn’t inspect Ground Zero in Manhattan until after the claims process was finished, and he never returned. Nor does he make a habit of visiting claimants in the hospital; he makes them come to an office, to keep himself from becoming entangled in their despair.

He broke his rule in Boston when he visited two victims at a rehabilitation facility—and he regrets it now. The first man, he says, greeted Feinberg with bitterness: “You’re going to give me a million dollars or more,” he said. “I’ve got a better idea. Give me my leg back.” The second victim’s legs were stippled by shrapnel and gangrene, but he still had them. He had been lying in bed doing the math, and he had a simple question for Feinberg. Should he have his legs amputated before the July 1 deadline for determining his award? The difference in his payout would have been more than $1 million, tax free. Feinberg didn’t know what to say. The man decided to keep his legs—and received $948,300. The first man, who lost one leg, received $1,195,000. Feinberg walked out of the facility that day and vowed: Never again. “There have to be limits,” he says.

The Bush administration tapped Feinberg for the 9/11 assignment largely because of his work assessing claims that arose from the 1984 Agent Orange settlement, which was then the largest mass tort deal in U.S. history. Brokered by legendary federal Judge Jack Weinstein, a mentor of Feinberg’s, the settlement fund paid $197 million to about 52,000 veterans exposed to the toxin during the Vietnam War, and to their families. The top payment was $12,800.

But the 9/11 fund was unlike any previous settlement. Passed by Congress almost as an afterthought in the rush to ensure that the domestic airline industry didn’t collapse in the wake of the attacks, the statute handed Feinberg a blank check and a fair amount of discretion—although nothing like he enjoys when he administers private money. “Congress didn’t know what a life was worth,” Feinberg says. “So it said, ‘Well, Ken will take care of it.’ ” After Feinberg accepted the job, another mentor, Sen. Edward Kennedy, for whom he had served as chief of staff, gave him some advice. “You make sure that 10 percent of the people don’t get 90 percent of the taxpayers’ money,” Kennedy said. “Be careful.”

Out of his 9/11 experience, which had its share of rocky moments, Feinberg developed a set of principles he’s used ever since: Be fair. Be up-front about the process. Give victims and their families a chance to vent. Try to evaluate applications with a minimum of paperwork. Don’t get bogged down assessing each claim like an insurance company or a court would. Don’t try to figure out someone’s future earnings. Or how long they’re going to live. Or the extent that one victim is more injured than another. “If I took time to examine everybody’s medical records, how can I get money out the door?” he says of his Boston work. “I’d be swamped. It would be New Year’s before the money would get out.”

To Feinberg, who takes jobs like the Boston fund pro bono, that’s the most basic tenet of all: Victims, he says, don’t believe a compensation process will work until the checks move. “Nothing is more important than getting money out the door,” he says. The Boston attack took place on April 15. In May, Feinberg stood before a crowd at the Boston Public Library and explained the uncomplicated criteria he would use for distributing money: Death and double amputation, single amputation, hospital stay, outpatient care. That was it, and that was the hierarchy. A month later, he held claims hearings. The first checks went out within 60 days of the bombing.

There were a few hiccups: One man sought $2 million for an aunt who had been dead for a decade. Another woman faked the documentation of a traumatic brain injury, won a $484,000 award, and was then caught and arrested. But only one victim, Feinberg says, wrote him to complain about his award, a man who lost an arm. He said that $1 million simply wasn’t going to cut it. Feinberg had long ago decided not to distinguish between a lost arm and a lost leg. And not to give a wealthy victim any less than the one who makes $68,000 per year and has to support five kids. “Most tort lawyers would say, ‘Ken, don’t you dare give both of those victims the same amount.’ I disagree,” he says. “I’m not prepared to say to someone they don’t need a million dollars.”

Plenty of people didn’t see a dime. Feinberg immediately ruled out compensation for mental distress—nothing for those who witnessed the explosions or who were showered with the blood of victims; nothing for the first responders who had to treat the shattered bodies. “Start paying everyone who has mental trauma?” he asks. “I got trauma watching on CNN.” Property damage, no. Economic losses, no. Forget that Boylston Street was shut down for the investigation and cleanup. Forget about the city being on lockdown while the Tsarnaevs were pursued.

Boston was as simple as anything like this was going to be. Money was plentiful, and Feinberg had grown up in nearby Brockton. (His accent makes it sound like he never left.) Still, the carnage, the amputated arms and legs, will linger with him. “This was the worst experience I’ve had,” he says. “In 9/11, you either got out of the buildings or you didn’t.”

Exceptions, not rules

I tell Feinberg that I can’t help but think of the waves of young soldiers who’ve returned from Iraq and Afghanistan with missing limbs. He nods. “They didn’t get a million dollars.” And they can’t. (Disability benefits for military amputees top out at around $7,800 per month.) We place soldiers in a different category than innocent victims, because they signed up to put their lives on the line. They undertook—and are paid for—the risk.

But what if the risk they assumed doesn’t cover being gunned down away from the battlefield, within the confines of their own military base? On Nov. 5, 2009, Maj. Nidal Hasan, an Army psychiatrist, opened fire with a semiautomatic pistol at Ford Hood, killing 13 and wounding 32 more before he was subdued. He now faces court-martial on murder charges.

Since the attack, the Obama administration has been locked in a debate with the victims over whether Hasan, a Muslim radicalized by a Qaida cleric while America was at war, committed an act of terrorism. The White House and the Defense Department call it “workplace violence,” since Hasan is not technically considered an enemy, despite arguments to the contrary from members of the Texas congressional delegation and other politicians. In a statement to Fox News last week, Hasan said the U.S. is “at war” with Islam.

The victims’ families and the survivors of the attack have taken the unusual step of suing the federal government for damages, alleging that the administration’s failure to label the attack as terrorism has resulted in reduced levels of financial and medical benefits because their injuries have been deemed unrelated to combat; they also charge that the FBI and the Pentagon failed to identify Hasan as a threat. The government has asked the court to delay the suit until after Hasan’s trial.

Kimberly Munley, a civilian police sergeant who was wounded when she tried to stop Hasan and who was seated next to Michelle Obama at the 2010 State of the Union, told ABC earlier this year that the president had broken his promise to help the shooting victims. “We got tired of being neglected,” she said of the lawsuit. Munley’s lawyer, Reed Rubinstein, wonders why the government was so quick to compensate the Pentagon victims of the 9/11 attacks and hasn’t showed the same generosity with the Fort Hood victims. “From a public standpoint,” he says, “people assumed the government was going to take care of its own.” Rubinstein, who practices in Washington, says his plaintiffs have noticed the millions, too, that poured into the Boston Marathon fund. What, after all, is the difference between that terrorist attack and this one?

The lawsuit faces serious and perhaps insurmountable obstacles in court; the government is likely immune. But Rubinstein could find encouragement in a June ruling by the British Supreme Court, which held that families of British soldiers killed in Iraq could sue the U.K. government for negligence if the soldiers received improper equipment and training. The ruling has no applicability to U.S. troops, but it could represent a trend toward holding the military accountable for negligence in ways courts haven’t before.

In the meantime, Rubinstein, mindful of the long road ahead, has been considering other ways to help his clients. “I’ve been thinking about starting up a nonprofit fund,” he says.

Building a model

Feinberg has always worried that the 9/11 fund set a bad precedent. “If Congress had thought about it a couple of more weeks, they probably wouldn’t have passed it,” he says. He frets about creating a culture of victim entitlement, which is why he thinks nothing like the fund will ever exist again.

Others aren’t so sure. Lascher, the Cal State professor, says government may have to step in if there’s another large-scale terrorist attack. “We really do recognize that people suffer disproportionately, and we have an obligation to take care of them,” he says.

But another part of Feinberg’s legacy, his work on the BP oil spill, may last the longest. In a sense, what the company did was more radical than Congress’s creation of the 9/11 fund—deciding to set aside $20 billion to avoid protracted litigation. Nothing, not even 9/11, created more headaches for Feinberg than the spill. Claimants all along the Gulf Coast grumbled that he was moving too slowly. Local politicians griped about his methodology. Trial lawyers felt aced out of the action after victims waived their right to sue. And it didn’t entirely work: BP remains locked in a lawsuit against other claimants in New Orleans.

The BP fund put Feinberg in an odd position. He has maintained throughout his career (and in his private work settling claims for corporations) that there are better alternatives to a trial. He rankled some in the plaintiffs’ bar when he explained to claimants why they should waive their right to sue: They got their money from the fund quickly, and no lawyer would take a cut. But he also resisted attempts by pro-business forces such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to hold up his efforts as an example of a reshaped American legal system. “I’m a lawyer,” Feinberg said in a speech to the chamber three years ago. “I happen to believe, in the run-of-the-mill, everyday life in America, the legal system works pretty well.”

At the same time, he recognizes that the environment for litigation—and particularly mass class-action suits—has worsened dramatically since his Agent Orange days, because of hostility from the courts, Congress, and state legislatures. Cases must more often be heard individually (if at all), which can clog court dockets. As an alternative, in situations where liability seems clear, “one has to look toward some sort of an informal process” other than litigation, says Robert Rabin, a professor at Stanford Law School. “The tort system was never superefficient. The question is whether the tort system is still the way to go” when 90 percent of all cases end up settling. It’s something that airlines—which can be quick to settle claims after a crash—have known for years. Hospitals, too, are realizing that admitting to medical error, engaging the patient quickly, and disbursing money results in far fewer malpractice suits. That’s the Feinberg Way.

Feinberg has seen it himself, beyond BP, which he calls a tremendous success story, because the vast majority of claimants avoided the courts. The Virginia Tech shootings served as another model. Because that fund was private, the 200-plus applicants didn’t have to surrender the right to sue the university. Still, only two did. Feinberg credits the lessons he learned from the 9/11 fund: Treat people well, give them some money, and they don’t sue. To that end, Penn State University brought him in last year to quickly (and quietly) settle claims relating to the Jerry Sandusky sexual-abuse scandal, where, again, liability isn’t the issue. Even the 9/11 fund has been revived in an effort to ward off litigation from first responders who say they suffered health problems from exposure at Ground Zero. Now they can apply to the fund for compensation, though the job will be tougher because the amount of money that can be awarded is capped. Feinberg had unlimited government funds the first time around. (He isn’t involved this time.)

But there’s the legacy, and there’s the man himself. And the need for his special expertise shows no signs of abating. After my second interview with Feinberg, he went to Capitol Hill to give advice about how to distribute money collected after 19 firefighters were killed battling Arizona wildfires. (What would he tell lawmakers? “Take the money. Divide it by 19. And get it out.”) Life, Feinberg says, guarantees misfortune. The wolf is always at the door.

The work has taken a toll. When it gets bad, Feinberg retreats to a soundproof room in his home and cranks up Wagner or Verdi. It’s been his curative since he was a child. “Shut that door, and you escape.” Opera, he says, is the height of civilization, but “civilization is no guarantee against these horrors that we go through. Just because we live in a civilized society doesn’t mean we aren’t going to have these tragedies.”

You can stop whenever you want, I tell him. The next time a president, or a governor, or a mayor calls, you can turn it down. “No one would blame you if you said, ‘I’ve had enough tragedy for 20 lifetimes,’ ” I say.

“I’m not going to say no,” Feinberg replies. “I’m not going to say no.” And, to be sure, that call will come. It always does.

James Oliphant is the deputy magazine editor at National Journal.