After a mass shooting, Las Vegas can find resilience in its shady past

On the night of Oct. 1, Stephen Paddock fired from his 32nd floor hotel suite into a crowd of concertgoers in Las Vegas, killing 58 people and injuring hundreds. The shooting shocked the world, and reignited a debate over gun control in the US. What does the tragedy, and its aftermath, mean for Las Vegas?

On the night of Oct. 1, Stephen Paddock fired from his 32nd floor hotel suite into a crowd of concertgoers in Las Vegas, killing 58 people and injuring hundreds. The shooting shocked the world, and reignited a debate over gun control in the US. What does the tragedy, and its aftermath, mean for Las Vegas?

A deep dive into the city’s history reveals a place that is remarkably resilient, having survived depleted mines, the Great Railroad Strike, The Prohibition, Mafia wars, and devastating hotel fires. This turbulent history has given the city an unusual ability to bounce back that could prove vital in the days and months ahead.

From early on, Las Vegas struggled to find itself. On the basis of its location, climate, or resources alone, it had no reason to exist in the first place. Before development began in earnest in the 19th century, what we now know of as Las Vegas lay isolated, hundreds of miles away from major cities, on all sides cut off by lunar-like mountain ranges. Summer days could heat up to a furnace-like 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C). The only species fit to live in the barren, dusty, and rocky Mojave Desert were creosote bushes and chuckwallas.

Fortunately, a few artesian wells nourished some grassy areas. They functioned as an oasis for travelers crossing the Mojave Desert, explaining the first recorded settlement in the early nineteenth century. In 1829, Spanish Mexican explorers of the Antonia Armijo army, most likely guided by Ute or Paiute Indians, named the area “Las Vegas,” Spanish for “the meadows.” This moist patch first became a home for questionable activities.

In the early 1840s, Bill Williams, a Baptist minister who had become a mountain man and cannibal, used it as a base for his band of Indian horse thieves. Williams also worked as a guide for the US government taking armies across the desert, and was known to introduce hungry soldiers to eating “the long pig,” a euphemism for Homo sapiens. “In starving times,” an acquaintance of the preacher said, “don’t walk ahead of Bill Williams.”

In 1844, the wells were given a military purpose with the first recorded structure: a secret fort, built by explorer John C. Fremont to prepare for the war with Mexico. The war was won, the fort never permanently inhabited, but Fremont’s lasting influence on Las Vegas was putting it on the map. Fremont’s map inspired Mormons to settle in Utah. They built a 150-square-foot adobe fort meant to refuge travelers along the “Mormon Corridor.” Meanwhile, they used it as a base to baptize local Paiute Indians who, unappreciative, raided the fort’s crops and animals.

After three years, Mormon leadership gave up on the fort, and on Las Vegas, which one missionary described as the land the “Lord had forgotten” (there are many who would still describe it this way.)“It is easy to foresee that it will never become considerable,” two French cartographers wrote of Las Vegas in 1861.

But that year a large gold strike was reported in El Dorado Canyon. The Mormon fort was acquired by a group of men, and changed ownership a number of times, until Montana Senator William Clark purchased it in 1902. Clark wanted to make Las Vegas a “water stop” for locomotive boiler replenishing, servicing his proposed rail line from Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. Before the train rolled in, the Senator had already auctioned off all lots of the 110-acre “Clark’s Las Vegas Townsite” on May 15, 1905, the day that became the founding date of Las Vegas.

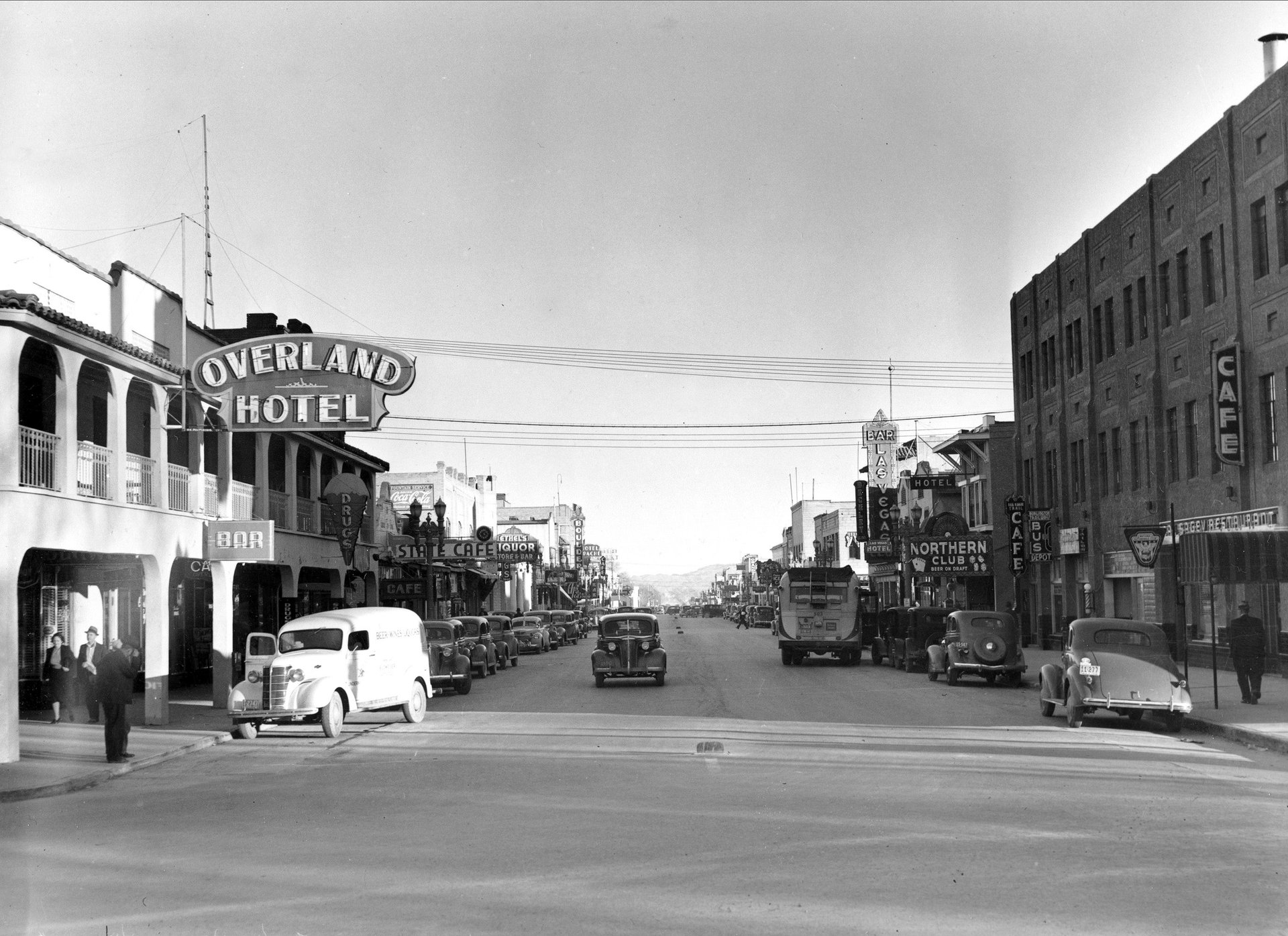

It was the promise of material wealth that finally led to the founding of the city. Las Vegas was born as a classic Western railroad town, one of many water stops along new railways that evolved into settlements. The mines and train brought customers for the speakeasies, brothels, and “sawdust joints,” small uncarpeted casinos with sawdust on the floor to soak up beer and tobacco spit. Even the layout of the city was very uniform. To more easily sell off Las Vegas’s lots, they were equal in size and laid out in a grid—a city layout dating back thousands of years, even before the Roman military camp.

But it would have been equally normal for Las Vegas to return to dust. In 1919, the mines ran out of ore. Three years later, Las Vegas workers joined the Great Railroad Strike. In retaliation, the railroad company moved its repair centers out of town. Without the railroad jobs, Las Vegas could have shared the tragic but common fate of new cities in the West. These cities were founded on serious risk. Their bustle could stop as soon as their mines were stripped, only to render them ghost towns, left to decay.

Desperately looking for another industry, Las Vegans established a Chamber of Commerce, which marketed the city as a resort city, out of envy for Palm Springs, the Californian desert city that successfully attracted tourists. In the 1920s, a few resorts and a golf course were constructed, and a Las Vegas lobby managed to include the city in the United States’s new highway system connecting Los Angeles to Salt Lake City—later known as the Los Angeles Highway, with a four-mile stretch that became the Las Vegas Strip.But few people came.

Who would have expected that the federal government, when it was at its most Puritanical, would not only come to help Las Vegas grow, but also indirectly mark it for a future of sin? In 1928, the government announced the federal construction of the Boulder (later named Hoover) Dam. It planned to dam the Colorado River to create cheap hydro-electric power, and to create Lake Mead for a freshwater supply. Las Vegas would benefit from all of this and, more importantly, since it was the closest city to the site, the dam would bring an even more valuable resource: dam workers, looking to drink and gamble their paychecks away.

US secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur—characterized by a reporter as “a very blue-nosed man”—planned to visit the city to look for a suitable place to house the dam workers. But Las Vegas had become notorious for clubs, brothels, and speakeasies illegally providing alcohol during Prohibition. Las Vegas was willing to let this industry go in exchange for the workers. Residents temporarily closed all drinking, gambling and prostitution dens, even repainting buildings, to show it was a place suitable to work in. Unfortunately, one of the secretary’s employees strayed, and was found with alcohol on his breath. The secretary retaliated. Instead of housing the workers in Las Vegas, he chose to build from scratch the “model town” of Boulder City, federally controlled and without vice. “Instead of a boisterous frontier town,” he said in his speech, “it is hoped that here simple homes, gardens with fruit and flowers, schools and playgrounds will make this a wholesome American community.”

Vegas merchants feared that their future was shattered. Nevertheless, by the spring of 1931, at least 42,000 unemployed workers came to Las Vegas hoping to find a job. At the abyss of the Great Depression, “the little desert town,” wrote Time, “has been swelling and swelling like a toadstool.”

Having tried to conform to the rest of the nation, but failed, Las Vegas finally decided to embrace its rebellious self. Business owners reopened the clubs and developed casinos and showgirl theaters, teaming up with organized crime figures and Mormon financiers. Despite the decision that workers would not be housed in Las Vegas, the city benefited from mostly male visiting dam workers who came at weekends searching for alcohol, prostitutes, and gambling—all of which were banned in the vice-free worker city.The intended separation of activities between Las Vegas and Boulder City resulted in each city supporting the other.

Ironically, for the same reason that Prohibition had led to the rise of organized crime, the Puritanical attitude of federal authorities opened a space for Las Vegas to thrive. The city stepped into providing niche services that most people at the time considered unwholesome or morally questionable, but for which there was still a market. Having unsuccessfully gone through multiple identities—a base for horse thieves, a military fort, a Mormon stronghold, a railroad town, and its latest unsuccessful attempt to provide a “wholesome” place to house the workers—Las Vegas understood there was profit to be made by being Puritan America’s “Other.”

The “otherness” of Las Vegas was further institutionalized through a whole set of “libertarian” state regulations ranging from taxes to marriage, conducive for business. In 1931, Nevada legislators lowered the minimum residency requirement for out-of-state divorce petitioners from three months to six weeks. Since many states had very strict statutes on divorce, divorcees fled to Nevada, and in particular to Reno, well-known as a place to get “Reno-vated.” Retaining a residency requirement was important, helping to fill hotels and guest ranches with divorcees.

That same year, the state legalized gambling, bringing about Nevada’s eventual forty-five-year, countrywide monopoly on casinos. Despite the Great Depression, Las Vegas’s resort industry grew. Divorcees passed time in guest ranches, while thousands of dam workers patronized the city’s nascent casinos: for instance the 1932 Hotel Apache, the city’s first hotel with an elevator and air-conditioning. State regulation, Nevada’s unique “commodity,” had a major impact on the city of Las Vegas, a city lacking other resources.

In the big picture, for the United States as a whole, by legalizing gambling only in remote Nevada it could be contained; for the same reason, the area would be a good site for nuclear detonations. Las Vegans realized their city’s remote location had been turned into an advantage. And as they built more casinos, the city would become the focal point of a national experiment in the legislation of sin.

Today, the city has already long lost its monopoly on sin. Hundreds of casinos have entered Indian reservations and American cities. True to its history, the city has adapted, by diversifying its economy from pure gambling to entertainment, and changing the casino from a gambling hall into a place for conferences, shows, nightclubs, and celebrity-chef restaurants.

Although the city’s founders played a risky game building a town in the middle of the Mojave Desert, they gave it a spirit remarkably resilient to the numerous threats it faced. As the city struggles to cope with the violent attacked perpetrated by Stephen Paddock, it will undoubtedly call on that resilience as it works to move forward.

Excerpted from The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of an American Dream (MIT Press). Copyright 2017.