Martin Luther’s defining act that sparked the Protestant Reformation probably never happened

The Catholic church of the 16th-century was rotten with corruption. Among other things, the Church was running a roaring businesses in indulgences, slips of paper excepting the holder from time in Purgatory, the interim step before rising up to Heaven. The more money paid, the more time off. One enthusiastic Dominican friar even claimed his potent indulgences could excuse the sin of raping the Virgin Mary.

The Catholic church of the 16th-century was rotten with corruption. Among other things, the Church was running a roaring businesses in indulgences, slips of paper excepting the holder from time in Purgatory, the interim step before rising up to Heaven. The more money paid, the more time off. One enthusiastic Dominican friar even claimed his potent indulgences could excuse the sin of raping the Virgin Mary.

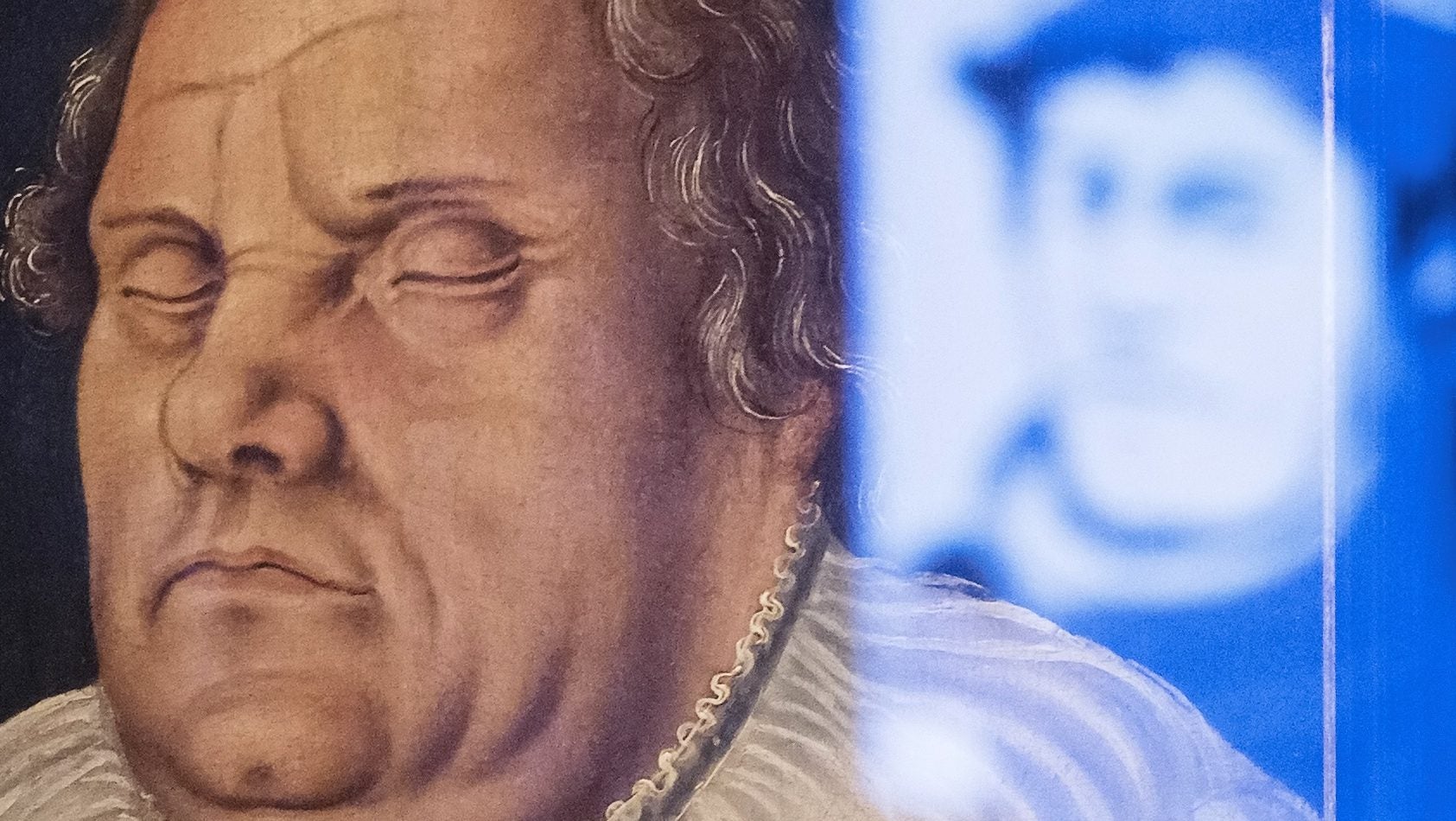

The German monk Martin Luther is celebrated this coming week in Germany for nailing his list of 95 theses to the wall of Castle Church in Wittenberg to combat this perversion of Jesus Christ’s teachings. His theses, penned in a fury at the Church in 1517, stated that the Bible (not clergy) were the primary religious authority and that faith, not deeds, were the prerequisite for salvation.

Luther’s defiance ultimately sparked the Protestant Reformation, a thunderbolt that cleaved the Catholic Church and led to the splintering of Christianity, as well as many aspects of what we think of as Western modernity. Today, almost a billion Protestants belong to hundreds of denominations around the world.

However, the defining event probably never happened, say religious historians. Writing in The New Yorker (paywall), Joan Acocella notes that most researchers of the period cast doubt on the idea that Martin Luther nailed his protests to the Castle Church for all to see. Reformation historian Peter Marshall concludes that the evidence is actually against it. That’s not to say the 95 theses didn’t exist. Instead, they were mailed to archbishop of Mainz on October 31, 1517 setting off an ecclesiastical crisis that remade the world.

Luther, of course, is a celebrity in his own time and ours. This year marks the 500th birthday of Protestantism, and Germans will take October 31 off as Reformation Day to celebrate Luther’s contributions. He remains the archetype of a rabble-rouser who defied the Pope, a hometown monk who made it big by redefining how we live today, even if he never picked up a hammer and nail to do it.