Four frightening facts Facebook disclosed at the Congressional hearing today

Facebook, Google, and Twitter disclosed a plethora of new details before a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing today (Oct. 31) about how Russia used their respective platforms in its attempt to influence the US presidential election. Top lawyers from each company again admitted that accounts linked to the Russian government were used to amplify fake news and spread divisive messages, and shared previously undisclosed information and figures.

Facebook, Google, and Twitter disclosed a plethora of new details before a Senate Judiciary subcommittee hearing today (Oct. 31) about how Russia used their respective platforms in its attempt to influence the US presidential election. Top lawyers from each company again admitted that accounts linked to the Russian government were used to amplify fake news and spread divisive messages, and shared previously undisclosed information and figures.

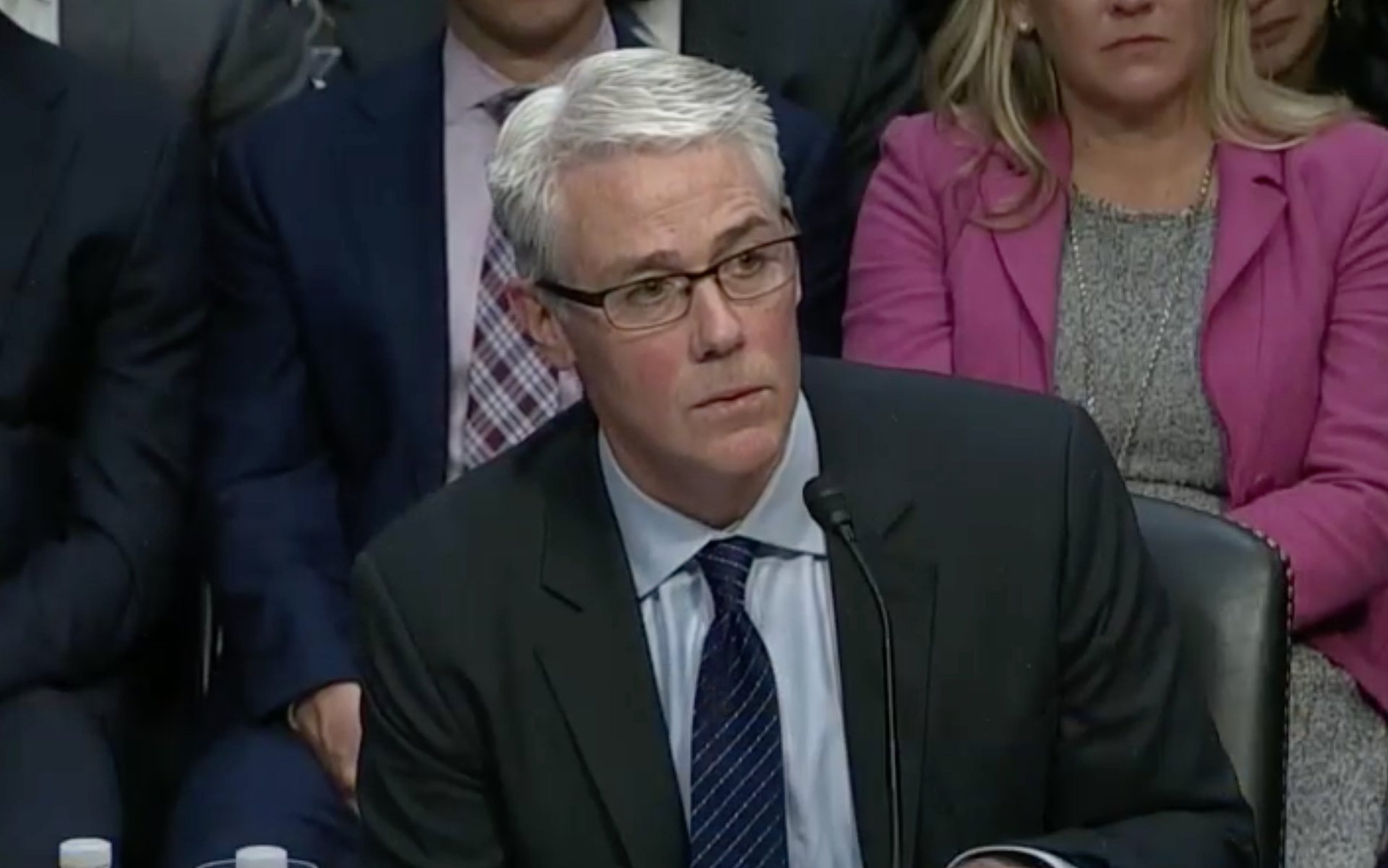

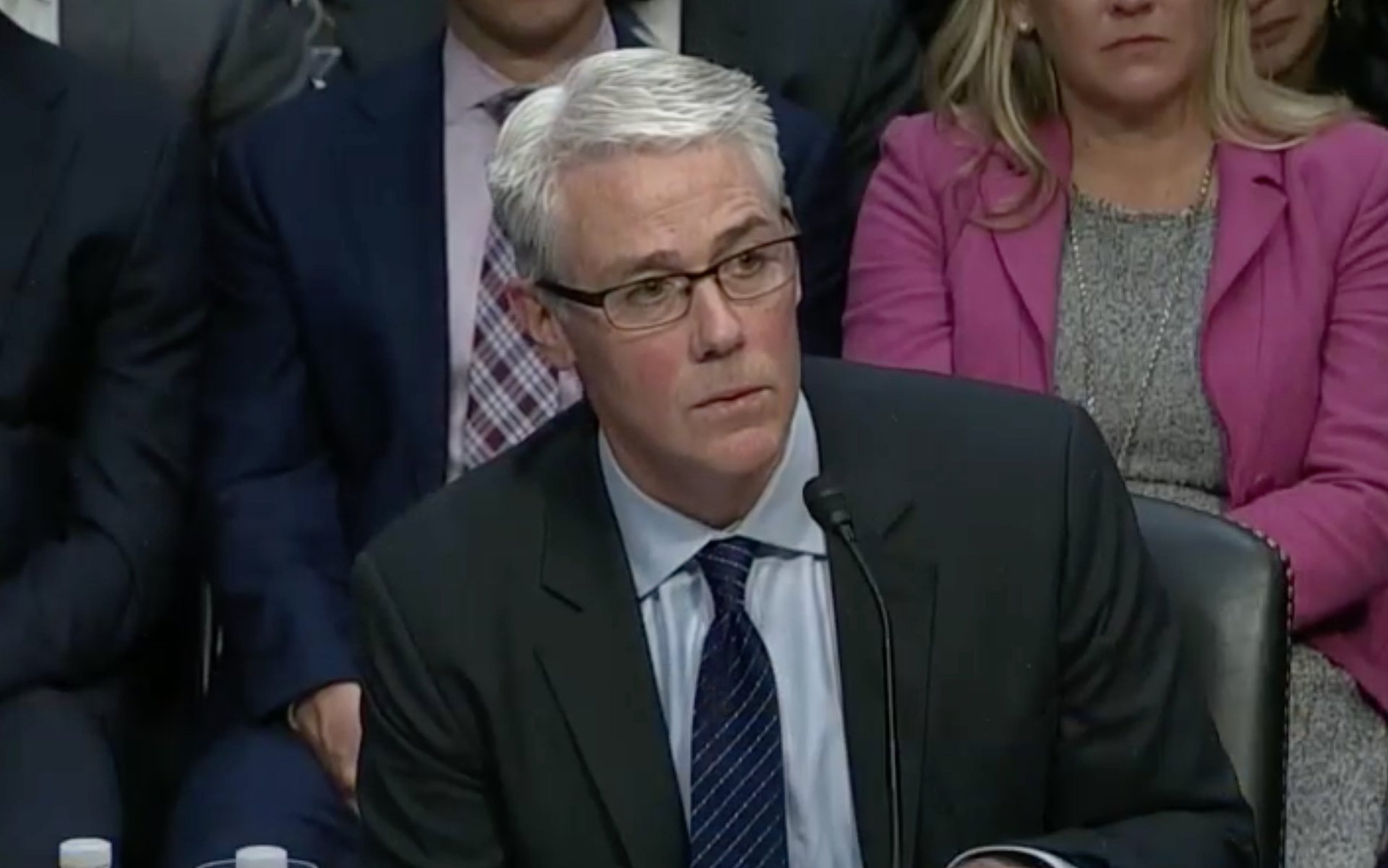

While all three companies offered a number of insights, questions from the senators were largely directed at Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch, leading to a multitude of revelations. We’ve listed the most troubling of those below.

1. 126 million people on Facebook saw ads bought by Russian-linked accounts

This figure was originally reported yesterday, after copies of Facebook’s written testimony were leaked to the press, but it remains one of the most significant details disclosed today. The number is a substantial increase from Facebook’s previous conclusion that only 10 million people had seen the ads purchased by Russian-linked accounts. Those 3,000 ads ran between June 2015 and May 2017 and cost about $100,000. They were “connected to about 470 inauthentic accounts and Pages” that violated Facebook’s policies. They focused largely on “divisive social and political” subjects like gun rights, immigration, and LGBT issues, and less on particular presidential candidates or the election itself.

2. Facebook can’t always determine who is paying for ads

After Stretch testified that the company currently has “approximately 5 million advertisers on a monthly basis,” Sen. John Kennedy asked how the company could possibly know who each of those advertisers are.

“You’ve got 5 million advertisers? And you’re going to tell me that you’re able to trace the origin of all of those advertisements?” Kennedy asked. He pointed out that advertisers could purchase ads through several shell companies to hide their identity.

“You’re telling me you have the ability to go—to trace through all of these corporations and find the true identity of every one of your advertisers? You’re not telling me that, are you?” the senator said.

“To your question about seeing essentially behind the platform to understand if there are shell corporations, of course the answer is no,” Stretch replied.

3. Russian activity on Facebook after the election was aimed at “fomenting discord about the validity of [Trump’s] election”

Facebook has reiterated on several occasions that the content pushed by Russian accounts on its platform was more focused on issues than candidates. Particularly, Facebook says, issues that tend to be polarizing and divisive. In his testimony today, Stretch said that following the election of Donald Trump, much of the content was aimed at raising questions over the legitimacy of the election.

“Following the election, the activity we’ve seen really continued in the sense that if you viewed the activity as a whole, we saw this concerted effort to sow division and discord,” Stretch said. “In the wake of the election, and now-president Trump’s election, we saw a lot of activity directed at fomenting discord about the validity of his election.”

4. Some of the Russian political ads were paid for in rubles, and Facebook didn’t catch it

A flabbergasted Senator Al Franken wondered aloud how a company like Facebook, with all of its data expertise, failed to catch this seemingly obvious problem.

“Mr. Stretch, how did Facebook, which prides itself on being able to process billions of data points, and instantly transform them in the personal connections with its users, somehow not make the connection that electoral ads, paid for in rubles, were coming from Russia?” Franken said. “Those are two data points—American political ads, and Russian money, rubles. How could you not connect those two dots?”

“I can tell you we’re not going to permit advertising, political advertising by foreign actors,” Stretch replied. “The reason I’m hesitating on foreign currency is it’s relatively easy for bad actors to switch currencies. So it’s a signal but not enough.”

Franken then pointed out that it might not make sense for a bad actor to switch to a currency like the Russian ruble or the North Korean won if they wanted to remain undetected by Facebook.