The Bank of England raised interest rates for the first time in a decade, and it’s not happy about it

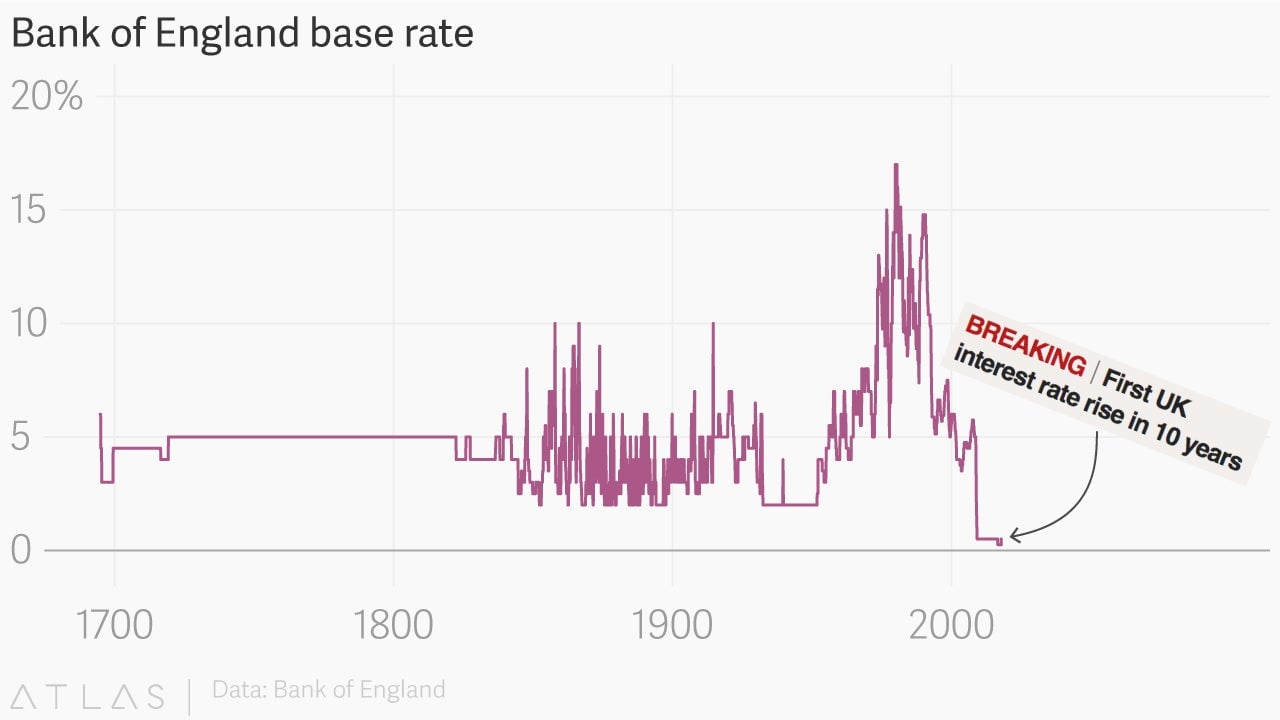

For more than a decade, the UK economy was deemed too weak to withstand an increase in interest rates. Today, for the first time since July 2007, the Bank of England hiked its benchmark rate (pdf) up from an all-time low. (The bank was founded in the late 1600s, so that covers a long time.)

For more than a decade, the UK economy was deemed too weak to withstand an increase in interest rates. Today, for the first time since July 2007, the Bank of England hiked its benchmark rate (pdf) up from an all-time low. (The bank was founded in the late 1600s, so that covers a long time.)

This doesn’t mark the start of a rate-hike cycle, like the one the US. The UK’s vote to leave the European Union last year put the central bank in a tight spot. Today’s rate hike—from 0.25% to 0.5%—does little more than reverse the cut in August 2016, in the immediate aftermath of the EU referendum that officials feared would lead to a recession. The economy has proven more resilient than feared, but has clearly weakened.

Now, the fear is that inflation, stoked by the pound’s sharp depreciation since the referendum, is running too far ahead of the central bank’s 2% target. In September, inflation reached 3%, the highest in five years. For months, bank officials have been weighing up whether rates should rise to try and bring inflation back down, or if monetary policy should keep supporting a shaky economy.

Today, seven of the monetary policy committee’s nine members voted for the hike. The two dissenters thought a hike wasn’t warranted yet, and the majority isn’t exactly bullish on the prospects for the British economy.

“The decision to leave the European Union is having a noticeable impact on the economic outlook,” the minutes of the rate-setting meeting said. “Uncertainties associated with Brexit are weighing on domestic activity, which has slowed even as global growth has risen.”

Officials unanimous agreement that any future hikes would be at a “gradual pace and to a limited extent,” suggesting that more hikes could be far off in the future. The uncertainty about how Brexit negotiations will play out led the bank to cite ”considerable risks” to its already rather meager outlook for the UK economy. The bank’s latest forecast suggested that its base rate will rise to just 1% by the end of 2020. This, and the downbeat economic assessment, led traders to dump the pound.

“Overall, the Bank may have hiked rates, but the outlook is cautious and downright weak regarding the strength of the UK economy,” said Kathleen Brooks, research director at City Index. “The BOE doesn’t look like it is going to follow the Fed and embark on a rate hiking cycle for many years yet.”

In the US, the Fed has raised rates four times since it started hiking in December 2015; it is expected to hike again in two months. The Bank of Canada has increased its benchmark rate twice this year as the Canadian economy started the year as the strongest in the G7. Meanwhile, the ECB recently put a plan in place to phase out its massive bond-buying program, as the euro zone’s economic recovery strengthens.

The UK, meanwhile, is basically back where it started immediately after the global financial crisis. The country’s base rate is back at 0.5%, where it was initially set in March 2009. Even as the employment rate is the highest on record, real wages have been declining since March. By 2018, the OECD expects the UK economy to be the slowest growing in the G7; three years ago it was the fastest. The UK’s productivity problem is much more severe than its developed market peers.

“What we’re doing is easing our foot off the accelerator,” the central bank’s governor, Mark Carney, said. “This is a modest adjustment.”