An amateur sleuth dug up at least one dead critic of net neutrality on the FCC website

James Harvey* wasn’t expecting to find a dead person. The 37-year-old was walking door to door, a list of names in hand, searching for former neighbors in his hometown. They were allegedly supporting the US Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) plan, announced in April, to undo its Obama-era policy of net neutrality (the principle that internet service providers shouldn’t make some sources of content easier to view than others).

James Harvey* wasn’t expecting to find a dead person. The 37-year-old was walking door to door, a list of names in hand, searching for former neighbors in his hometown. They were allegedly supporting the US Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) plan, announced in April, to undo its Obama-era policy of net neutrality (the principle that internet service providers shouldn’t make some sources of content easier to view than others).

Harvey had left his own comment on the FCC’s website in the summer supporting net neutrality, but what he found there had made him suspicious. The messages originating from Sharpsburg, Georgia (population 366), had all used a handful of templates like this:

In 2015, leftist billionaires and powerful Silicon Valley monopolies took the internet out of the hands of the people and placed it firmly under the thumb of the federal government, monopolies like Google and global billionaires like George Soros. Not surprisingly, today Obama’s new internet gatekeepers are censoring our viewpoints, banning our online activities and silencing dissenting voices….The FCC must stand up for a truly free and open internet by rolling back his cynical and self-serving internet takeover. The future of a free and open internet is at stake.

But it was not just the words. Harvey’s neighbors in Sharpsburg were never very political, yet 85 people, nearly a quarter of the town, had left comments. ”It was shocking to see the list of names,” he said.

So Harvey, a massage therapist near Atlanta, found himself spending nights off trying to track them down. First, he tried phoning, but the numbers led to dead ends. After a few weeks, he did what any resourceful citizen who felt lied to might do: He went to see for himself.

That’s how, on three days in late October, Harvey found himself walking down the streets of his hometown, a tiny hamlet carved out of the pine forests about 40 miles (64 km) outside Atlanta, looking for names of people who could tell him the truth. “It’s not normally something I usually do,” he said by phone. But he couldn’t shake the outrage at what he had seen on the FCC website.

Each afternoon, Harvey walked door-to-door asking people whose names were on the list whether they had commented about net neutrality (he chronicled his search in a Medium post on Oct 26). He managed to track down 10 or so people at home or whose family members called them while he was there. Of those, not one said they had left a comment with the FCC. One person’s address led to an abandoned storage shack belonging to a nearby family.

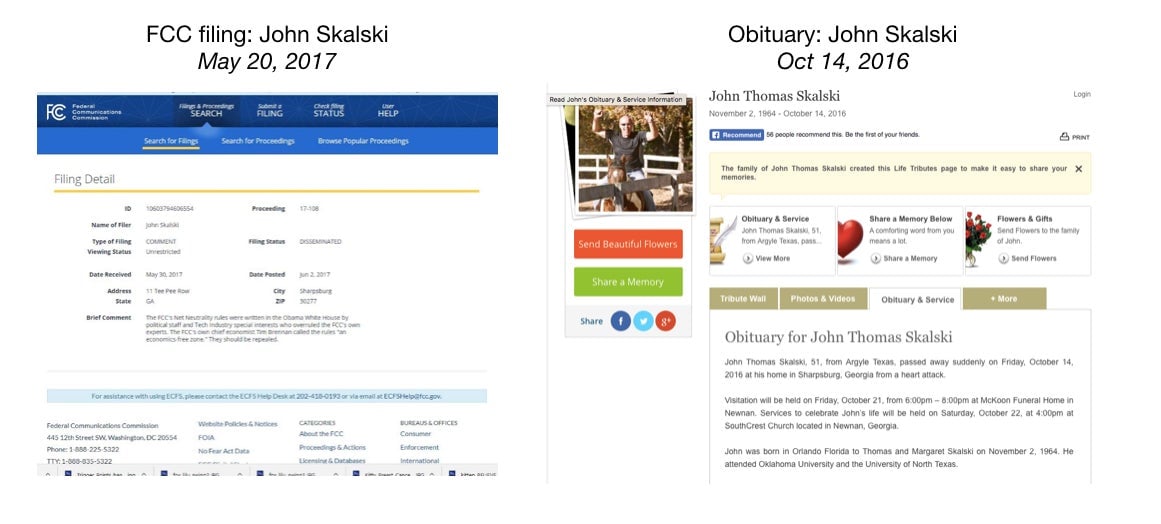

After Harvey knocked on one door to find John Thomas Skalski, a family member told him Skalski had passed away the previous year. The date of Skalski’s FCC comment was May 20, 2017. An obituary in The Newman Times-Herald says the 51-year-old died of a heart attack on October 14, 2016.

The FCC under Ajit Pai, a Donald Trump appointee, has not appeared over-zealous about policing potential fraud. There were already reports of apparent bot activity and of postings by dead people on the FCC pages back in May, not long after the agency had announced its intention of revisiting the net neutrality rules. When the comments period closed in August—by which time nearly 22 million comments had been submitted—a report (pdf) by an analytics company, Emprata, found that more than one third came from apparently fake email addresses. The agency did not react to those reports, and it did not answer Quartz’s requests for comment this week.

The FCC is now scheduled to reveal its specific proposal for rolling back net neutrality later this month—advocacy groups say around Thanksgiving. A vote will then be scheduled to officially change the policy.

Internet service providers that oppose net neutrality say they want more flexibility to adopt new business models (paywall), such as charge customers more to stream high-quality video services like Netflix. Opponents argue that net neutrality—which involved classifying the internet as a “common carrier,” letting the FCC regulate it like telecoms companies—is the only way to ensure it remains open to all. The FCC will make its decision, in part, on the public comments that it must sort and summarize.

Harvey says he pursued his investigation into fake comments to encourage others to do the same. “They’re faking grassroots,” he said. “If they can fake grassroots, and fake the numbers, they’re effectively taking away our democracy.”

Note: James Harvey is not his full name; he asked for his last name to be withheld for privacy reasons.