Stubbornly resistant to change, Japan is finally giving in for the sake of tourism

Kofu, Japan

Kofu, Japan

Yamanashi prefecture, located two hours west of Tokyo, is unlikely to surface on most must-see guides for people visiting Japan. And yet, tourists are swarming there.

In the last five years, the number of overnight foreign visitors to Yamanashi—Japan’s main fruit-growing and wine region, and one of the two prefectures that claims Mount Fuji—grew more than five times to 1.4 million by the end of 2016. That compares to a roughly fourfold increase for visitors to Japan overall in the same period, as tourism rebounded after a dip in 2011, the year of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

For many years, the perception that Japan was too expensive and difficult to navigate kept tourists away. Then the decrease in the yen’s value and Japan’s relaxation of visa requirements saw tourism grow to a record 24 million last year. Arrivals in 2017 passed that milestone last month. Now the government wants to more evenly distribute foreign visitors around the country, key to revitalizing small cities and rural parts of Japan as the population shrinks. Just three cities—Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo—account for 48% of foreign-tourist stays in Japan and 60% of tourist expenditure, according to a report (pdf) by consultancy McKinsey in 2016.

Yamanashi’s unusual success in joining Japan’s tourism boom owes much to its willingness to adapt to foreigners—something that isn’t easy for a country steeped in traditions and mind-bogglingly complex social protocol, much of it daunting to first-time visitors.

“Japanese people hate change,” said David Atkinson, an adviser to the Japan National Tourism Organization who has lived in the country for almost 30 years.

Relax: Your Japanese hosts are trying to chill out

Kofu, the sleepy capital of Yamanashi prefecture, is one example of an off-the-beaten-track city that is waking up to the potential of tourism.

Having sampled fruits from the area in their home countries, travelers are coming here from China, South Korea and increasingly Southeast Asia. Farms in Yamanashi that offer fruit-picking—grapes and persimmons in the fall, cherries and peaches in the summer—now offer guided services in Chinese.

Inside a brand-new tourist information center housed inside a minimalist, grey concrete block by the train station—and a stone’s throw from a statue commemorating Kofu’s most famous native, the warlord Takeda Shingen, who came close to uniting feudal Japan—visitors can peruse promotional literature in Indonesian and Thai. A tablet allows visitors to FaceTime with an operator in a selection of languages.

The efforts are part of a countrywide boom in private and public initiatives to use technology to overcome the language barrier to traveling easily in Japan, particularly as many websites and booking systems remain woefully out of date. For example, the national rail company only recently announced that it would launch an English-language app to allow foreigners to book bullet-train tickets, a uniquely befuddling experience for a non-Japanese speaker.

Helping foreign visitors also entails demystifying many of Japan’s complex rules and traditions, such how to properly stay in traditional inns, or ryokan. Many are operated by elderly proprietors who do not list their properties online, or at least not in foreign languages. Making a booking often requires a phone call, and many only accept cash.

Staying in a ryokan requires knowing where and when to wear slippers instead of shoes, and how to properly bathe in a hot spring, or onsen, a typical part of the inn experience. The relatively inaccessibility of ryokan may be one reason why, despite the explosion in tourist numbers, they are conspicuously missing out on Japan’s tourism boom. While occupancy rates at hotels have soared, the rate of growth for ryokan has lagged far behind.

Kinosaki in the Kansai region, the western part of Japan’s main island, is one hot-spring town that has made a concerted effort to simplify things for non-Japanese. The town this year won a government-sponsored award recognizing it for its hospitality efforts, with the number of overnight foreign guests in Kinosaki jumping from 1,118 in 2011 to about 40,000 last year.

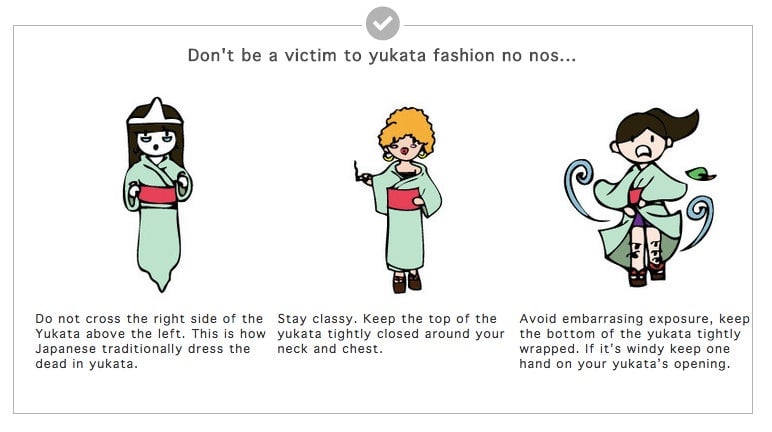

Makoto Koyama, a representative of the town’s tourism body, said that Kinosaki updated its website to provide detailed, graphic explanations of how to use a hot spring, for example, how and when to wear the yukata robe. He also highlighted an important selling point to foreigners—seven of its onsen allow people with tattoos, a break from common convention in Japan as tattoos are often seen as a mark of being connected to organized crime gangs, known as the yakuza.

Japan’s national tourism agency last year pleaded to onsen owners to relax their rules on banning people with tattoos from entering baths.

Kenji Sasamoto, the head of the Yumura Onsen Cooperative, an umbrella group of ryokan operators in Kofu, joked that “small tattoos are OK” for inked people who want to use a bath. Sasamoto, also the third-generation proprietor of Kofu’s Tokiwa Hotel, where two Japanese emperors have stayed, added: “We know they’re not yakuza.”

A flood of selfie sticks, and a ninja shortfall

As in places like Barcelona and Venice, the spike in tourists has inevitably given rise to complaints from local residents.

Tokyo locals are wary of foreigners (paywall) driving around the city in go-karts based on Nintendo’s Mario Kart game, which has resulted in a number of minor accidents—just this week, the transport ministry laid down new safety requirements (link in Japanese) for go-karts, including mandatory seat belts and tail lights. Kyoto residents, meanwhile, complain of being crowded out of their own city by hordes of selfie-stick-wielding tourists, and ambulances now broadcast messages (link in Japanese) in foreign languages to tell tourists to make way.

Airbnb has fought a particularly arduous battle to operate in Japan as homeowners grumble that out-of-towners don’t sort their recycling properly and make too much noise. The Japanese government this summer finally passed legislation to allow Airbnb to operate in Japan as a response to a shortage of accommodation—and Airbnb tied up in July with fintech venture Blue Lab to steer travelers to unusual lodgings, such as temples.

Prime minister Shinzo Abe has set a target of 40 million visitors a year by 2020, the year of the Tokyo Olympics—at the current rate, Japan is still nowhere near the top of the world’s most popular destinations.

If Abe’s wish came true, that figure would make Japan a more popular tourist destination than the UK, Mexico, and Thailand, but a lot of work is still to be done. In addition to overhauling outdated signs and websites, building more hotels, and making their hi-tech loos less intimidating (paywall), the country is also grappling with a severe labor shortage. That sometimes manifests in curious ways in the tourism sector, such as a shortfall in people working as ninjas (link in Japanese) to entertain foreign tourists.

Japan’s tourism industry has no choice but to confront the country’s demographic reality. A 2016 government policy paper (pdf) on tourism noted that while domestic tourism still contributes a large share to Japan’s travel industry, Japan’s population is “expected to keep decreasing.” Mizuho, a Japanese bank, predicts that (pdf) the number of domestic travelers will decrease by 4% between 2015 and 2020. The huge number of foreign visitors can more than offset that decline in some parts of Japan, said Mizuho, but in rural areas—where some 90% of hotel guests are Japanese—the loss in domestic visitors will be much harder to replenish.

“The domestic market is about to have its heart ripped out,” said Atkinson, the tourism adviser. “This is about saving Japan from ruin.”