The Republican tax plan saves companies and heirs $4 for every $1 it saves working Americans

If it wasn’t true before, it’s true now: Donald Trump is the anti-Ronald Reagan.

If it wasn’t true before, it’s true now: Donald Trump is the anti-Ronald Reagan.

The beloved Republican icon signed a major tax overhaul in 1986 that would become the touchstone of revenue levying legislation. Its main accomplishment was paying for individual tax cuts by raising taxes on business.

Trump is pushing for the opposite: a bill that would raise taxes on working Americans to pay for tax cuts on corporations and wealthy heirs. The Republican tax plan released on Nov. 2 includes $1 in cuts for working Americans for every $4 in cuts for corporations and heirs. And because those cuts to individuals aren’t equally distributed, some workers will end up paying more once the bill is enacted.

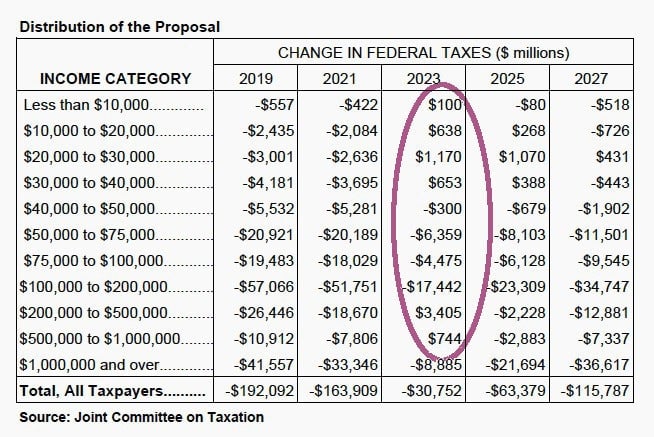

Check out the table below, released on Nov. 3 (pdf, p. 6) by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), the experts Congress relies on to assess tax proposals. It shows how much more or less tax the government would collect from different classes of earners under the new plan, compared to if the current tax regime were in force. For the first few years, all the numbers are negative—i.e., everybody is paying less tax. Then, in 2023:

Whoops! Suddenly the lowest-earning Americans, along with high-earning professionals, are being asked to pay more than they would under today’s tax system. (Not all will, but at least some.) In 2025, the better-off are back to saving again, but taxes on the working class are still higher. By 2027, when the proposal is in full effect, the balance has righted somewhat, but the wealthiest Americans are still disproportionately better off. And those in the $20,000-$30,000 income bracket—generally speaking, people who earn a living but really struggle to make ends meet—are taxed, on average, higher than before.

Why the big change in 2023? Most importantly, that is when a $300-per-person credit for dependents, put in to alleviate the effect of a higher tax rate on the lowest earners, expires. If Congress doesn’t re-up it—and the JCT doesn’t expect it will—taxes on workers will go up. All told, in the next decade, some working people won’t see their taxes go down at all, while the rich get the biggest cut:

What’s more, that chart underestimates how much money the very wealthiest will save. It doesn’t include the effect of ending the tax on inheritances $5.5 million and larger, which skews the bill even further toward the wealthy.

The analyses of this bill also reveal another interesting thing: If you take out that inheritance tax, the tax cuts for individuals are almost revenue-neutral. That is, reductions in rates are paid for by ending or shrinking tax deductions. This is why some people will end up paying more tax—the deductions saved them more money than the new lower tax rates will. These include people who’ve spent money on adopting a child, people who’ve borrowed more than $500,000 to buy a home, people with student loan debt, and even people with high medical expenses.

Most of these deductions do benefit wealthier Americans (who also tend to be the loudest complainers) so the political logic is that you can cut them out only if you also drop tax rates far enough. But delivering enough deduction cuts to balance out rate cuts has proven too hard, especially since Republicans aren’t willing to take on sacred cows like the tax deduction for health insurance, retirement savings plans that benefit the wealthy, or deferred foreign income… and want to abolish the inheritance tax, the biggest break to the wealthy of all.

In their original plan, Republicans had proposed a massive overhaul of corporate taxes that would arguably produce a more efficient system without huge losses in revenue. The idea was defeated by a coalition of deep-pocketed Republican donors with overseas business interests. In the current bill, businesses will receive a $1 trillion net tax cut, which is why there is so little wiggle-room to spread the pain among individuals. Indeed, the provisions that most benefit wealthy Americans make up the entire cost of the bill.